Separating propaganda from reality in Iran’s economy

While Tehran has made diplomatic inroads to ease isolation from the West, domestic troubles will not go away for the mullahs in charge.

In a nutshell

- Despite recent economic and diplomatic successes, deep troubles remain

- China is taking advantage of Iran’s weak position with one-sided trade deals

- Discontent with the theocratic regime increases a desire for secularism

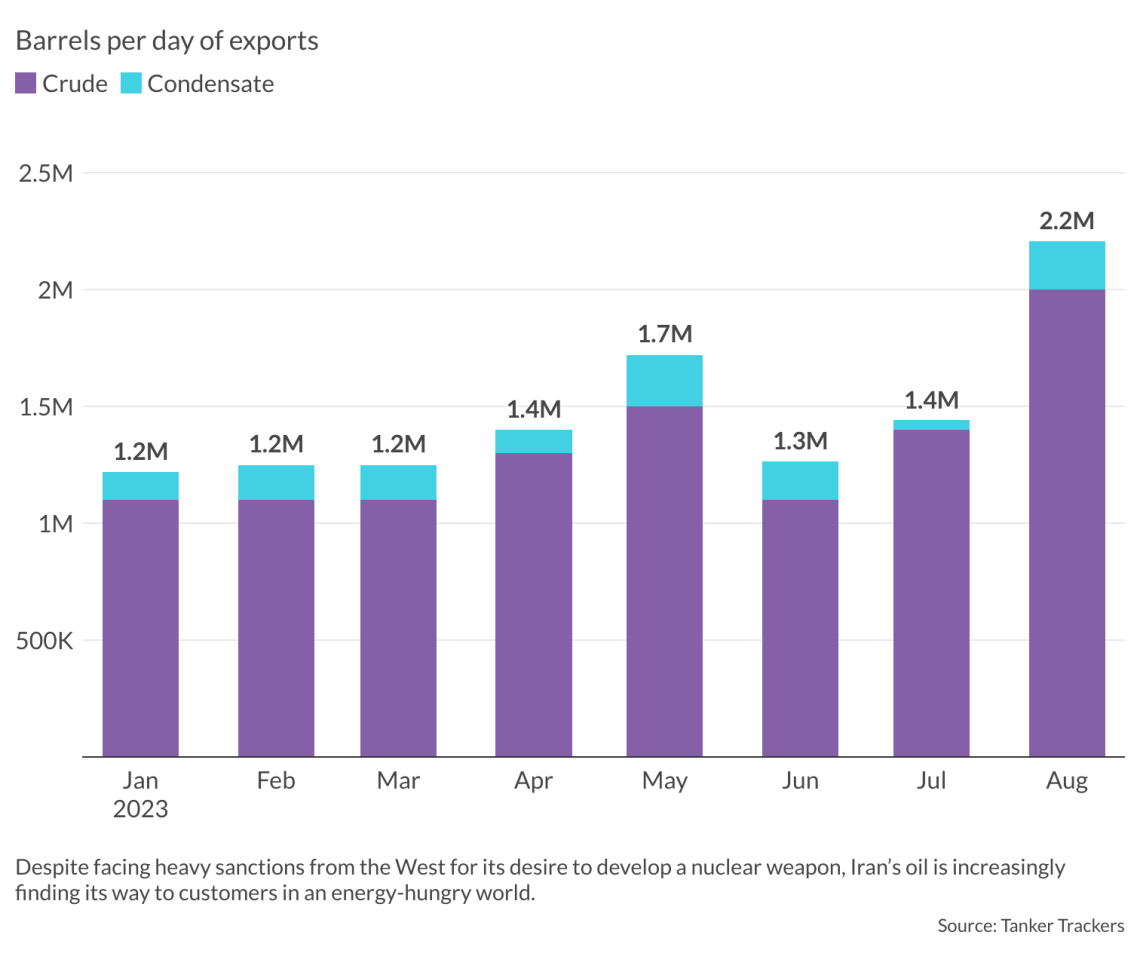

Officially, all is well in the Middle Eastern nation of 88 million people. Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi is touting recent economic indicators as bright: oil brought in $54 billion in 2022 while overall exports hit $73 billion that year. Iran joined the nine-member Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), which also includes four Central Asian countries, China, India, Pakistan and Russia. Tehran has also been invited to join the enlarged BRICS group in 2024.

