Once again, Pacific security is Japan’s priority

As Tokyo pursues vital regional geopolitical interests, it must tread cautiously because of its legacy.

In a nutshell

- The tragic history of the 20th century still weighs heavily on the Far East

- Japan’s new security policy responds to the aggressive moves by China

- Tokyo’s aid focuses on maritime, economic security and other interests

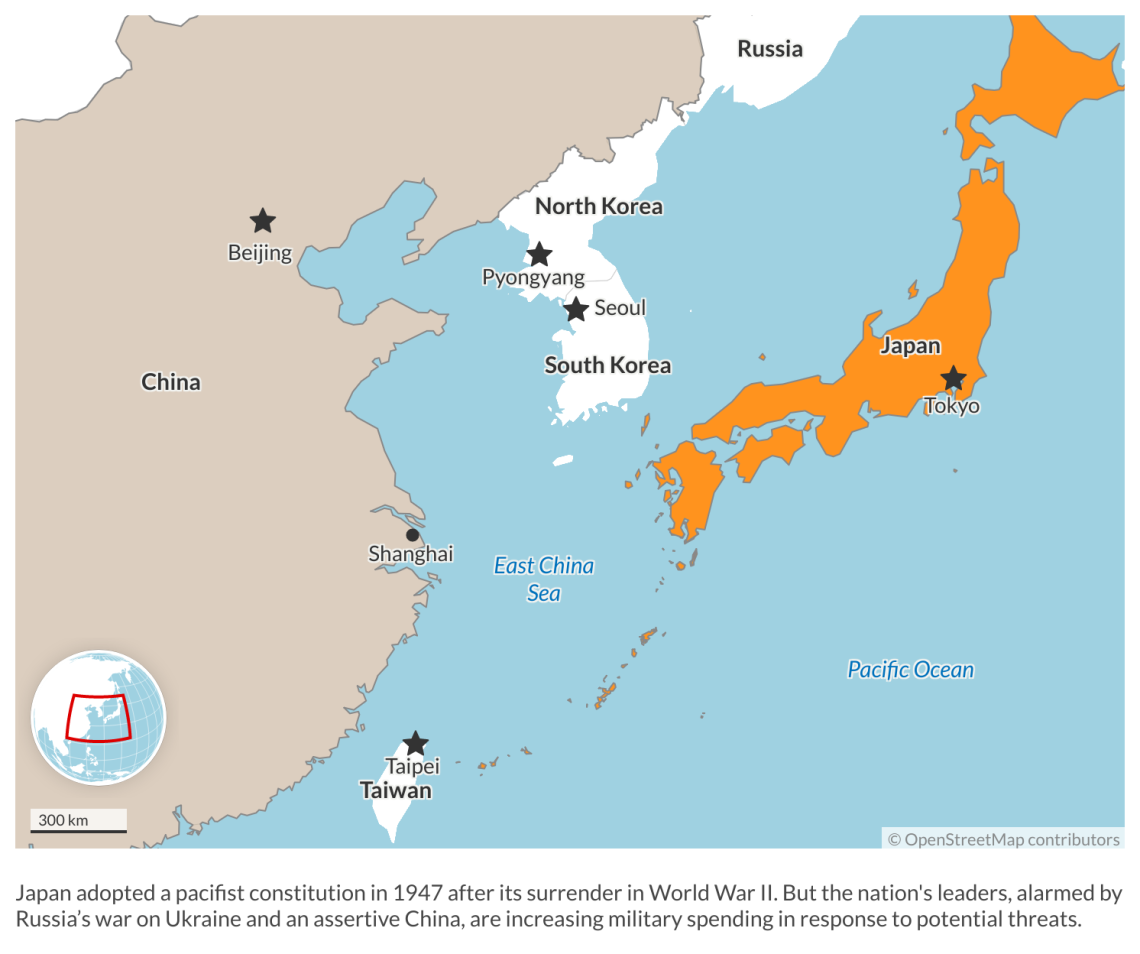

Both Germany and Japan emerged from World War II defeated and devastated. Both learned their lesson and, once the guns had gone silent, focused all their energies on reconstruction and the peaceful pursuit of economic ambitions. Both became wealthy because they could leave the costly provisioning of military defense to their allies, most notably the United States. In the case of Japan, this dependency on American protection was even more pronounced. The country got a new post-war constitution in 1947, drafted under the supervision of U.S. General Douglas MacArthur. It is largely pacifist and restricts military capacities to self-defense.

