Is multi-alignment a path to chaos or order?

A truly multipolar world would dilute the importance of China and the United States, but the two superpower rivals are not going to cede influence easily.

In a nutshell

- Middle powers like India and Brazil seek independent foreign policies

- Expanding BRICS to 11 members and beyond will shift geopolitical realities

- China uses the group to promote its interests and weaken the United States

Does multi-alignment provide middle powers with greater options for foreign policy, security and defense? The reactions of states like India and Brazil to the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East are based on their own perceived interests, rather than alignment with China, Russia or the United States. Nevertheless, advocacy of multipolarity at a time of heightened tensions may play into efforts by Beijing and Moscow to further undermine the Western-led international order and boost their own global standing.

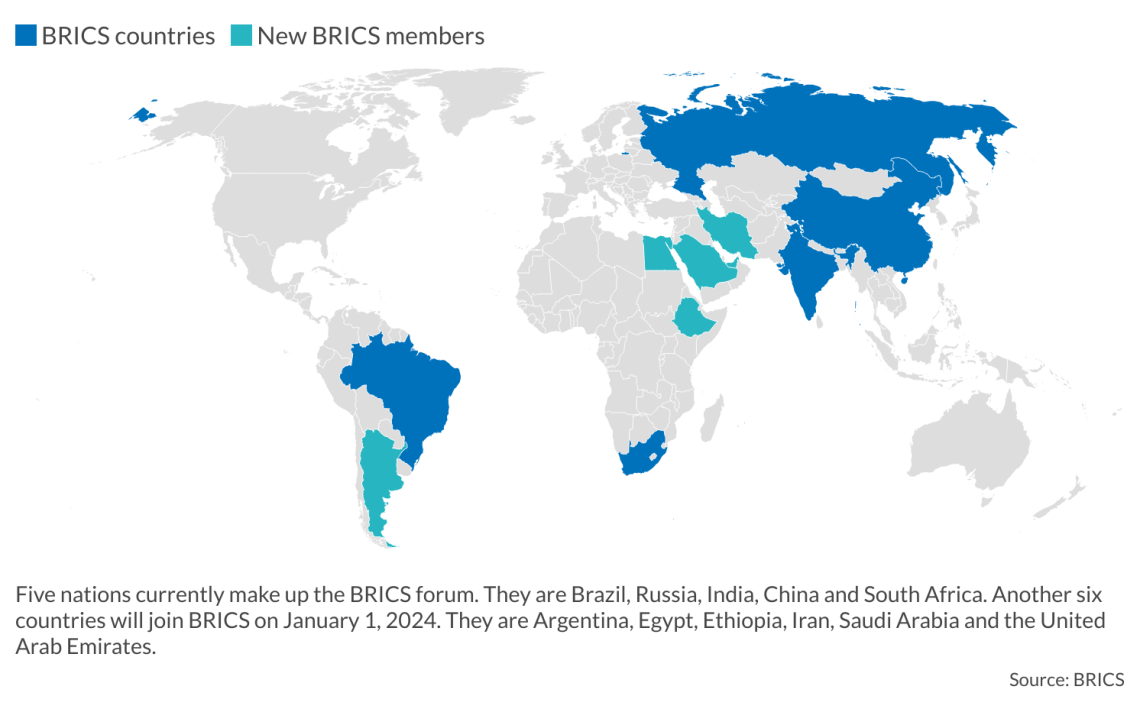

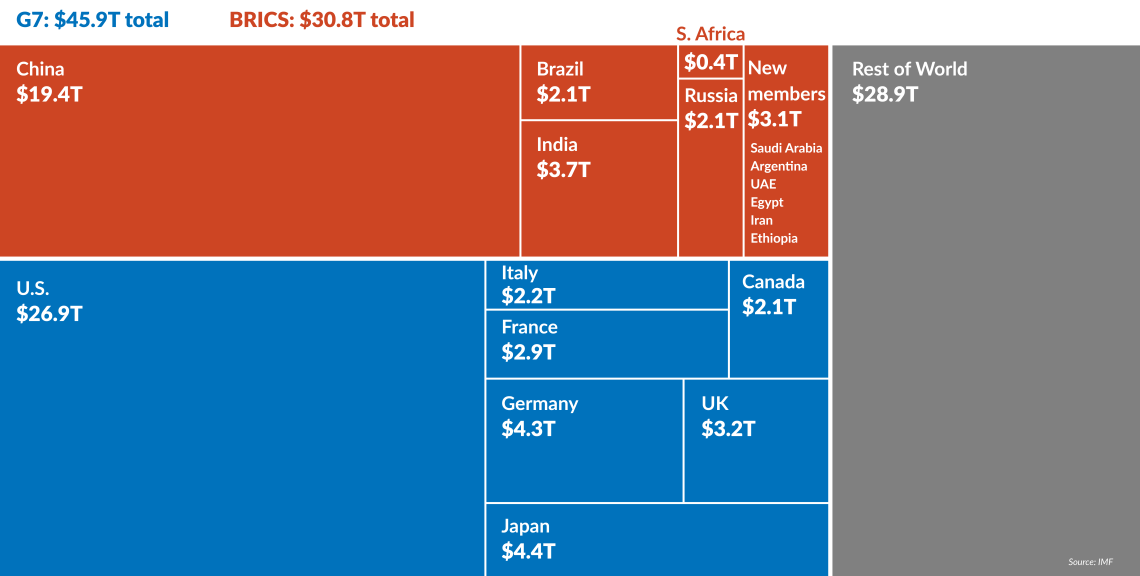

The planned enlargement of BRICS to 11 members in 2024 highlights these emerging trends. This enlarged grouping will bring together states with almost a third of the world’s economic output, nearly half the planet’s population and oil production and a quarter of global exports. This development points to at least three possible outcomes: accelerating multipolarity, China’s ascendency or persistent American global primacy.

The five current BRICS members – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – agreed at their August summit in Johannesburg to expand the group with invitations to another six countries: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Several of these countries can be considered middle powers, in terms both of geopolitical weight and of their political oscillation between China and the United States.

BRICS members see the group as a counterweight to Western-sponsored intergovernmental forums, such as the G7 and the G20, and as a boost to the pursuit of their own national interests. BRICS enlargement has increased speculation about a broader shift to a multipolar or multi-aligned world.

But Brazil and India were not enthusiastic about admitting new countries, which would reduce their relative importance and distract attention from their own priorities, including their goal of becoming permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. Initially, South Africa was also skeptical. In agreeing to add members, they gave in to Chinese pressure and inducements.

