Modi aims to leave a lasting mark on India

Narendra Modi wants to make profound reforms to the economy, ideology, and welfare of India. The reforms have met stiff resistance so far. Add to this the rising importance of Hindu nationalists, and 2020 looks set to be his most tough year.

In a nutshell

- In his second term, Narendra Modi wants to solidify his legacy

- He has made several major, controversial changes

- Resistance to his agenda is increasing in the courts and states

This new series of GIS reports examines how effectively countries are ruled and the consequences of governing systems for economies, societies and nations’ development prospects.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi begins 2020 with a surfeit of political capital, a flagging economy and a determination to use his second term to leave an indelible mark on India. After a first term in which he faced no serious political opposition, the prime minister was reelected last year in a landslide. Polls continue to show his personal popularity in the 70 percent range, though mass protests in December and January took the sheen off his government.

Based on the frantic pace of legislation in the last half of 2019, one can see three main elements of Mr. Modi’s policy agenda. One is economic: pushing ahead with reforms designed to achieve his target of adding $2 trillion to India’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 2025. The second is ideological: attempting to weave elements of his Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) Hindu revivalism into India’s legal and social fabric. The third element of the agenda is laying the foundations for a 21st-century welfare system in India to guarantee the BJP’s future and his own place in history.

Many of the reforms carried out during Prime Minister Modi’s first term sought to reduce India’s outsized black economy.

In carrying out each of these, the prime minister will face challenges from the judiciary and India’s complex federal structure. Amid all this, one of the reform goals Mr. Modi laid out in his first few years as prime minister is in danger of being forgotten: reversing decades of increased central authority within the Indian federal system.

Economy

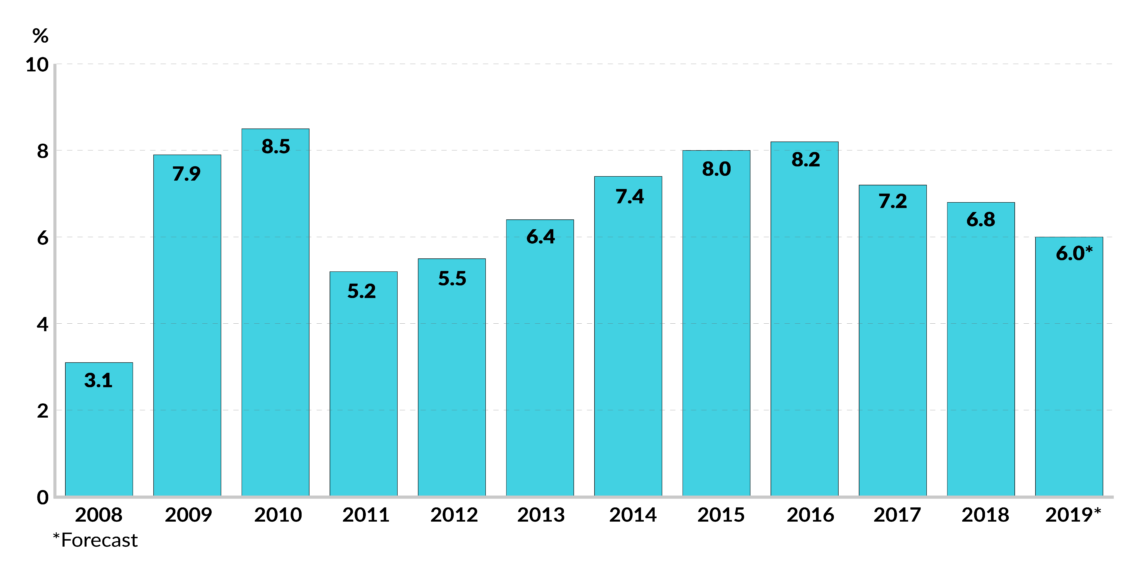

The Indian economy, in part because of a global slowdown but mostly because of regulatory and financial bottlenecks, has seen a sharp drop in growth. In the fiscal year ending in March 2020, GDP growth is likely to come in at six percent and fall another percentage point in the following year.

