The Bank of England: How to crush a pro-growth vision

Why did the fiscal policies of UK Prime Minister Truss meet with such an uproar and why the BoE felt it necessary to move against them?

In a nutshell

- An attempt to restore the conditions for economic growth led to an outcry

- Reaction of the markets and the central bank doomed the UK government

- The BoE has followed in the steps of destructive ECB monetary policy

Elizabeth Truss became the United Kingdom’s prime minister in early September. Soon her reputation was in tatters, and she resigned under pressure on October 20. What went wrong and what opportunity did the Bank of England (BoE) forfeit in the drama?

In brief, soon after Ms. Truss took office, she and the Chancellor of the Exchequer Kwasi Kwarteng launched a free market set of measures focusing on tax cuts, deregulation and preventing some categories of social welfare benefits from keeping up with inflation. Civil servants’ salaries would also be cut severely in real terms.

Prime Minister Truss had been clear about her vision of what needed to be done weeks before her appointment. Yet, many commentators and parliament members were taken aback when she kept her word once at 10 Downing Street. As a result, her party let the new prime minister down, the BoE and the International Monetary Fund openly criticized her measures, financial markets were not happy and public opinion (including most of the press) was outraged.

Quick unfolding

Some days after financial markets reacted, the prime minister conceded that her proposal to cut by 5 percent the top tax rate on high incomes was politically inappropriate. The reversal could have given the new government a second chance, but it was probably too little and too late. Financial markets almost panicked and the BoE intervened and purchased plenty of British government bonds, a large portion of which was on the balance sheets of British commercial banks, pension funds and insurance companies. Thus, while the UK 10-year gilt yield had initially jumped from 3 percent (early September) to 4.6 percent (late September), it went back to 4 percent in early October and was still there when Ms. Truss resigned.

Her abrupt resignation made clear that she had little control over her party and did not adequately prepare the ground.

During the same period, the pound fell from $1.15 to $1.07 but recovered its earlier losses and was about $1.13 when the prime minister resigned. Oddly enough, many neglected to point out that interest rates had already been rising in previous months (they were below 1 percent in January 2022) and that the pound had been sinking all the time (from $1.35 in January 2022). One may suspect that Ms. Truss was a convenient scapegoat.

There is no doubt that September was a disastrous month for the new prime minister and that her decision to fire Chancellor Kwarteng was perceived as a sign of weakness. Indeed, it proved not enough for the leader to stay afloat, and her abrupt resignation made clear that she had little control over her party and did not adequately prepare the ground.

Put differently, Ms. Truss was brave and took her job seriously, but it turned out that many Tories had different views about her mission, and she underestimated how the BoE would react. As a result, the ambitious program has now been shelved.

Growth, not redistribution

The outline of the scenario that will emerge in the next few weeks depends on how the three major players – the new prime minister, the Conservative Party and the BoE – will move.

Ms. Truss was correct in arguing that growth is the best way out of a crisis, rather than money printing, inflation and redistribution. Although this sounds like a platitude, too many people seem to have forgotten that during the past two centuries world gross domestic product (GDP) per capita increased almost 14 times (and population more than seven times) thanks to technological breakthroughs and entrepreneurial efforts, not as a result of monetary manipulation, deficit spending and recovery and resilience plans.

Read more on the dilemmas of central banks:

Europe’s public debt: Analyzing the fear factor

Indeed, such growth has made everybody better off, including the poor, and has put the world in a much better position to confront crises. Yet, the new chancellor of the exchequer, Jeremy Hunt, has backtracked on Ms. Truss’ battle plan. His basic message has been that he would operate together with the BoE to ensure stability, i.e., business as usual until Downing Street has a new tenant.

It seems evident that the Conservative Party is unwilling to stand up against the BoE and the financial community – banks, insurance companies, investment and pension funds. However, it is far from evident that this will be enough to avert disaster for the ruling Tories in the next elections.

