Insurance under pressure

The abrupt end of the cheap credit era has created winners and losers in the once-quiet insurance industry. Expect major shake-ups and, possibly, regulatory activity.

In a nutshell

- Parts of the insurance sector are reeling from the economic shocks of 2022

- The companies that dared to take advantage of cheap credit are strong now

- Others are struggling, inviting upheaval in that nook of the finance industry

The last several years have put insurance companies under pressure. The industry’s business models vary across the three distinct branches in which the companies operate: life insurance, non-life insurance and reinsurance. Life insurance offers financial products that enhance the beneficiary’s income welfare in the future, thanks to the insurer’s assistance. Contracts can also be arranged to include benefits to the insured, like a retirement scheme. In brief, insurers collect resources for a number of years, during which they accumulate liabilities that will be liquidated in the future.

By contrast, non-life insurance covers the insured against the losses related to risky events like poor health, job loss or accidents. In this case, the resources collected in a given year are used to cover the losses incurred by the insured in the same year. Finally, reinsurance characterizes companies that accept responsibility for at least some insurers’ liabilities. In other words, the insured pays the insurance company a policy, and the insurance company transfers the corresponding liability to a reinsurer.

Probability distributions and luck

Life insurance is profitable if the insurers’ asset managers can beat the promises made to the insured. Poor management and overly generous commitments to the insured mean losses. Non-life insurance covers a much shorter time horizon: its profitability depends on the ability to assess the probability distribution of a large set of events, on luck, on cost-cutting and on effective monitoring (administration and restraining fraud).

Interest-rate manipulation, price inflation and new waves of regulation have shaken the relatively quiet industry.

Profits and losses for the reinsurers are also about probability distributions and luck. Reinsurers prosper because the insurers may decide to expand their activities without running additional risks or choose to change their risk profiles – say – in the presence of new market conditions to which they are unwilling or unable to adapt rapidly enough. In this light, the fee paid to the reinsurer is the cost of being unable to react to change, buying time during the transition, to stop losses or secure profits.

During the past decade, interest-rate manipulation, price inflation and new waves of regulation have shaken the relatively quiet industry. The remaining part of this report looks at how these phenomena have affected life insurance and reinsurance and at what we can expect from them in the future.

Uncharted territory for life insurance

Central bankers’ interest-rate manipulation has deeply affected the life insurance segment. Under normal circumstances, insurers could offer a range of well-established and rather attractive contracts to the insured: the insured knew that their annual payments would turn into capital (liability for the insurers), the value of which would grow at a steady (low) rate, in exchange for protection against the ups and downs of the financial markets.

In some cases, insurers also offered protection against price inflation. Indeed, the past decade has been highly profitable for the insurance companies, which took chances and invested heavily in the stock markets, bonds or real estate. Ultra-low interest rates led to booming prices in all these areas, because of which risk-loving insurers saw their assets snowball while their liabilities rose at snail-pace rates. By contrast, those who thought the boom in asset prices would be short-lived and preferred to stay liquid lost money: over several years, their assets earned little or no interest while their liabilities kept rising.

