Japan accelerates and expands its defense preparations

For seven decades, Japan was comfortably ensconced in its stable geopolitical framework. With the rise of China and new responses from the United States, this framework is evolving. Japan is called upon to enhance its military capabilities and strengthen its security – not only within its territory but also far beyond in the Indo-Pacific region.

In a nutshell

- Japan faces regional crises and uncertainty about U.S. intentions which necessitate a new approach to its security

- Tokyo’s political stability and good relations with Washington are rare bright spots in the Indo-Pacific region

- Japan is close to bending constitutional restrictions to build up its blue-water navy and the air force.

For seven decades after World War II, Japan was comfortably ensconced in a geopolitical framework that seemed both stable and predictable. With the rise of China and, more recently, new responses from the United States to economic and geopolitical challenges, this framework is evolving. More than ever in the postwar era, Japan is called upon to enhance its military capabilities and strengthen its security – not only within its territory and territorial waters, but far beyond in the Indo-Pacific region.

Multiple crisis points

At present, Tokyo faces several crisis points. Developments on the Korean Peninsula have become very volatile. On the one hand, Tokyo is in the dark about what Washington, or, more precisely, U.S. President Donald Trump, plans as the next move in the game with North Korea. Most worrying to the Japanese is the fact that Mr. Trump is unwilling to punish Pyongyang for flaunting the United Nations’ trade embargos. He also makes light of the North Koreans’ missile tests and, most likely, closes his eyes to advances in their nuclear weapons program.

These weapon systems may not pose an immediate threat to the security of the U.S., but they indeed threaten South Korea and Japan, whose territories are well within reach of the ballistic missiles that are being finessed by North Korea.

Then there is the severe and deepening discord between Seoul and Tokyo. In their latest move, the South Koreans have stopped security cooperation with Japan – which must be of grave concern for the entire region, as it may limit its capacity for on-time and effective responses to Pyongyang’s military moves. Emotions between Japan and South Korea have reached such heights that even Beijing has seen the need to admonish the two neighbors to calm down.

There is also pressure from President Trump, who demands that U.S. allies do more for their defense.

Tokyo has professed its deep concern over Beijing’s militarization of the South China Sea but, up till now, has remained on the sidelines, at least militarily, arguing that its constitution does not allow for the deployment of Japanese military forces beyond its territory. As the Southeast Asian nations also seem unwilling to – or incapable of – taking on the Chinese, the U.S. stands as the sole guarantor of freedom of navigation in this crucial part of the Pacific Ocean.

Most recently, another security worry has alarmed Japan: the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz in particular. Again, important supply chains pass through these seas. Japan’s economy, which imports all the fossil fuels it uses, would be profoundly affected by a disruption of shipping there. In the background, there is also pressure from President Trump, who calls on the U.S. allies to do more for their national defense.

