Saudi Arabia’s energy ambition: From oil to gas

As oil grows out of fashion, Saudi Arabia is banking on natural gas. Not only can it help the country generate electricity, it can also provide a crucial basis for a robust petrochemical industry.

In a nutshell

- Saudi Arabia has significant natural gas reserves

- The country wants to tap into its shale resources

- Riyadh has ambitious plans to become a gas exporter

When people think of Saudi Arabia, they often think of oil. After all, it is the world’s largest exporter of the resource, and its economy is heavily dependent on oil revenue. Now, however, Saudi Arabia has grand plans for its reserves of natural gas. It has three main goals: to double gas production (including from local shale resources), to eliminate the use of oil in power generation and to become a gas exporter – all by 2030.

Saudi Arabia has plenty of natural gas, so it has a strong foundation on which to achieve these aims. However, the country has a better chance of reaching the first two goals than the third within the next nine years.

Lofty goals

Along with being the largest oil exporter, Saudi Arabia is the third-largest oil producer after the United States and Russia. It is also the largest producer in the Middle East and within OPEC, and boasts the world’s second-largest proven oil reserves after Venezuela.

Facts & figures

However, many may not know that Saudi Arabia has the world’s eighth-largest proven natural gas reserves, after Russia, Iran, Qatar, Turkmenistan, the U.S., China and Venezuela. It is also the ninth-largest gas producer, after the U.S., Russia, Iran, Qatar, China, Canada, Australia and Norway.

However, all the gas produced in the kingdom is consumed domestically, primarily for generating electricity, water desalination and as a feedstock for the petrochemical industry. All these uses are expected to grow rapidly as Saudi Arabia develops its industrial sector and pursues economic diversification.

Facts & figures

Petrochemical feedstocks

Petrochemicals, like ammonia, ethanol and benzene, are obtained from petroleum by refining. Their production requires carbon sources, like crude oil, natural gas, coal and biomass. These sources are referred to as “feedstocks,” which are subjected to industrial processing. The resulting materials are then used in other industries, including construction, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and packaging, among many others.

Riyadh has set ambitious targets for its gas sector. In its Vision 2030 program, which was announced in 2016, gas production is expected to double in the next 10 years, to 23 billion cubic feet per day. That would place Saudi Arabia among the world’s top three gas producers, putting it on par with Iran’s or Europe’s current output.

Furthermore, the country plans to start exporting natural gas for the first time in 2030. Saudi Aramco, the national oil company and the largest oil firm in the world (but a relatively marginal player in the gas market) is repositioning itself to become “the world’s preeminent integrated energy and chemicals company.” Central to that target is the development of a global gas portfolio.

Energy transition

Several drivers have shaped Saudi Arabia’s gas agenda. Chief among them is the need to free up more oil for exports. After all, oil is currently a more valuable commodity than gas. However, half of the oil used for power generation globally is consumed in the Middle East, and the lion’s share in Saudi Arabia (18 percent), according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). On a hot summer day, the kingdom can easily burn an additional 1 million barrels of crude oil per day to keep its air-conditioning units running – equivalent to Australia’s or Turkey’s total daily oil consumption in 2019.

For an economy so dependent on oil revenue, it makes much less sense to burn the resource domestically than to export it.

For an economy so dependent on oil revenue, it makes much less sense to burn the resource domestically than to export it, especially since Saudi Arabia sells oil at home for much less than it would on the international market. A 2016 study by Jadwa Investment found that in electricity generation, the Saudi government could save $71 for every barrel of crude oil it substitutes with the gas equivalent by 2030.

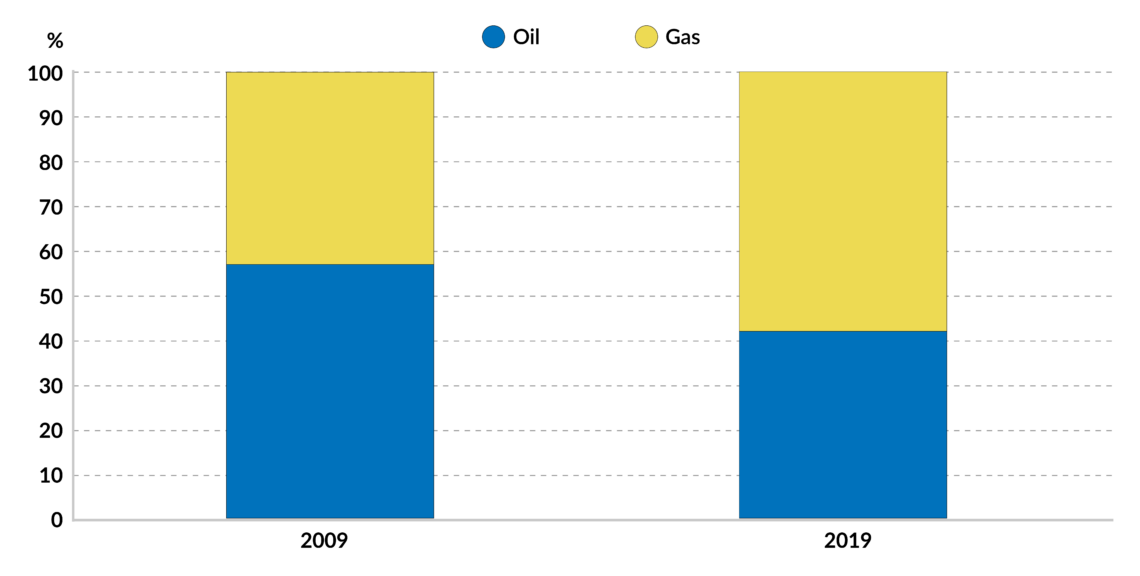

Natural gas already provides nearly 58 percent of the country’s electricity, with the rest coming largely from oil. Saudi Aramco aims to eliminate most oil burning for electricity generation by 2030.