Facts & figures

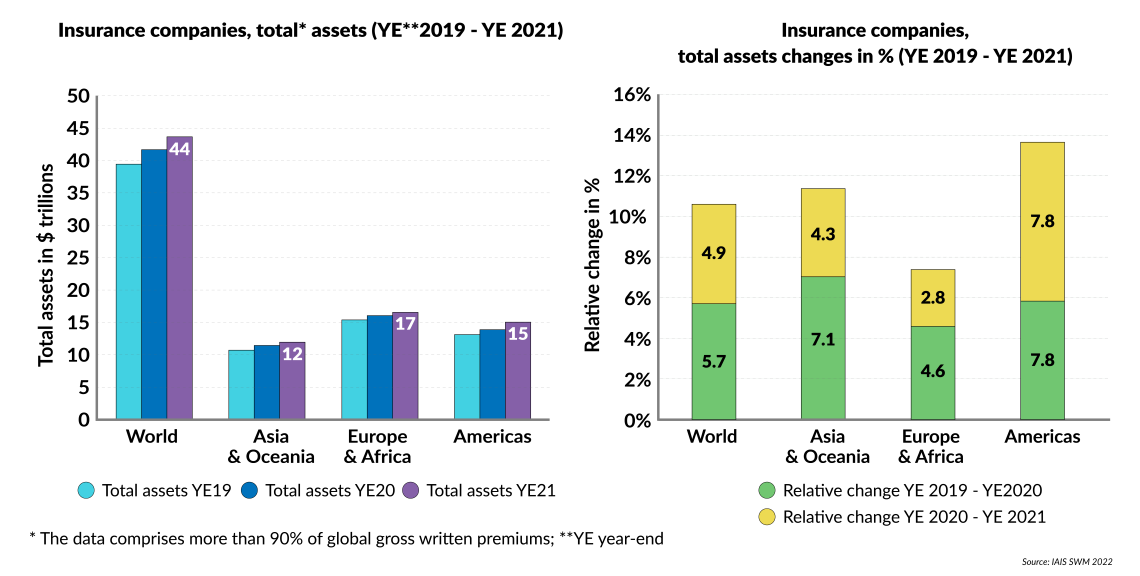

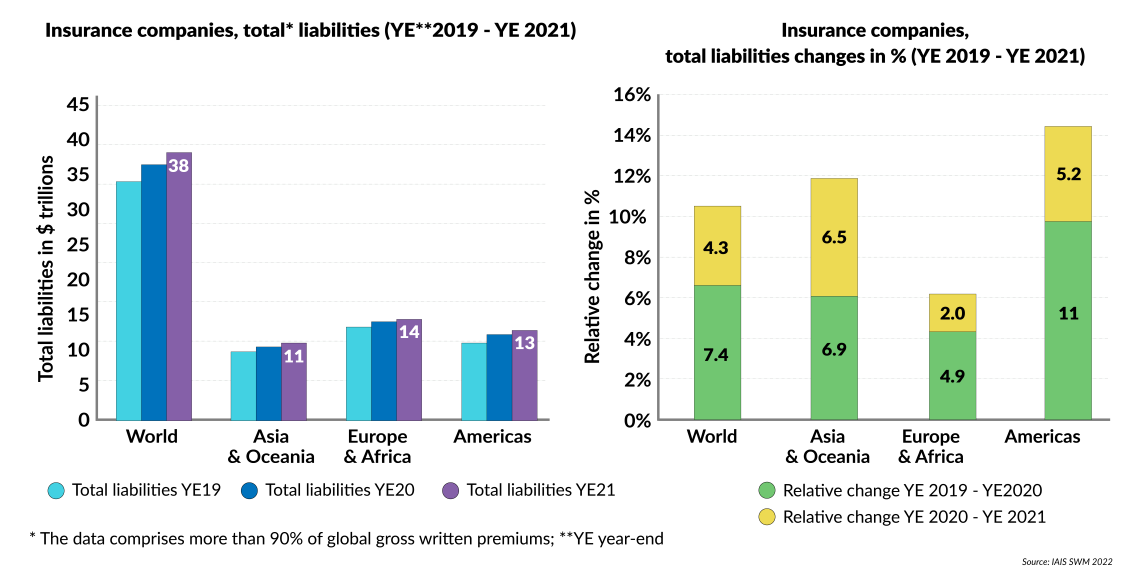

Insurance, global picture

In 2022, the financial boom went into reverse gear: nominal interest rates started rising, and part of the winners’ fat profits were eroded. Yet, their financial solidity has remained unaffected: their risk-taking had paid off, while the insured probably regretted having their assets frozen in low-yield insurance contracts. However, for some insurers, 2022 brought dramatic losses.