Facts & figures

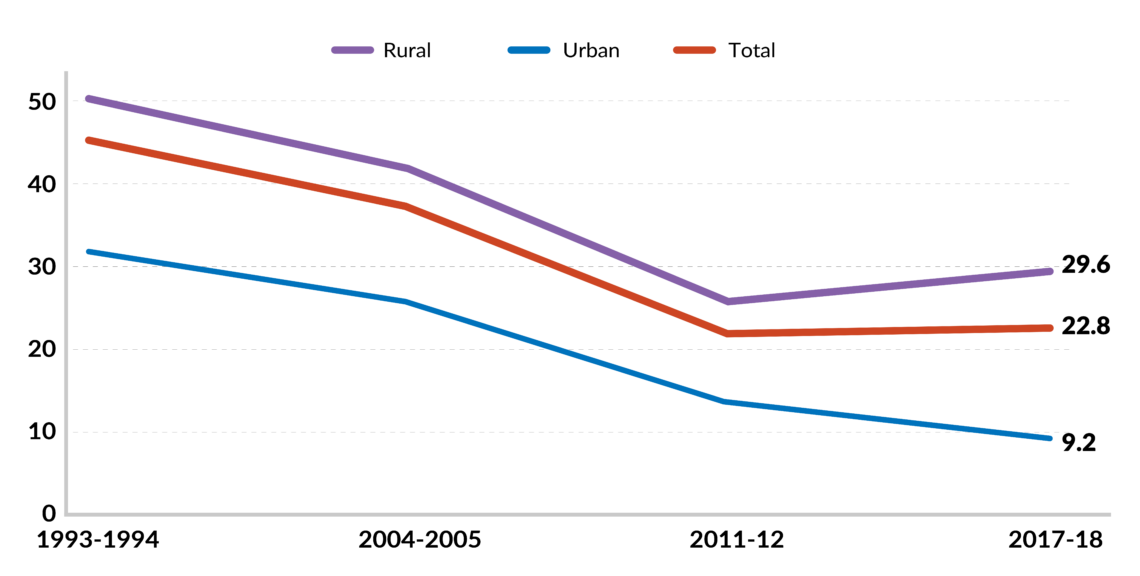

Many of the reforms carried out during Prime Minister Modi’s first term sought to reduce India’s outsized black economy. Implementation, however, has been haphazard and the expected expansion of the formal sector has not occurred. Over the past six years, a net 30 million Indians fell below the poverty level, according to one disputed study. And there is evidence of economic gridlock: the banking sector is sitting on 2 trillion rupees (about $28 billion) of excess capital unwilling to lend for regulatory reasons, while the manufacturing sector is starved of credit.

Even before his reelection, Mr. Modi had been exploring how to liberalize the economy further. He commissioned a prominent free-market economist, Surjit Bhalla, to lay out a blueprint for further reforms. The subsequent report recommended a sharp cut in corporate taxes, lower interest rates, a huge privatization drive and a reversal of the past five years of protectionism. The first two recommendations have already been enacted while the third is underway, with more than 40 state-owned companies earmarked for sale. The widening fiscal deficit has imbued privatization with a sense of urgency.

Facts & figures

One path the BJP will continue to follow is making the Indian economy greener. Last year, India was rated the sixth-best country by the Climate Change Performance Index. This results from a deep environmental streak within the Indian right wing and Prime Minister Modi’s desire to get the Indian economy to leapfrog development stages. Just after his reelection, the motor industry beat back a radical government proposal on electric vehicles. Climate remains a major concern of the Modi administration and the green side of the prime minister’s agenda will be evident in his policies over the coming few years.

Critics have argued it is “factor of production” reforms – especially land and labor – where action is needed the most. Mr. Modi’s officials argue that under the Indian constitution, these are largely the prerogative of the states; the central government can only provide guidance. The prime minister sought to encourage states to loosen the corset of India’s tight laws on land ownership in his first term. He had limited success. In his second term, he has sought to streamline the hundreds of Indian labor laws and regulations, at both the central and state level.

