How the real cause of inflation has become a moving target

By shifting the blame for inflation from the pandemic to war in Ukraine and other causes, we miss the obvious culprit: the decreasing value of money itself.

In a nutshell

- Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine do not fully explain inflation

- Politicians have sought convenient targets to reallocate blame

- The underlying culprit is monetary and fiscal profligacy

When consumer price inflation first reared its ugly head in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis, the initial reaction of central bankers and politicians was to dismiss it, along with anyone expressing concern over it. As Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell put it, consumer price increases were merely “transitory” and nothing to be too worried about.

Once it became clear that it would not be such a short-lived problem after all, and that inflation was here to stay, much of the mainstream financial press echoed the narrative of political leaders who blamed it all on “supply chain issues.” According to that theory, prices were climbing due to the lingering effects of the lockdowns, business shutdowns and logistical disruptions to global trade during the pandemic. While not entirely implausible, this rationale failed to account for across-the-board price hikes. It was not just specific industries or particular categories of goods that were affected; everything was getting more expensive, and fast.

Another explanation blamed the Russian invasion of Ukraine – arguing that the war and subsequent sanctions against Moscow had wreaked havoc on energy markets, and as oil and gas got more expensive, everything else did too. This line of reasoning appears sound on the surface. The problem is that the consumer price increases preceded Russia’s invasion by months, so even though the war might have aggravated pressures in the energy market, it did not cause the larger global inflationary wave we experienced.

‘Greedflation’

As months passed with consumer price indexes (CPI) breaking records in many advanced economies, and as households were pushed into dire financial straits, public discontent made it imperative for politicians to find a scapegoat. “Capitalist greed” was a natural choice.

As Fortune reported, “Albert Edwards, a global strategist at the 159-year-old bank Societe Generale, released a blistering note on the phenomenon that has come to be called ‘greedflation.’ Corporations, particularly in developed economies like the U.S. and the UK, have used rising raw material costs amid the pandemic and the war in Ukraine as an ‘excuse’ to raise prices and expand profit margins to new heights.”

There is no doubt that individual companies took advantage of the inflation narrative to raise prices, and to levels much higher than what their actual cost increases could justify. However, they could only do so because of preexisting and widely recognized price increases – this “passing on the cost” excuse would never have worked in an environment that was not already perceived as inflationary. No group of bad actors, greedy CEOs or rogue corporate executives could possibly have managed to raise consumer prices across the board and throughout the entire world economy.

The core problem has never been about goods and services increasing in price; it is about money itself decreasing in value.

Even if some companies did try to squeeze out some extra profits by feigning or exaggerating increased costs and unjustifiably hiking their prices, the “greedflation” explanation still fails to account for the concomitant price increases across so many other commodities, companies, sectors, regions and nations. As with the Ukraine war theory, instances of corporate avarice might have exacerbated the problem, but they did not cause it.

The idea that corporate profiteering is the main inflation driver not only puts the cart before the horse, but it contradicts the prior explanations. If there were pandemic-related supply chain bottlenecks and energy market distortions caused by the Ukraine war, then it means the cost of raw materials did increase for producers, justifying higher prices.

Political appeal

As misleading as this theory is, it is undoubtedly politically attractive. United States President Joe Biden embraced it during a February meeting with union workers in Las Vegas ahead of Nevada’s Democratic primary, where he blamed corporate greed for high inflation. This narrative appears to have gained considerable traction. A poll by Navigator Research found that “since January of 2022, there has been a 15-point increase in the share who say ‘corporations being greedy’ is a ‘major cause’ of inflation (from 44 percent to 59 percent), with 17-point increases among independents (from 45 percent to 62 percent) and Democrats alike (from 55 percent to 72 percent).”

One can see how appealing such a populist concept can be, especially to those who have seen the real value of their paychecks shrink even as corporate profits and CEO bonuses explode. And it is not just politically expedient: it also helped sell the idea of the Global Minimum Tax on corporations to curb “excess” profits, which was further advanced this January after years of talks at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Facts & figures