Following the years of reconstruction, Japan comfortably settled under the U.S. security umbrella. Japan served as a valuable forward base for American defense, an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” that seemed safe under Uncle Sam’s firm and unwavering protection. There were Japanese on the pacifist left who wanted the American bases scrapped, but most were at ease with the American presence. It came, therefore, as a shock, when President Donald Trump criticized Tokyo for not doing enough for its defense and signaled a dangerous turn toward isolationism. The late Shinzo Abe, who served almost nine years as prime minister ending in 2020 before his assassination in 2022, perfectly understood what was at stake and intensified the nationalist drive of Japan by expanding its geopolitical heft in the Asia-Pacific.

The rude awakening came especially from the Korean Peninsula, but also in the East China Sea and in Southeast Asia. North Korea has provoked Japan time and again, with the launching of ballistic missiles, some of which traversed Japanese air space. In the East China Sea, the Senkaku Islands, which are contested between China and Japan, have faced repeated Chinese violations of Japanese exclusive zones. In the South China Sea, Tokyo has been reacting with growing alarm and increasing security concerns to the escalating tensions between the Philippines and China. Here we have the open violation of the territorial waters of a sovereign state.

As if this were not enough of a challenge for Japan’s security, it was to be expected that sooner or later the Pacific Ocean, too, would attract the attention of Beijing. At first Taiwan and the People’s Republic competed for diplomatic relations with remote island nations. Central America, the Caribbean and the Pacific remain the last realm of Taiwan’s foreign relations. Currently four Pacific states – Tuvalu, the Marshall Islands, Palau and Nauru – maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan. Earlier, most Pacific Island nations had opted for Beijing, which was ready to open its purse for generous development aid in return.

Read more by Urs Schöttli

Fear of China brings Japan and South Korea closer together

Realism overtakes wishful thinking in Japan

Multitasking for Japan’s strategists

Geopolitics shapes development aid

For a long time, Japan saw the Pacific Ocean as a backwater. During the longest part of the Cold War, the Soviet Union had no maritime power there that could have challenged the U.S. Washington began to worry about the projection of Soviet naval power in the Pacific Ocean only toward the end of the Cold War. It was a late flickering of Russian imperialism. Of course, Japan took note of Moscow turning the Sea of Okhotsk, which borders on Russian and Japanese land, into a sanctuary for the Soviet fleet. But the scant interest of the Japanese in the Pacific was also because, under Mao Zedong and in the first decades of modernization under Deng Xiaoping, China had no naval power worth worrying the Japanese.

In these “carefree” times, Tokyo looked at the Pacific Island nations from a purely developmental point of view. Whether through institutions of the United Nations or bilateral programs, Japan has figured among the most generous nations in the world. In the Pacific region, the Pacific Island Forum (PIF) and the Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM) play an important role. The focus is on support for joint initiatives of the Pacific Island states in fields such as health, infrastructure, climate change and disaster management as well as maritime issues.

Currently, there is growing concern that Russia’s benign post-Cold War presence in the Pacific is over. Tokyo has noted that Russian President Vladimir Putin, even during the war in Ukraine and when his Black Sea Fleet was under attack, ordered naval exercises in the Far East. It was a demonstration to the world that, if needed, Russia can operate on several fronts and, particularly worrisome to Japan, that Moscow is cooperating with China. Fearing encirclement with important waterways in the Pacific Ocean under threat, some Japanese security experts are advocating the creation of an “East Asian NATO.” Beijing, of course, views this from an alarmist point of view and objects to the “revival of Japanese militarism.”