What he has failed to do so far, however, is inspire a more fundamental debate about the constitution’s Seventh Schedule, which apportions power between the central, state and local governments. The head of the prime minister’s council of economic advisors, Bibek Debroy, repeatedly argued that since center-state relations “are now in the process of being transformed and new institutional arrangements have evolved,” the entire Seventh Schedule should be reviewed. So far, his plea has fallen on deaf ears.

Facts & figures

Governance in India

India is a federal parliamentary republic, comprising 28 states and nine union territories. Its current constitution came into force on January 26, 1950.

Executive branch

- The president is chief of state, while the prime minister is head of government. Cabinet members are recommended by the prime minister and appointed by the president

- The president and vice president are indirectly elected by an electoral college consisting of elected members of both houses of parliament for a five-year term. Following legislative elections, the prime minister is elected by members of the majority party in the lower house of the parliament

Legislative branch

- India’s parliament is bicameral. The upper house is called the Council of States or Rajya Sabha. Of its 245 seats, 233 members are indirectly elected by state and territorial assemblies by proportional representation vote, while 12 members are appointed by the president. Members serve six-year terms

- The lower house is called the House of the People or Lok Sabha. It has 545 seats; 543 of its members are directly elected in single-seat constituencies by simple majority vote, while the president appoints two. Members serve five-year terms

Judicial branch

- The highest court is the Supreme Court, which comprises 28 judges, including the chief justice. Justices appointed by the president to serve until age 65. Subordinate courts include the High Courts, District Courts and the Labour Court

Ideology

The most contentious part of Prime Minister Modi’s agenda is ideological. The policy is not secret; it has been part of the BJP’s worldview for decades. Hindutva ideology feeds on a perception that the Indian state practiced a form of secularism that discriminated against Hindus during its overtly socialist phase. Aided by the cultural dislocation caused by urbanization and economic churn, a nationalist form of this ideology has found a receptive audience in large swaths of northern and western India. Mr. Modi has used it to wed the BJP’s traditional upper-caste Hindu base to newer aspirational social groups, notably middle caste groups known as the Other Backward Class – a group from which the prime minister himself comes. The problem is that much of this alliance is based on the leader’s popularity rather than allegiance to the BJP, something the party wants to change before he departs the political stage.

Coming on the heels of several state election setbacks, Mr. Modi’s aura of invincibility is starting to dissipate.

Not all of the BJP’s policies have been illiberal. But it has used brute legislative numbers, polarizing language and limiting public debate to get its way. One of the first legislative acts of the second Modi government was to abolish the “triple talaq” divorce method. (By this method, Muslim men could divorce their wives instantly simply by uttering the word “talaq” three times.) Though the move empowered Muslim women and ended a regressive practice, the BJP did not consult the Muslim community. Abolishing the special constitutional status enjoyed by Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir had strategic drivers but again, notably lacked a consultative process.

Since December 2019, the prime minister has run into significant popular opposition because of the government’s efforts to tighten India’s immigration policies. It passed one law to fast-track citizenship for non-Muslim refugees, intending to win the votes of millions of poorly documented Hindu migrants from Bangladesh and Pakistan. Another decision was to resurrect an older proposal for a citizenship registry. Some have interpreted these steps as a BJP attempt to disenfranchise millions of Muslim immigrants and perhaps even citizens.

Happening at a time of heightened food inflation, student anger over right-wing interference in academic institutions and Muslim resentment at the BJP government as a whole, the immigration policy served as a lightning rod for public discontent. Coming on the heels of several state election setbacks, these developments are beginning to reduce Mr. Modi’s aura of invincibility.

Both actions also face institutional challenges. The Supreme Court of India will be ruling on the immigration policy. Several state governments, as they appoint the personnel to implement the policy, have said they will not allow the citizenship registry to work.

Welfare

The core of Prime Minister Modi’s popularity comes from the massive expansion of India’s welfare system under his watch. The Swachh Bharat (Clean India) campaign, accessible cooking gas and financial inclusion schemes were responsible for much of his first-term popularity. His unique twist was to use biometric identification and digital technology to target payments and keep costs in line. The second Modi government, wrote Swapan Dasgupta, one of the more erudite BJP leaders, will be both “pro-nationalist and pro-development.”

