The enduring value of Japan’s emperor

Though Japan’s emperor holds no political power, he is much more than a figurehead: he is an essential part of Japan’s social contract. The monarchy has provided stability and unifies the country’s social structure. With Japan facing challenges, its new emperor will play a key role in speaking for the people and influencing policy decisions.

In a nutshell

- Japan’s monarchy plays a central role in the country’s social cohesion

- The system has helped bring postwar prosperity and peace to the Japanese

- The new emperor can build upon this success in the face of new challenges

Japan’s monarchy is unique: Its dynasty is the world’s longest-reigning, yet the country lacks many attributes associated with having a king or queen. In the allocation of political power and in the character of its institutions, Japan resembles a republic more than a monarchy. However, the emperor is much more than a crowned head of state. He is an essential part of Japan’s social contract.

In 1947, two years after Japan had surrendered at the end of World War II, the country got a new constitution, written and promoted by the United States. This basic law has not been changed since. In Article 1, the emperor is described as the symbol of the unity of the Japanese people, with whom sovereignty rests: “The Emperor shall be the symbol of the State and of the unity of the People, deriving his position from the will of the people within whom resides sovereign power.” The articles thereafter precisely describe the tasks and obligations of the emperor.

Ancient institution

In Asia, as in other parts of the world, monarchies are rare. Today only Japan, Thailand, Brunei, Malaysia, Bhutan and Cambodia are constitutional monarchies. China’s last dynasty, the Qing Dynasty, was abolished in 1912, when the Republic of China was established.

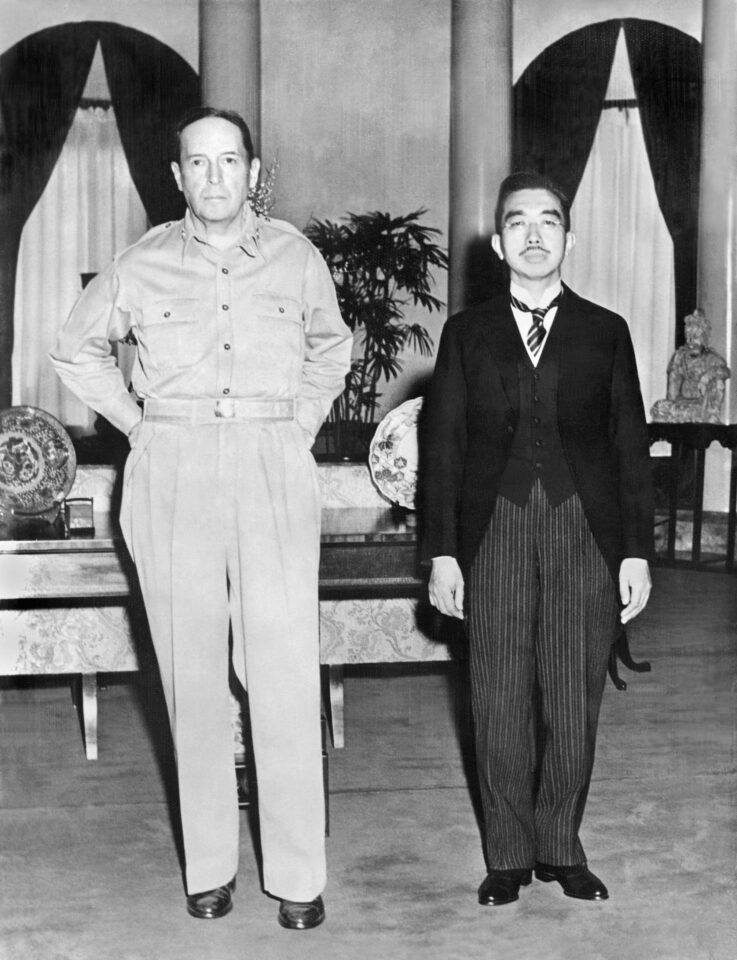

The end of the Pacific campaign of World War II and the defeat of Japan in 1945 could easily have brought about the demise of the imperial system. Many experts and much of the U.S. public believed that as the ultimate authority and commander of the armed forces, Emperor Hirohito was personally responsible for the war crimes committed by Japanese troops in China, Korea and Southeast Asia. They wanted Hirohito to be deposed and brought before the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

MacArthur rightly recognized that the emperor could facilitate a peaceful and orderly transition to civilian rule.

However, mainly due to General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) in Japan, this did not happen. Gen. MacArthur rightly recognized that the emperor could be a useful tool to facilitate a peaceful and orderly transition to civilian rule.

Though foreign interventions can go horribly wrong, in Japan’s case, it went right. Soon after the surrender, violence ceased throughout the archipelago. In respect for the defeated country, the act of surrender had not taken place on Japanese soil, but on board an American warship – and it was not the emperor who signed the treaty of surrender.

While the Japanese public had no illusions about who was in charge after the surrender, Emperor Hirohito proved to be of great help in Japan’s transition from feudalism to a modern nation-state. Until the surrender, the emperor had a god-like status, and Shinto was the state religion. All this was removed in 1945. From then on, Emperor Hirohito played a constructive role in securing healthy continuity and in supporting reform and peaceful development, both needed for reconstruction after the devastating Pacific War.

Interestingly, once the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo enshrined the souls of convicted war criminals, Emperor Hirohito never again set foot there. His successor, Emperor Akihito, followed the same path and dedicated many of his efforts to repair Japan’s relations with the countries it had attacked during the war.