Every potential theater of war is different. The North Atlantic Treaty is unique and cannot be replicated in the Far East and in the Pacific Ocean. Tokyo already faces substantial economic, political and demographic challenges. With new and growing Chinese threats, it needs reliable allies.

In the Pacific, Japan’s paramount interest is in U.S. military preeminence. While Tokyo has been reaching out to Southeast Asia and India and is coordinating within the greater Indo-Pacific region, neither India nor any of the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has convincing military power in the Pacific. Australia and New Zealand are possible allies. They are part of the region and already have a network of cooperation with the Pacific Island nations.

Then there is France, which is a Pacific power through its overseas territories. Remarkably, France is not part of the new frameworks such as the Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with the U.S., India, Australia and Japan) and the AUKUS format (Australia, UK and U.S.). In this area, there is room for a French presence, which would add a direct European connection. Japan is keenly aware that a Chinese attack on French territories would get Europe involved.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

Likeliest: U.S. and Japan deepen alliance to counter Chinese threat

The U.S. and China are the only global superpowers. They are in fierce competition with each other. We must assume that there will be areas where American and Chinese interests clash and where the U.S. cannot and will not give in. These crisis spots are spread over the globe, although now predominantly in Asia. The Pacific Ocean is the top focus of American security. The U.S. is an Atlantic and a Pacific power. If the U.S. does not control the Pacific Ocean, the West Coast and, indeed, the Western Hemisphere will become vulnerable.

And this is where Japan emerges with its experiences and ambitions that shaped its fate in the Pacific War. The competition for control of this ocean was decisive in several ways. At the beginning of the hostilities, Japan’s supplies and livelihood were strangled. The strike against Pearl Harbor was an ultimate attempt to break what was perceived as U.S. encirclement. Equally, Washington saw the maritime advance of Japan, be it in the Pacific Ocean, in Southeast Asia and in the Far East, as a decisive attempt to move the war front closer.

Looking at today’s situation we can see the same dilemma facing the U.S. and China in their epic rivalry. It must be the long-term goal of China to move the frontlines from its own coasts far into the watery immensity of the Pacific Ocean. By assisting the island nations, Japan serves its goal of reducing China’s influence in an area that is the advance front both for itself and for the U.S.

Unlikely: Chinese military action and Western appeasement

Two undesirable scenarios are unlikely.

The first one would take place if China’s worries about U.S. encirclement become so acute that Beijing seeks a military solution. This could lead to a situation like the outbreak of the Pacific War, when Japan felt its existence was threatened. Today, a descent into armed conflict could come through an underestimation of American power and a misreading of the willingness of U.S. global forces to confront China.

The second one is appeasement. While the U.S. is not likely to become isolationist even if Donald Trump returns to power, the specter of accommodation might emerge elsewhere.

Japan’s important role in teaming up with the U.S.

In the most likely and desirable of these possible scenarios for the bilateral U.S.-Japan relationship, Tokyo’s new emphasis on security will become part of the Western strategy to contain China. The late Prime Minister Abe stood for this new approach and his successor, Fumio Kishida, seems to stay the course.

However, what happens if Japan adopts a policy of appeasement toward China? This might happen both because of China’s overwhelming military power and because of Japan’s weakening demographics and economic power. Unlikely as this scenario might look now, one must be aware that the longer-term prospects do not look promising for Japan. The country’s economy is losing steam, while Germany and India are gaining strength among the world’s top five economies. (The U.S. and China are safely ensconced as the No. 1 and No. 2 global economies, respectively.)

Even more worrying, the demographic trend points to Japan becoming a medium power, not much more populous than a united Korea. Of course, demographically, the prospects for China do not look very promising either, albeit not as dramatic a population drop as Japan’s. With these prospects in mind, a substantial number of Japanese might veer toward advocating accommodation rather than confrontation with China.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.