The core of Mr. Modi’s popularity comes from the massive expansion of India’s welfare system under his watch.

Prime Minister Modi has rolled out a new flagship welfare program for his second term, Jal Shakti (Water Power), with the promise of piped water for every Indian household in five years. The nascent healthcare program – a mix of controlled medicine prices, insurance and primary healthcare provisions – will also be expanded nationwide. The financial costs and administration of all these initiatives are already beginning to bite at a time when the capabilities of the Indian government are stretched. It has also run into external hurdles: attempts to control the prices of medical devices have become a headline issue in India’s trade dispute with the United States.

Mr. Modi’s most ambitious plan has been to create the basis of a new digital economy. Bits and pieces of this have already been accomplished, most notably nationwide biometric identification. However, the nation’s Supreme Court has intervened over data privacy issues. Also, opposition from the U.S. and the European Union to India’s stringent data localization requirements have put the brakes on this program as well.

Has Modi peaked?

The BJP has experienced several electoral reverses. The slowing economy was one reason the immigration protests blew up. The prime minister’s ideological legislative actions have caused fissures in his image overseas.

There is also a sense of imbalance within the administration. Mr. Modi’s first cabinet was a compromise between Home Minister Amit Shah, a saffron-dyed-in-the-wool party man with formidable organizational skills and deep ideological beliefs, and Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, a savvy lawyer well-networked within the cosmopolitan Indian establishment that the BJP dislikes. Mr. Jaitley’s death in August 2019 has meant Mr. Shah’s influence in the cabinet and bureaucracy has become disproportionately strong.

Prime Minister Modi’s ambitious plans for a new federal structure will suffer. Having run a state for three terms, he often argued the center must hand over more authority and more funds to the states. But as prime minister, he has seen many of his economic initiatives frustrated by the corruption and populism that plague many Indian states. He increased the state’s share of the country’s tax pool from 32 to 42 percent but moved to extend the authority of central regulators, especially in the economic field. With his political hold on the states weakening, this governance conflict of interests is unlikely to be addressed.

What is at stake is not Mr. Modi’s government but rather his ability to claim he placed India on the trajectory to future greatness. This is why New Delhi’s energies are turning increasingly to the economy. Multiple problems continue to hobble India, including a slowing global economy, endless regulatory and legal battles over poorly designed reforms, and the government’s anti-corruption drive. That last campaign, warned Rahul Bajaj, one of India’s most prominent industrialists, had made even businesspeople wary of criticizing the government.

Scenarios

The Modi government will become more accommodating over the coming year as the economic slowdown takes its toll. That stance is already evident at the local level, where the BJP has faced electoral reverses. By the end of 2017, the BJP governed more than 70 percent of India’s states; today it has less than 40. Nonetheless, Mr. Modi’s hold over the lower house in parliament remains rock solid: he has had no difficulty cobbling together necessary majorities in the upper house to pass bills. This may change as the opposition gains momentum.

What seems inevitable is that over time the BJP will become ever more dependent on regional allies (one source for its ability to pass radical legislation, whether sociocultural or economic) by the mid-2020s. The real test will not be over Hindutva policies, but unpopular economic initiatives such as privatization, where Mr. Modi will also have to tackle the right wing of his party. With the judiciary, state governments and civil society putting up increasing resistance to key elements of Mr. Modi’s agenda, 2020 seems set to be his most difficult year.

The prime minister will oversee a year of policy consolidation, with the focus on economic revival. In the past, the prime minister resisted the calls to relax the government’s fiscal deficit targets. This is set to change and the new budget in February will be marked by pump priming. The government will open the economy further to foreign investment and accelerate privatization.

Mr. Modi will reshuffle his cabinet and position himself as a centrist, in contrast to the more ideological Mr. Shah. The bureaucracy will undergo a steady and continuous churn as the prime minister works to create a more responsive administrative structure. He may return to the more ambitious plan of reversing the centralizing tendencies of decades of socialism. That agenda, however, is likely to remain on hold until India’s leader can show his mojo has returned.