Joining the select club of emerging economies is not only a finger in the eye of the West, but it also shows Iranian diplomatic skill in combating economic isolation and promoting its development. After many lean years, the World Bank believes the country has “started to recover.” Iranian households have never put so much petrol in their cars to enjoy mobility. Direct investment in the construction sector is meeting the demand of the Iranian middle class for new housing on the outskirts of major cities.

Although consumerism is the antithesis of the regime’s values, shopping malls are packed. A consumer society is blatantly on display, from booming computer shops to garments dominated by Chinese imports. Iranians are making their demands known. In a move that would have been unthinkable 20 years ago, they are banding together in associations. They demand regular rice supplies to local supermarkets and an end to sudden and unexplained price rises for everyday items such as cooking oil and soap.

But all is not well, even though economists expect modest growth and an increase in nominal gross domestic product (GDP) close to $400 billion in 2023.

Demonstrations are taking place in major cities to protest food inflation and the weakness of the national currency. Red meat is more expensive than in any other country in the region. Iran lacks the resources to support its beef industry. As a result, it has had to resort to importing meat from Kenya. Anomalies affect the automotive sector despite its promising future. Inflation is such that a year after being bought, a car is resold on the secondhand market at a price higher than its original value. The massive injection of cash into the local economy, described by the Iranian press as a “waste of paper,” has not prevented poverty from rising. The concept of absolute poverty has emerged. Begging in big cities is routine.

Since President Raisi took office in 2021, Iran has expanded its activities abroad. It circumvents Western sanctions by focusing on such neighbors as Pakistan, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. To the west, in the countries of the axis of resistance (Iraq, Syria and Lebanon), Tehran is trying to establish a Pax Irania that will deepen its strategic depth and, it hopes, generate lucrative business. To the south, the resumption of diplomatic relations with Riyadh has an economic component. The question is one of trust. Beyond statements of political intent, is there a genuine willingness to cooperate?

More by Pierre Boussel

Middle East groups learn lessons from the Ukraine War

Lebanon’s presidential standstill

ISIS keeps dwindling in Syria

Neither East nor West

To break out of its isolation, Tehran is increasing the number of bilateral agreements based on political convergence and economic ambitions. Its strategic partnership with China, with an advertised value of $400 billion over 25 years, was signed by the two countries’ foreign ministers in 2021, but the agreement’s final form has not been officially announced. Such initiatives are supposed to demonstrate Iran’s ability to play on geopolitical antagonisms – in this case the Sino-American dispute – to its benefit.

But President Raisi is impatient with Chinese promises of investment in the energy and agricultural sectors. Political declarations of good intentions have been replaced by rationality, which brings its share of bad news. Sinopec, the Chinese energy and chemicals giant, has quietly canceled its contract to develop the Yadavaran onshore oil field in southwest Iran, apparently disappointed by projected returns.

Some Chinese policies are irritating Tehran. Beijing pays about 10 percent less for Iranian crude than for Russian oil – which is 30 percent under the world market price. Payments are made in nonconvertible yuan, a currency that can only be used to buy Chinese products.

Consumers have little choice but to buy “made in China” products such as textiles, kitchen appliances, sports equipment, toys and cars, both privately and commercially. And China uses its dominant position to charge exorbitant prices: some Chinese cars sell for three times as much in Iran as in the Gulf, even though purchasing power is much higher there.

President Raisi hoped to benefit from China’s economic power and become a full partner, among others, in the field of artificial intelligence. Iran wants to be part of this dynamic of progress that fascinates its young people. Long left behind, it is convinced it has a card to play. Training centers are churning out a new generation of data scientists and programmers. But while Tehran wants to work on innovative projects on an equal footing with the Chinese, Beijing does not. It manages its own affairs, especially in Afghanistan, where Tehran has interests. Unlike its ally Moscow, China acts tough and uncompromising regarding business. It is aware of Iran’s weak position and urgent need for foreign capital to keep its economy afloat.