For China, the grouping is a means to weaken the influence of the United States and to strengthen its own international strategic and economic outreach. This reinforces China’s “no-limits” partnership with Russia without involving a troublesome military alliance. Russia, faced with growing sanctions following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, is looking for support from BRICS and the Global South.

More about BRICS

Building a bigger BRICS

BRICS’s hazy outlook

The real message from the BRICS summit

Diverse and conflicting priorities

The profiles and priorities of the 11 nations are diverse and often conflicting. They range from richer and middle-income economies to poorer and developing countries. They include both large exporters and large importers of commodities and energy. Nuclear-armed countries gather with states possessing far less military power. Communist China will sit in expanded BRICS meetings alongside theocracies, autocracies, democracies and secular states.

China and India have a simmering border conflict. China is a leading arms supplier and de facto ally of Pakistan, India’s historic adversary, while Russia is now India’s main source of crude oil. India abandoned a regional trade agreement (RCEP) before it was signed because of security and trade concerns arising from China’s membership. At the same time, New Delhi is seeking closer links with the U.S., France, Greece and other Western countries. India stands to gain from U.S. limitations on technology, trade and investment with China, which faces an unprecedented economic slowdown.

The rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, brokered by China, remains fragile. Egypt’s relations with Iran are strained, despite a tentative thaw. Ethiopia, the enlarged group’s poorest member, is fraught with conflicts, not least with Egypt over Nile waters. Argentina is dependent on the International Monetary Fund and U.S. backing to withstand its present economic crisis. The two candidates who qualified in October for Argentina’s upcoming presidential runoff election on November 19 are split on whether to join BRICS.

Facts & figures

G7 vs. BRICS

BRICS has limited operational capabilities

BRICS lacks an institutional structure, unified market, standards-setting authority, budget and secretariat. The BRICS New Development Bank operates on a far more limited scale than the World Bank or European Investment Bank. The Brazilian president at the recent summit mooted the introduction of a BRICS currency. This idea has no foreseeable prospect, with China as the second largest holder (after Japan) of U.S. Treasury bills. However, BRICS does aim to increase mutual trade, with settlement in their own currencies alongside new digital payment systems.