China’s long history shows a succession of dynasties. Repeatedly, emperors were deposed and dynasties overthrown because they had lost the “mandate of heaven.” This goes back to the days of Confucius. If the emperor no longer fulfilled his duties toward his subjects, if the country suffered under his rule and the people lived in poverty and insecurity, the emperor could be removed. In contrast to this revolutionary tradition, Japan has an unbroken continuity of emperors who trace their origin to the sun goddess Amaterasu. Even during the recent transfer of the throne from Emperor Akihito to the new Emperor Naruhito, reference was made to the mythical origins of Japan’s rulers.

Dignified transfer

It is unusual for a Japanese emperor to resign. Until Emperor Akihito handed over power to his eldest son, there was an extensive debate as to whether the move might prove destabilizing or even indicate a division in loyalties. It was evident, however, that Emperor Akihito wanted to resign because of his failing health and his concern that he might not be able to fulfill his duties any longer.

The transfer of power put to rest any doubts that having an emperor emeritus might be disruptive. This realization was crucial, since it is widely known that on some important issues regarding the emperor’s role, both Akihito and Naruhito hold opinions that are at odds with the country’s most conservative circles.

On the whole, the imperial household upholds the highest standards of dignity.

On the whole, the imperial household upholds the highest standards of dignity. Japan does not have the kind of yellow press that is read by a large segment of the British population. While the general public in the United Kingdom is regularly entertained with reports of scandals in and around the extended British royal family, nothing damaging or critical is reported about the Japanese court. This is also because the imperial household is highly restricted. In fact, the innermost core consists of the emperor himself and his male descendants; female children leave the household once they marry.

Male succession continues to be an issue of concern. The constitution itself does not explicitly decree that succession must be limited to male descendants. This is simply the customary practice of the imperial household. Many Japanese would welcome a female succession, but conservative members of society find the idea unpalatable, as it goes against long-held tradition. On the other hand, there is worry that the imperial family could die out through lack of male offspring. The new emperor has no male child. His successor is his younger brother, Crown Prince Fumihito, whose 12-year-old son, Prince Hisahito, is third in line to the throne.

Social contract

The succession ceremony held on April 30, 2019, in the imperial palace was short and dignified. In the first session, Emperor Akihito declared his resignation. In the second, the new emperor promised to work for the good of the Japanese people. His short statement was followed by an equally concise declaration by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The formal enthronement will take place on October 22, for which Japan expects the presence of many foreign dignitaries.

While the Japanese are generally not ardent monarchists and consider the emperor to be a sensible solution for the role of head of state, he is an important pillar of the specific Japanese social contract. Japan is unique not only for its ethnically, culturally and religiously cohesive population, or because of its status as an island nation, but most importantly because of its social structure. The overwhelming majority of Japanese consider themselves middle class. Indeed, by outward appearance, Japan is a nation without backward regions or glaring discrepancies in wealth.

The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was established in 1955 and has been in power almost ever since. Currently, Prime Minister Abe is setting a new record in political longevity. The unparalleled electoral success of the LDP is also due to social structures that reach beyond the Meiji Restoration to the times of the shogunate. The members of parliament are the “samurai,” the leaders of the various factions within the LDP are the “daimyos” (dukes) and the prime minister and party leader is the shogun. Constituencies are similar to local lordships. The Japanese parliament has many second- and even third-generation politicians. They enjoy the almost feudalistic trust of their constituencies.

Until the Meiji Restoration in the 1860s, the emperor was subordinate to the shogun. All political and military power rested with the latter dignitary, while the emperor was marginalized and at times even forgotten. Under Emperor Meiji (1867-1912), this changed and the emperor cult culminated in the fateful empire that brought so much pain and destruction to large parts of Asia and Japan itself. After the surrender and with the help of the U.S., Japan made a fresh start, which brought the country unprecedented prosperity and social peace. Having a constitutional monarchy where the political decision-making is firmly in the hands of the executive branch has proven to be a solid foundation for postwar Japan.

The era beginning on May 1, 2019, has been dubbed Reiwa, which means ‘beautiful harmony’.

Watching the transition in the imperial palace, it seems clear that this success story will continue under the new emperor. Each imperial reign in Japan receives a name. Emperor Akihito’s is Heisei (“peace everywhere”), while the era beginning on May 1, 2019, has been dubbed Reiwa. The government decided on the term, which according to the Japanese Foreign Ministry means “beautiful harmony.” It is a clear indicator of the direction Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s reforms are intended to take the country.

Scenarios

Japan faces several serious challenges, not least the rise of China, the disengagement of its most important ally, the U.S., the aging and shrinking of the Japanese population and the global impact of climate change. Under these circumstances, a stable social order and solid institutions of governance are crucial. While economic reforms and a continuation of Prime Minister Abe’s policy of opening up Japan to Asia and beyond are very important, the recent change on the Chrysanthemum Throne reflects a generational shift throughout Japanese society.

As during the Meiji Restauration, Japan’s elites are once again being called upon to undertake historic reforms. While the emperor cannot influence policy decisions (which remain the undisputed privilege of the government and of parliament), he can, through his interaction with the people at large, help shape what course reforms eventually take.

Many remember how Emperor Akihito sided with the people when big natural disasters such as the Kobe earthquake of 1995 and the Tohoku tsunami of 2011 took place. His modest and compassionate demeanor won him great public affection, and he was seen as a monarch who displayed the right sentiments toward his people. Thanks to him, Japan’s monarchy has never been more solidly rooted among the people than today, when his son begins a new reign.