Relations with the Kremlin are more balanced. Although Tehran has always been wary of Russian interventionism, the countries are united as among the most heavily sanctioned in the world. When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Moscow and Iran linked their banking networks to compensate for the SWIFT cutoff. They have set a target of $10 billion in annual trade.

While the Russians are signing big contracts, they do not understand the Iranian market for goods and services. Conversely, the Iranian business community is not sufficiently familiar with the Russian market to create a genuine dynamic. Kambiz Mirkarimi, vice president of the Iran-Russia Joint Chamber of Commerce, believes that removing customs barriers and establishing a free trade market would turn political declarations of good intentions into actual contracts.

In its foreign policy, revolutionary Iran sought to place the “neither East nor West” credo of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the 1979 revolution, above the vicissitudes of the world. The survival instinct of the Iranian economy has decided otherwise: Tehran is now forced to align itself with the powers of the East.

Resilience amid hardship

The resilience of Iran’s middle class has been the subject of many studies.

The latest wave of protests, sparked by the tragic death of Jina Mahsa Amini at the hands of the Gasht-e Ershad (morality police) in 2022, included several socioeconomic demands, such as reducing inflation. Although the state subsidizes basic foodstuffs to the tune of 5 percent of GDP, it has been unable to stem inflationary pressures and stop the collapse of the national currency. One United States dollar is exchanged for 42,000 Iranian rials on the open market.

Living standards are eroding, exacerbated by administrative shortcomings on display during the Covid-19 pandemic. Illicitly imported medical equipment is a scourge, particularly in the imaging sector. Machines are sold without after-sales service. The scrappy industriousness in which the Iranians have excelled after decades of sanctions is reaching its limits. Drug shortages have become commonplace. According to one Iranian newspaper, 700 essential medicines are in short supply. As a result, smuggling is flourishing. Around 20 percent of the medicines consumed in Iran pass through networks of drug traffickers.

Daily life in Iran is also hit hard by natural elements. Flooding has risen as the soil, hardened by drought, can no longer absorb rainwater. In hot regions such as Sistan-Baluchestan, sand and dust make the water undrinkable and destroy crops on small family farms. The poorest families are forced to abandon their plots of land and crowd into the suburbs of major cities, where they survive on odd jobs. Iran has been unable to solve an age-old problem: the deep divide between the countryside, often poor and conservative, and the urban centers, open to the outside world and entrepreneurial. There is a vast gulf between the start-up founders of Tehran and Iran’s agricultural sector, which is often family-run, poorly mechanized and lagging behind the challenges of sustainable agriculture.

Food and work are the priorities of the Iranian people. Unemployment is a constant threat, a sword of Damocles over an economic recovery that is fragile and uncertain. To preserve employment, the government no longer authorizes closing production units. Its impact will be difficult to quantify given the reluctance of Tehran to make official figures verifiable.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

Less likely: Iran pulls itself out of the hole

In the first, less likely scenario, the Iranian economy confirms hints of relative improvement in its leading indicators. It benefits from the reorganization of international relations following Russia’s war in Ukraine and becomes a cog in the new centrality of Asia. With Tehran stabilizing its nuclear program at the “threshold” level, or six months away from building a bomb, the U.S. will maintain its sanctions against the regime under the 2011 American law (CISADA). But the sanctions are not preventing Tehran from gradually recovering from its long economic doldrums.

More likely: Iran’s struggles will continue

In the second, more likely scenario, Iran continues its rapprochement with Moscow, and its difficulties with China, which refuses to establish a balanced relationship, remain. The regime struggles to stabilize the economy, but political anger lingers. New waves of demonstrations break out. Secularism rises, confirming the deep divide between the countryside, historically loyal to the mullahs, and the urban centers eager for political change that would enable them to achieve their dream: freedom to be and think.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.