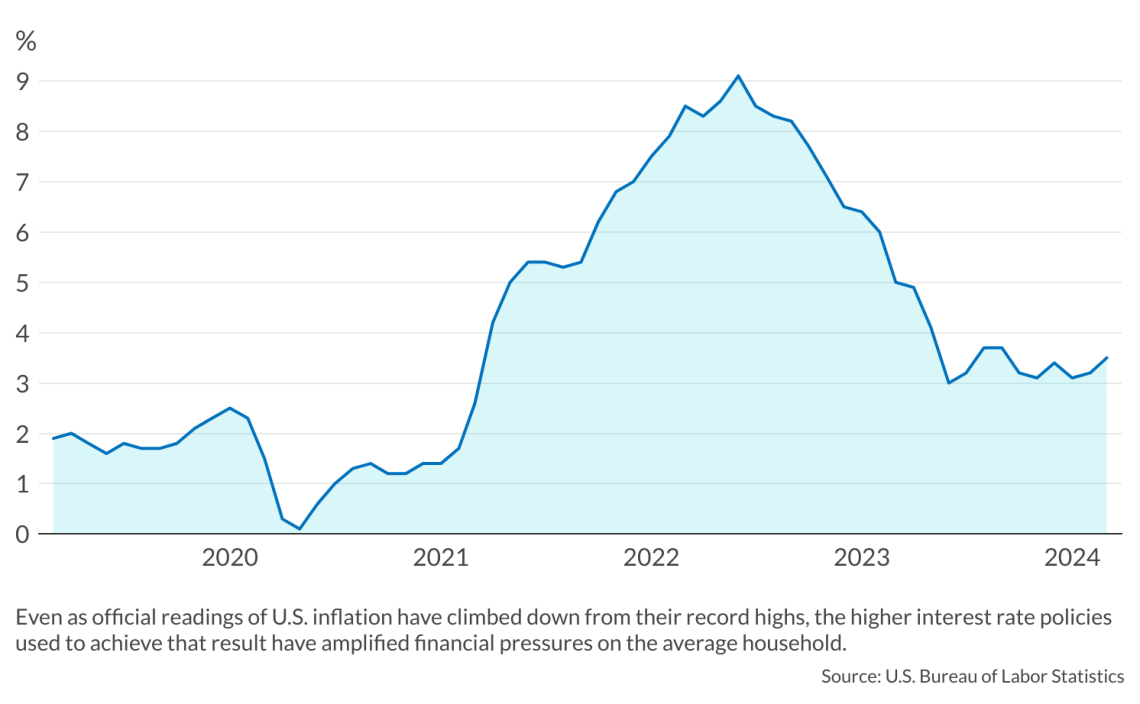

While blaming big corporations might have helped channel public anger toward supposedly evil capitalists and the rich, it did not do anything to solve the actual problem of inflation. In fact, the situation for most ordinary people became even more difficult. Even as official CPI readings have climbed down from their record highs in recent months, the higher interest rate policies used to achieve that result have amplified the financial pressures on the average household.

In the U.S., credit card balances increased by $50 billion, to a total of $1.13 trillion, during the last quarter of 2023, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, while interest rates on credit cards rose from an average of 14.6 percent to 21.5 percent since the Fed began its series of rate hikes. Overall household debt reached an unprecedented high of $17.3 trillion at the outset of 2024.

Blaming consumers

The pain caused by the tightening measures might have been worth it for many people if it had actually made a noticeable difference in lowering their grocery bills or other basic expenses. But despite the picture painted by official CPI readings, that did not happen (this is because these readings are unrepresentative of the real economy).

As public anger began to swell once again, a new theory was needed for why so many average citizens were struggling to afford both credit card payments and daily necessities. Having run out of villains to blame, the latest narrative sought to blame consumers themselves.

“Doom spending” is the newest concept deployed in the inflation debate and it effectively seeks to explain higher prices as a product of higher demand. Proponents say that higher demand stems from overwhelmed consumers (particularly Gen Z and millennials) who are crippled by anxiety and fears over economic uncertainty and the general state of the world. These people, the argument goes, seek relief through mindless spending, especially on luxury goods, big-ticket items and expensive traveling.

The evidence for this hypothesis is either anecdotal or based on poor-quality surveys. It also does not explain why this kind of consumer behavior has not been observed during previous eras of strife or challenges. Why did consumers not splurge on designer handbags to manage their stress after 9/11, during the eurozone crisis, or even at the height of the pandemic?

As Occam decreed, the simplest explanation is the right one. Put plainly, the core problem has never been about goods and services increasing in price; it is about money itself decreasing in value. The cause is also quite straightforward: chronic monetary and fiscal profligacy, also known as the “print and spend” doctrine embraced in most advanced economies.

More on monetary policy

- Public debt spells trouble for the U.S. economy

- How CPI calculations misrepresent real inflation

- Where have all the economists gone?

Scenarios

Given the level of creativity that has already been demonstrated by politicians, analysts and commentators who try to explain away inflation, it is hard to imagine what the next “theory” will look like. Whatever form it might take, it will certainly aim to distract from the real cause, namely monetary and fiscal recklessness. Given that 2024 is the biggest election year in history, with more than half of the world’s population heading to the polls, this could have very serious implications.

More likely: Continuing the blame game

One possible and likely way this distraction approach could backfire is by deepening sociopolitical divisions. If political leaders continue to blame individual groups, like the greedy rich or the mindless young, internal friction could intensify. Populism, whether coming from the political left or right, always has predictable results and they are deeply deleterious to social cohesion and economic progress. Encouraging the governed to blame their fellow citizens for their mistakes may be a great election strategy for policymakers, but it is a recipe for disaster for democratic stability.

Less likely: Confronting the problem

Another scenario, albeit less likely, is that more voters will realize the magnitude and severity of these attempts at misdirection, and seek change through the democratic process. While seemingly desirable in theory, the problem in practice is that for any future leader to acknowledge the true causes of inflation and take responsibility for them would be impracticable and politically suicidal. “Printing and spending” lies at the heart of our modern monetary and economic system, and it cannot be ripped out without risking further, and possibly even more serious, destabilization.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.