Riyadh also recognizes the potential damage aggressive climate change policies can do to its fossil fuel business, mainly oil. As the energy transition accelerates, oil demand will shrink, pushing prices lower. Low-cost producers, like Saudi Arabia, will be the last to leave such a market. To protect its revenue, it must compete on volume sold internationally.

Facts & figures

Aramco says that by promoting the use of natural gas, it can help reduce the world’s carbon footprint. But the strategy is not just about saving the planet. Saudi Arabia wants to use gas to capitalize on the global energy transition. Natural gas is an important feedstock for petrochemicals, which the kingdom sees as a major pillar of its economic diversification. Also, gas can be used to produce hydrogen, an increasingly popular fuel for environmentally friendly technologies.

Breaking with tradition

To meet its ambitions, Saudi Arabia needs to produce a lot of gas. Its current output does not reflect its potential. For many years, most of its production was associated gas, a byproduct of oil extraction. How much gas it produces has therefore been dictated by decisions related to oil output. For instance, if OPEC agrees to cut oil production, associated gas production suffers.

To break that link, Saudi Arabia is turning to its nonassociated gas, both conventional and unconventional resources. Currently, about 57 percent of the country’s total production comes from nonassociated conventional gas.

Facts & figures

Oil and gas in Saudi Arabia

- The oil and gas sector accounts for nearly 50% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP and 70% of its export earnings (OPEC)

- About 60% of Saudi Arabia’s total gas production comes from four fields: Ghawar, Safaniya, Berri and Zuluf. Associated natural gas produced at the Ghawar Oil Field alone accounts for almost 50% of total production (EIA)

- Electricity demand increased by a compound average growth rate of 6% between 1990 and 2016 due to population growth and industrial sector development

- Iran, Qatar and Saudi Arabia are the three largest gas producers in the Middle East, accounting for 34%, 27% and 17% of the region’s output, respectively

- Saudi Arabia’s total proven natural gas reserves in 2019 stood at 237.4 Tcf, accounting for 18% of GCC reserves and 3% of the world’s (Saudi Aramco)

- Iran and Saudi Arabia are expected to account for 70% of the total consumption increase in the Middle East by 2025 (IEA)

Since the success of the shale revolution in the U.S., Saudi Aramco has been trying to exploit its own shale resources. In February 2020, it obtained regulatory approval to develop the Jafurah Basin, Saudi Arabia’s largest unconventional natural gas field, located in the country’s Eastern Province. Production from the field is expected to start in 2024. Some consider that time frame ambitious, even though the company plans to invest some $110 billion there. Back in 2012, the World Energy Council expected commercial shale production at the Jafurah Basin to start before 2020.

Shale exploration presents serious technical challenges, which is why it has so far largely remained restricted to the U.S. and, to a much lesser extent, Argentina. Shale extraction technology uses large quantities of water, a scarce resource in Saudi Arabia.

The question becomes whether Saudi Arabia would be better off importing gas than producing it domestically.

The technical challenges translate into higher costs. Here, the question becomes whether Saudi Arabia would be better off importing gas than producing it domestically. In its 2019 bond prospectus, Saudi Aramco stated that if domestic demand for gas grows beyond its planned production, it could “expand its gas operations, explore for new nonassociated gas reserves or pursue unconventional gas resources, such as shale gas.”

However, it noted that “[t]he cost of any of these alternatives could be significant, particularly for pursuing unconventional gas resources, which typically have higher exploration, production, and development costs than conventional gas resources.” It would therefore consider importing natural gas “if doing so is more economical than producing additional gas domestically.”

The cost difference could also explain the large disparity between Saudi Aramco’s production forecasts of 8.4 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) by 2030 and the IEA’s much more conservative estimate of 3.7 Tcf by 2025 and 5.6 Tcf by 2040.

Scenarios

To keep its options open, Saudi Aramco is looking at other opportunities, particularly importing liquefied natural gas (LNG). In 2019, it signed a preliminary contract with U.S. firm Sempra Energy to negotiate a 20-year LNG sale-and-purchase agreement from the Port Arthur LNG export project under development in Texas. The deal also included negotiations for Aramco to acquire a 25 percent equity investment in Phase 1 of Port Arthur LNG.

It would seem ironic for Saudi Arabia to import gas from as far away as the U.S. while Qatar, the world’s largest and cheapest LNG exporter, lies right next door. However, political tensions and a lack of intraregional gas trade infrastructure have prohibited cooperation between these neighbors.

Saudi Arabia has substantial natural gas resources and therefore significant potential to expand production capacity. Any increases in gas production, however, are likely to be absorbed by growing domestic demand, especially if gas entirely replaces oil in power generation. Exporting surplus gas is a goal that will have to wait a little longer.