Problems in Europe’s financial industry

The political corruption of monetary policy

Think of those companies that had stayed put for a decade, had trusted central bankers’ statements about the ongoing era of ultra-low interest rates, speculated against higher rates and bought derivatives that promised the margins required to match their rising liabilities vis-a-vis the insured in a low-interest rate world. It turned out to be a bloodbath, especially for some United Kingdom companies eventually rescued by the country’s central bank.

On the other hand, the impact of inflation on the life insurance industry is unchartered territory. Three issues are going to be particularly relevant. First, insurers’ margins will, of course, be affected by their past commitments (e.g., inflation-indexed policies) and their ability to develop products that meet the new needs of prospective clients. Hence, asset managers can no longer sit back and relax by taking moderate risks and investing in safe and low-yield securities. The need to safeguard against inflation in a world that so recently featured low or even negative real interest rates will force financial experts to do their best. In many cases, their best will not be enough.

Mergers and acquisitions

The urge to improve performance in a fast-changing environment will increase competition, and some companies will face strong headwinds. Some, unable to adjust quickly enough, will first freeze their losses through reinsurance and then leave the market by trying to sell their life division to more effective actors (other insurers or banks). Undoubtedly, the risk-taking insurers of the past have the liquidity required to engage in ambitious mergers and acquisition operations, possibly in cooperation, or competing, with major banks.

Another issue, therefore, relates to the banking world, where the new features of the life insurance business open both opportunities and challenges. The opportunities regard the world of asset management, the weight of which has increased significantly in the banks’ balance sheets. A choice to further expand the role of life insurance liabilities will probably offer new challenges and opportunities for tomorrow’s bankers.

If insurance companies become larger, and banks further diversify their activities, who will need reinsurers?

Yet, one should not neglect that a big part of the insurance industry is healthy and highly liquid. At the same time, several banks are fragile and possibly vulnerable to the consequences of recession/stagnation: many questionable loans can quickly become losses.

Under such circumstances, and in contrast with the past, one can expect that a wave of acquisitions would see insurers in the role of the buyers, rather than sellers or partners. Or that successful insurers expand their current banking branches significantly and generate new ranges of business and organizational structures, thus putting the banks under further competitive pressure. Time (and regulation) will tell.

Uncertain need for reinsurance

As mentioned earlier, the reinsurance business may also move toward new scenarios. In general, reinsurance prospers in times of uncertainty, especially when the economic environment drives insurers away from their desired risk profiles. The next few years will probably present these same features: macro-uncertainties generated by undependable central bankers and unexpected risk profiles. But reinsurers will also have to consider the consequences of possible new waves of acquisitions. If these occur, it will be the reinsurers’ turn to respond to pressure. Put differently, if insurance companies become larger, and banks further diversify their activities, who will need reinsurers, and what kind of reinsurance would the market demand?

Cheap is over: Good and bad news for eurozone banks

The European Central Bank – independent and unaccountable?

Lastly, the monetary/financial authorities and regulators will play a crucial role, at least in two respects. The monetary authorities can influence the agents’ risk profiles. For example, why should one reinsure or moderate risk-taking if a friendly central banker promises to come to the rescue? Or why should one expand, and invest heavily in new organizational structures if regulators wave the anti-trust red flag, multiply the rules of compliance and, more generally, discourage competitive efforts and entrepreneurial innovation? And what would happen if regulators demanded that insurers be covered by powerful reinsurers, whom a central banker might, in turn, insure?

Scenarios

To sum up, the past decade has created winners and losers also in the insurance industry. The months ahead will be characterized by increasing competitive pressures, as happens when the winners try to consolidate, and the losers try to come back.

In theory, one should expect that these pressures benefit the insured and investors at large and will lead to leaner and more skilled managerial structures, lower fees and contracts tailored to suit the new needs. In practice – and this is the not so good part – times of change also present opportunities for the regulators. Indeed, their decisions may prove the primary source of uncertainty for all actors: banks, insurance companies and households. In contrast with the past, however, future households may pay dearly for their mistakes, as they no longer will be able to rely on the welfare state.