BRICS enlargement will make the respective interests of participants even more divergent. It will remain a loose grouping with shifting patterns of cooperation and rivalry depending on the issue at stake. Nonetheless, BRICS confers a sense of participation and prestige on less influential participants and gives them a forum to talk with each other about global challenges.

In response to BRICS enlargement and increased Chinese and Russian involvement in the Global South, Western states have stepped up their own efforts to court developing countries. The expansion of the G20 to include the African Union, decided at the recent summit in New Delhi, is a case in point.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

First scenario: Multi-alignment takes hold

The premise of the first scenario is that BRICS, however limited operationally, exemplifies the drift of the modern world toward multipolarity or multi-alignment. In this narrative, the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine accelerated the decline of the U.S.-led international order. Proponents of this scenario call for the IMF, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, the G7 and the United Nations Security Council to be overhauled to better reflect current geopolitical realities.

Under this scenario, developing countries and middle powers like Brazil, Indonesia or Turkey, are increasingly empowered to pursue their own interests, which often clash with those of Western states and organizations. They adopt a pragmatic, transactional, multi-aligned posture, increasingly taking their own stands on global and regional issues, whatever the positions of Beijing, Moscow or Washington. They see pragmatic cooperation with states of any political complexion, long practiced by great powers, as legitimate.

In this narrative, new international bodies like BRICS, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization better express their interests than Western-sponsored structures. Participants are not discouraged by Chinese and Russian backing for such arrangements because it comes without the human rights, environmental and governance strings attached to Western assistance. They view economic development, better infrastructure and poverty reduction as higher priorities than governance or climate goals. Advocates of this approach claim that democracy follows development rather than vice versa.

Global South governments are uneasy about Russia’s war on Ukraine. Apart from the suffering and damage caused, grain supplies have been disrupted and inflation given a new jolt. The principles of national sovereignty and territorial integrity, defended by Ukraine, are crucial to their own security and survival. But they see sanctions as harmful to their own interests and often regard Russia’s role in the war as no more egregious than Western military interventions in Vietnam, Iraq, Libya and elsewhere.

This scenario treats the world today as neither bipolar, as during the Cold War, nor unipolar, as during the first 20 years after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union. It is, rather, multipolar, multi-layered or multi-aligned. In this setting, states are ready to be pragmatic on trade and investment, foreign assistance and efforts to acquire armaments and advanced technology.

But multi-alignment is a self-contradictory term. Alignment implies the choice of an alliance or orientation. This highlights a broader contradiction between a desire to shake off post-colonial or post-imperial dominance and a willingness by middle powers to engage with major powers whose principal goals are no less self-serving.

Second scenario: An ascendant China asserts its interests

Proponents of the multi-alignment scenario tend to depict China as mainly interested in stability, cooperation, development and peace, echoing Chinese propaganda. But a second scenario views China’s support for multipolarity, including initiatives such as BRICS, as a means to promote its own interests rather than shared regional or global goals. There is a widespread perception in Washington that China aims for hegemony in the Indo-Pacific , though some China watchers question this ambition.

Beijing seems to favor an international configuration in which no single state is dominant. It was uncomfortable with the unipolar moment of U.S. strategic superiority that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and rejects bipolarity, or a new Cold War, as the future basis for international relations. In this narrative, Beijing’s outreach to developing countries and middle powers is part of a drive to raise its own profile, play down Western-led international forums and to create alternative networks in which its own role is predominant.

China’s instruments of choice for expanding its international influence are trade and investment, notably in infrastructure and advanced technology, although its military capabilities are also steadily growing. Its investments generally involve little transfer of technology, local employment or help with sustainable development. But investment by Chinese firms is welcomed in Asia, Africa and Latin America as free from the strings attached to Western concessionary finance and development assistance. Beijing rejects the claim that it uses debt dependency as a means to attain political control. It is gradually adopting soft power vehicles like education, training and culture and supporting regional cooperation projects in Africa and elsewhere.