Facts & figures

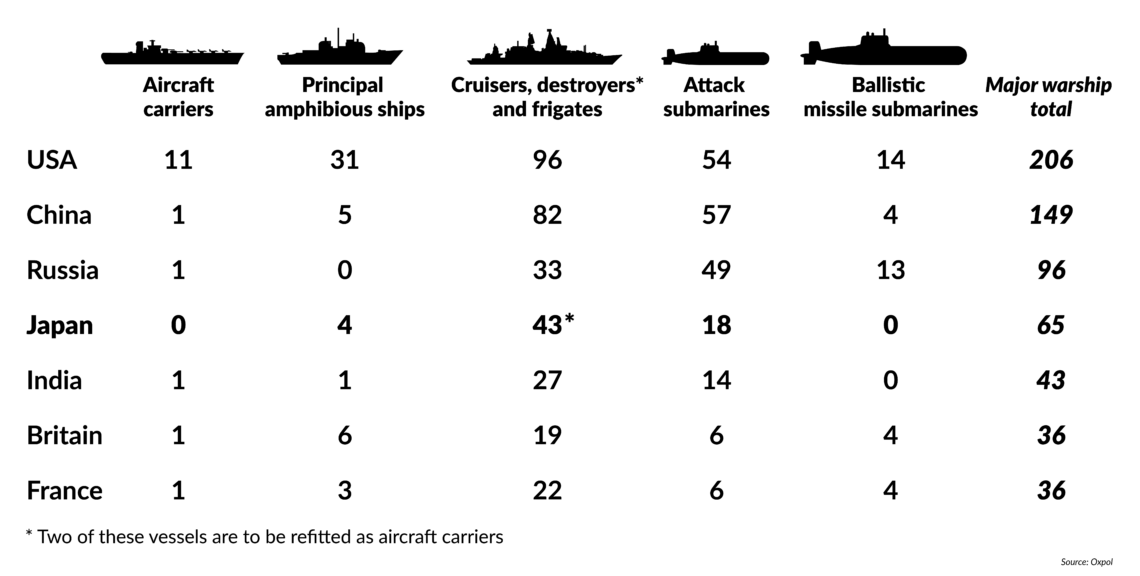

The world’s fifth-largest naval force

● Officially, Japan’s Maritime Self Defense Force (MSDF) is not a military force; its personnel are civil servants. In reality, however, Japan has built, largely under the radar, a naval force that is considered the world’s fifth strongest, technically on the cutting edge and professionally manned

● This force features a total of 114 ships and 45,800 personnel. Its core is the fleet of 43 destroyers, cruisers and frigates serving to keep the sea-lanes to and from Japan open. More recently, the MSDF’s Aegis destroyers have also been tasked with protecting Japan from incoming North Korean ballistic missiles

● The MSDF’s three so-called “helicopter destroyers,” twice as large as the average destroyer, are aircraft carriers in all but name. Aside from transport and attack helicopters, they will soon embark F-35B fighter bombers. Each warship also can carry a battalion’s worth of marines

● The force also features a growing amphibious capability. Its three 9,000-ton, helicopter- and hovercraft-equipped tank landing ships can each move 300 troops and a dozen heavy vehicles

● Its submarine force of 18 vessels, planned to expand to 22, is counted among the very best in the world. The MSDF makes sure its submarines are young; they serve no longer than two decades. The latest addition to the fleet, the Soryu-class boats with advanced propulsion systems, can remain submerged longer than other conventional submarines

Source: The National Interest

New hardware

Security experts who worry about stability in the Far East perceive the Tokyo-Washington relations as one of the region’s few bright spots, given the strength of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government and his clear commitment to enhancing Japan’s defenses. The strategy materializes with military hardware purchases and new political approaches that reach beyond a timid and reluctant interpretation of Article 9 in the Japanese constitution. The article, in principle, denies Japan the right to wage war. Significantly, this constitution, never altered since its promulgation in 1947, was written by the U.S., at the time the power occupying Japan.

Prime Minister Abe enjoys good working relations with President Trump, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the leaders of Australia’s conservative government. He stands for stability as Japan’s longest-serving prime minister after World War II. Before Mr. Abe, Japanese prime ministers hardly stayed in office for more than two years. The current leader of Japan also has a clear vision about the country’s need to enhance its military power to a point where it can stand up to China and defend its territory.

Facts & figures

Japan has returned to the rank of top maritime powers

On the hardware side of this program, Japan emphasizes expanding its defense capabilities in the air and on the seas. It plans to procure an impressive fleet of 147 fifth-generation Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighters – 42 of which are to be the short takeoff and vertical landing B models capable of operating from two of the Japanese navy’s three largest warships, the Izumo-class helicopter destroyers, soon to be refitted into compact aircraft carriers. This project is a game-changer, as Japan could return to operating a blue-water navy for the first time since World War II. Also, it is making an effort to enhance its amphibious forces.

China has already protested and accused Tokyo of stimulating an arms race. Obviously, Beijing is aware that aside from the U.S., it is India and Japan that, in the future, may be called upon to contain the Chinese capabilities on the high seas.

For now, Japan’s massive purchase of U.S.-made warplanes may at least take some steam off President Trump’s charge that allies in Southeast Asia are not paying enough for U.S. military presence. Although Japan foots substantial bills for the upkeep of the American bases on the Japanese archipelago, its expenditure on defense amounts to a mere 1 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP), making it an open target for Mr. Trump’s criticism. (Tokyo argues, of course, that the U.S. profit from their military presence in Japan for their own forward defense; it would not be possible to deploy the U.S. troops currently stationed in Japan to the base on Guam.)