Facts & figures

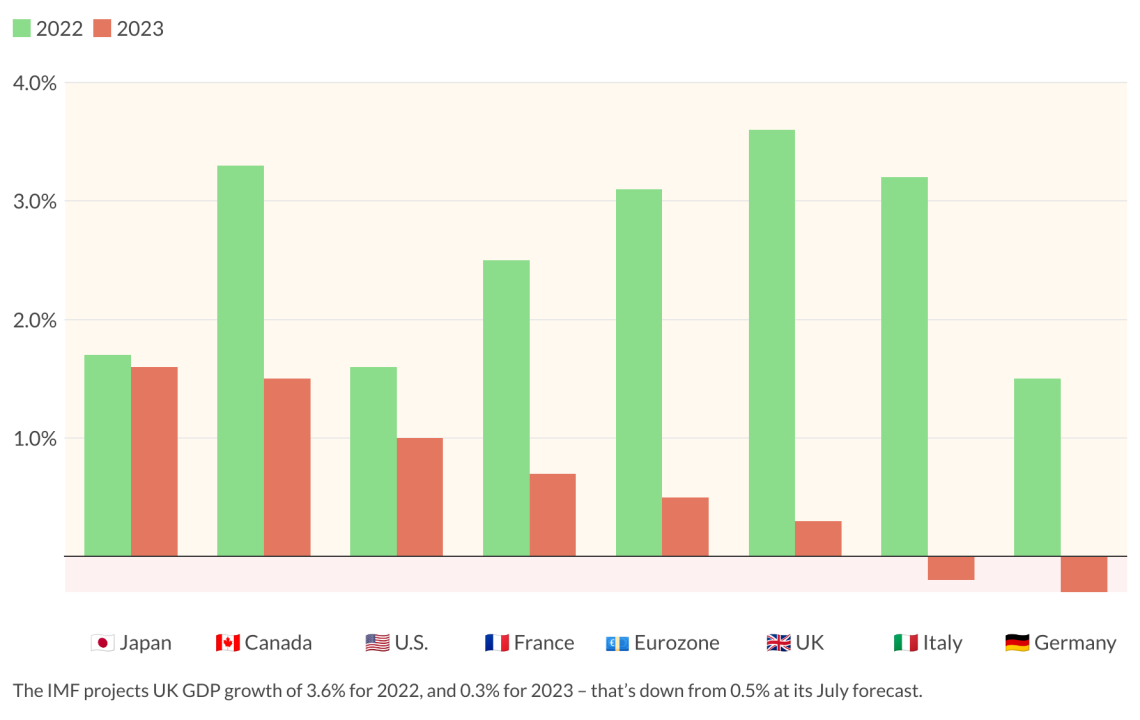

In late October, polls on voting intentions showed a 30 percentage-point lead for the opposition Labour Party. The British economy is in relatively good shape. Although its GDP is still (marginally) below its pre-Covid level and has stopped growing, the IMF predicts that during 2022 the country’s growth will be above 3 percent (the data for the euro area is 2.6 percent). Moreover, the rate of unemployment is about 3.5 percent (6 percent in the EU), and the debt/GDP ratio (96 percent) is not much above the EU’s (88 percent). Yet, the prospects for 2023 are not exciting: 0.5 percent GDP growth for the UK (and 1.2 percent for the eurozone). The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is even more pessimistic.

High inflation will not make things easier: the rise in consumer prices on an annual basis is currently around 10 percent, and expectations for 2023 are above 6 percent. Whoever is in power will probably be blamed, regardless of their policymaking.

Scenarios

Will the new government be able to make progress and perhaps appreciate at least part of Ms. Truss’s vision? Three significant hurdles stay in the way of free-market reforms.

Time lag

One boils down to a delay in time. Structural reform to enhance economic growth does not produce immediate results. An economic environment that encourages entrepreneurs to engage in new ventures and expand production capacity is essential. However, investors and entrepreneurs need time to find the new context credible and not likely to change again in a couple of years – especially if the Tories give up their identity as free-market advocates and the polls show that the Labour Party will carry the day.

Expenditure cuts

Secondly, Ms. Truss’s experience has underscored that significant cuts in public expenditure are essential to prevent the budget deficit from intolerably increasing before growth expands the tax base and generates adequate revenues. The deficit was almost 15 percent of GDP in 2020/2021; before the latest leadership crisis, it was projected to drop to 6 percent in 2021/2022.

The BoE

The third set of problems regards the role of the BoE, which is understandably nervous about inflation but also about the fragile condition of the vital financial actors. When forced to choose between monetary stability (inflation) and financial stability (avoiding heavy losses for banks and pension funds), the bank goes for the latter and avoids significant reforms.

In the end, one fears that 10 Downing Street might become a branch of Threadneedle Street. The BoE’s tolerance for high taxation and fascination with market manipulation and regulation will not make banks and pension funds healthier. The inflationary problem may worsen: expectations about the future of price rises can quickly deteriorate, interest rates rise faster than anticipated and volatility intensify. As a result, growth will be stifled; pressure groups will be more and more active in demanding subsidies and the budget deficit will come under renewed pressure.

The irony is that BoE Governor Andrew Bailey will likely emerge as the white knight and the new prime minister as his political executive. Admittedly, Ms. Truss was an imperfect copy of Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s ‘‘Iron Lady’’ prime minister (1979-1990). Having refused to join the eurozone, the UK had an excellent opportunity to keep inflation at bay from the beginning. By following in the footsteps of the European Central Bank leaders Mario Draghi and Christine Lagarde, however, the BoE governors forfeited that opportunity, and Prime Minister Truss did not have the political power to undo the damage and defuse the panic.

That is hardly surprising: confronting the BoE in the 2020s is tougher than lashing the trade unions, as the Iron Lady did in the 1970s. Those following Ms. Truss did not even give it a try.