China’s questionable status as a developing country as well as its preference for economic influence over risky foreign adventures enhance its credibility with the Global South, a term embraced by Beijing. BRICS is widely cited as emblematic of this approach. Yet China can scarcely be regarded as a mere first among equals in BRICS and other international settings sponsored by Beijing. China’s size, economic and technological prowess, critical resources, foreign direct investment, nuclear status and mounting military capabilities ensure it a preeminent role.

China has a 70 percent share of the BRICS gross domestic product and a 50 percent share of its internal trade, although these will fall somewhat with the accession of wealthy Gulf energy producers. But members find BRICS sufficiently supportive of their own interests and opinions for them to overlook China’s dominant position in the grouping.

Yet China faces not only an unprecedented economic slowdown but also a subsidy and critical-resources war with Europe and the U.S., especially in green technologies, with increasing trade and technological restrictions. If, as with its previous zero-Covid policy, this gives rise to domestic discontent, Beijing may react by increasing repression at home and cranking up tensions abroad. Yet it is also ready to explore the scope for conciliation with Washington to reduce tensions that harm its economy.

Third scenario: American primacy will persist

In this third scenario, the U.S. retains its military, economic and technological preeminence, with the dollar unchallenged as the principal trade currency and repository of wealth. China is wavering and may not soon become the world’s largest economy, given its current slowdown.

Several key BRICS countries continue to rely on the U.S. for their security and prefer to hold Beijing and Moscow at arm’s length. As evidence, U.S. and French arms exports to Asia and other areas of political strife have increased considerably in recent years, whereas Russia’s have fallen substantially.

Under this scenario, the U.S. pushes back against Beijing’s appeal to middle powers by strengthening its own cooperation with countries in the Indo-Pacific.

The U.S. wants to revitalize the G7, from which Russia was suspended after its illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, and the G20, whose recent inclusion of the African Union stole the thunder from China’s success in enlarging BRICS. Like China, the U.S. increasingly favors forums, networks and informal structures in the Indo-Pacific. This appeals to the nonaligned who are wary of China’s ascendancy but want to keep their distance from Washington as well. It also avoids ratification battles in the U.S. Senate.

Washington has created a network of partnerships to promote international cooperation and discourage Beijing from risk-taking in the Indo-Pacific. These include the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, composed of Australia, India, Japan and the United States; AUKUS, the trilateral security partnership among Australia, the UK and the U.S., involving the sale of nuclear-powered submarines to Australia; as well as the “I2U2,” which promotes economic cooperation among India, Israel, the United Arab Emirates and the U.S. At the same time, the U.S. has reinforced its strategic partnership with Vietnam, which is a bulwark against Chinese expansion in the South China Sea, and its dialogue with the Philippines.

Such initiatives, and those forged by American allies France and the UK as well as the European Union, convey to Beijing and Moscow that the West will continue to engage in the Indo-Pacific and adjoining regions. This display of determination is intended both as deterrence and as an incentive to Beijing to reduce tensions and to explore the scope for cooperation.

The prospects for balancing multi-alignment and engagement with the West

The international system will display aspects of each of these three scenarios in the years ahead. Middle powers will seek to leverage their comparative advantages to the fullest, challenging or cooperating with major powers depending on the issues at stake. China’s assertiveness, clothed in the language of multipolarity, will continue to grow, whenever this reinforces internal political control by the ruling elite. The military, economic and technological preeminence of the United States will persist, increasingly challenged by China. But unless the U.S. succumbs to isolationism following elections in 2024, it will show more readiness than in the past to engage with governments of different complexions, including those opting for multi-alignment.

The U.S. and its allies can counterbalance China’s influence on middle powers by showing that they are committed to long-term involvement in the Indo-Pacific, Africa and Latin America. The best way to encourage middle powers to maintain a multi-aligned approach, which includes cooperation with the West, is to increase investment in these regions, which, in turn, requires a stable business environment.

Overall, the scenarios envisioning multi-alignment as a new norm and persistent American predominance are the most probable over the coming decades. China’s influence in the Global South and beyond will continue to grow. But pushback from the U.S. and its allies, China’s internal challenges and the tradition of a China-centric Middle Kingdom mean that its global ascendency will be largely confined to certain sectors.

Editor’s Note: This report is based on research for a workshop organized by Kings College London and Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies in Bologna in October 2023.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.