New strategies

Not long ago, Asia was compartmentalized in terms of geopolitics. There was the Pacific, where cooperation among the rim states had some institutional bases in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). The planned follow-up – the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP, which was supposed to add to this framework – was frustrated as President Trump withdrew from it as one of his first acts in office.

China’s rise has substantially altered the perception of regions in Asia: today, there is the Indo-Pacific region.

The Indian Ocean was an altogether different region, for a long time of little interest to Japan and other Asian actors. Furthermore, since the Indian Ocean is rimmed mostly by developing countries with low participation in trade and even less geopolitical influence, it did not materialize as a coherent region. All this has changed in most recent times. First of all, there are the three strategic entry points into and out of the Indian Ocean: the Straits of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait leading into the Red Sea. These have become major crisis spots in the second millennium.

It is China’s rise that has substantially altered the perception of regions in Asia. Today, all talk of the Indo-Pacific region. The world is aware that geopolitical tensions and cohesion processes have turned the Indo-Pacific into an area of common threats and crises, which, in case of a war, might easily inflame each other. The most prominent area where such changes took place is the South China Sea, which spans two crucial bodies of water, the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean.

In the past few years, the navies of Japan, India and Australia have enhanced their cooperation. Japanese vessels have participated in joint naval exercises. Tokyo adheres to what is called a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy” (FOIP), aware that in future open conflicts, Japan will be called by the U.S. to contribute its share in defense of open seas.

Prime Minister Abe believes there is enough room for Japan to enhance its capabilities with Article 9 in place.

John Bolton, until recently the national security advisor to President Trump, was a relentless promoter of deploying U.S. new intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBM) in Asia, notably in Japan. His campaigning resulted in loud protests by the Chinese and caused U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper to declare that the U.S. was not asking for such a deployment as of now. However, there is little doubt that this significant enhancement of U.S. military power in Asia is to take place in the foreseeable future.

Scenarios

In the light of numerous uncertainties affecting East Asia, it is comforting to see the political stability in Japan. For the coming two years, and maybe even beyond, Prime Minister Abe will be firmly in the saddle. Most recently, he has demonstrated that within the Liberal Democratic Party and his government, Shinzo Abe rules supreme.

Also, the prime minister has shown remarkable consistency in his efforts to strengthen Japan’s security and lead his country to more engagement in international strategic affairs. To date, however, he has not been able to achieve his stated goal of abolishing Article 9 of the constitution. The change would require not only a qualified majority in Parliament but also approval in a popular referendum. It is questionable whether these obstacles can be overcome soon.

On the other hand, looking at the most likely scenario for the coming years, we can be sure that Japan, within its region and beyond, in South East Asia and the Indian Ocean, will strengthen its strategic presence.

Prime Minister Abe believes there is enough room for Japan to enhance its operational capabilities even with Article 9 still in place. Most importantly, Tokyo will increase its logistical engagement in operations beyond its borders. Beijing’s reaction is an indication of Chinese concerns about the expanded capabilities of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force.

Japan has a long experience in naval warfare, much more extensive than its Chinese and South Korean neighbors. In the case of blue-water deployments, typical for aircraft carrier groups, maritime tradition and experience count for plenty.

Finally, in the past, Tokyo’s defense strategies have focused on openly or potentially inimical powers. Now, the defense scenario has to account for concerns about the reliability of the U.S. support in case of a crisis. Small wonder that Tokyo has been shaken by Washington’s approach to North Korea and by statements from President Trump that indicate a weakening of the American commitment to assist Japan in the case of war. Ominously, Mr. Trump said that the “unfair” defense treaty with Japan, which places a lesser obligation on Japan to defend the U.S. than vice versa, needs to be revised. He did not threaten to withdraw from the treaty, which both sides call a linchpin of stability in Asia-Pacific, but deemed it too burdensome for the U.S.