Nicaragua’s sad and costly ‘stabilization’

Nine months since protests against worsening living conditions in Nicaragua began, the opposition is being terrorized and is less able to stage anti-government rallies. President Daniel Ortega’s prospects for hanging on to power are also uncertain: his government has few friends, and the country’s economic difficulties are mounting.

In a nutshell

- The Nicaraguan regime is ruthlessly trying to crush the opposition

- Only the U.S. continues to lean hard on Daniel Ortega’s regime

- Latin America’s second-poorest country is going into an economic tailspin

When I last wrote about the situation in Nicaragua, street protests against its increasingly dictatorial and kleptomaniac President Daniel Ortega – the former leftist guerrilla who helped overthrow dictator Anastasio Somoza in the 1970s – had shaken the regime. With the help of considerable outside pressure from the Organization of American States (OAS), the United Nations and the United States, the crisis appeared to have brought Mr. Ortega to the bargaining table to discuss ending the bloodshed, early elections and the restoration of civil rights.

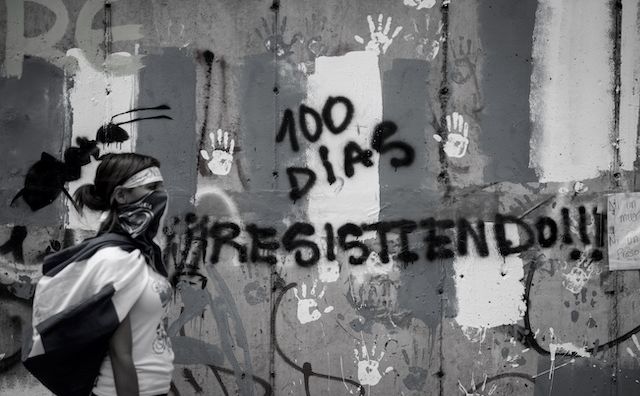

Since then, however, the president has raised the stakes by doubling down on the violent repression of all public manifestations of discontent, principally through the use of armed thugs known as turbas (or, more elegantly, parapolice), and arrests of suspected opponents.

Muffled protests

He has withdrawn the offer to negotiate his early departure and refused to allow a delegation from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to reenter the country. In his public addresses, he persistently brands all protesters as terrorists and all opponents as “golpistas” (those who want to carry out a coup d’etat). The bloodshed continues, albeit at a lower rate. By the count of the Nicaraguan Center for Human Rights, between the start of protests in April 2018 and mid-December, at least 322 Nicaraguans lost their lives (including 22 police officers and some 50 individuals associated with the government) and 565 were jailed. Also, thousands are reported injured by the police and the turbas.

While it would be an exaggeration, in continuing the poker metaphor, to say that the opposition and international community have folded and left the game, indeed it is true that the Nicaraguan opposition is no longer coherent nor is it able to mount protests of any kind with any regularity.

The U S. government has criticized the regime consistently and backed its words with some moves.

The country’s senior clergymen, who had joined the opposition in July when the Episcopal Conference of Nicaragua demanded Mr. Ortega’s resignation, have muffled their protests. The private sector, organized under the umbrella of the Superior Council for Private Enterprise (COSEP), has launched separate negotiations with the government to reestablish some form of dialogue. The OAS, for its part, has shot its bolt after a ringing vote of denunciation of the regime at the end of July, in which its Permanent Council called on Mr. Ortega to negotiate an early exit.

The U S. government has criticized the regime consistently and backed its words with some moves, such as the Treasury Department’s sanctions on Mr. Ortega’s wife and deputy, Vice President Rosario Murillo, and the presidential couple’s security advisor, accusing them of corruption and human rights abuses. More significantly, in December 2018 President Donald Trump signed the Nica Act, which calls for the executive branch to bar any loans or grants to Nicaragua by international agencies. The act stipulates that any U.S. aid to Nicaragua should be contingent upon moves to restore democracy.

It is important to note that the hostility to the Ortega regime in the U.S. government is fanned by Cuban-born lawmakers, such as Senators Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and Robert Menendez (he is now retired from the Senate). Perhaps as a reflection of that animus, National Security Advisor John Bolton and U.S. Vice President Mike Pence have spoken against Mr. Ortega in the context of suggesting U.S. military intervention again in the region. The U.S. has been careful to distance itself from the efforts of the OAS and UN to protect human rights or to bolster democracy in the three troubled countries.

Enter: the economy

If the Nicaraguan regime has indeed weathered the storm and solidified its control over the country, the price tag for the Central American nation to pay will be steep. Even before the protests began, it was the second-most impoverished country in Latin America (only Haiti is worse off). Thanks in large part to the efforts of COSEP, foreign investment began to pick up in the early years of this century, especially in tourism. Economic growth reached respectable levels before 2018.

Facts & figures

Nicaragua's GDP performance from 2014 through the first half of 2018

Now, however, the riots and violence have decimated the tourism industry. Foreign investment declined 90 percent between the first and second halves of 2018. The World Bank expects the Nicaraguan economy to have shrunk by nearly 6 percent for the year.

The state repression and the decline in basic public services such as hospitals and schools have accelerated the migration of Nicaraguans to other countries. Few if any Nicaraguans joined the famous Central American Caravan that has so bothered President Trump, although it is estimated that about a quarter of a million Nicaraguans have migrated north to the U.S. over the past two decades.

The most significant migration – more than 500,000 – has been to Costa Rica. Some Nicaraguans have applied for asylum there, overwhelming the government’s migration bureaucracy, while most simply melted into the broader population. The recent influx has put a severe strain on the new government of President Carlos Alvarado Quesada, which is also trying to cope with a gathering economic crisis and rising violence related to drug trafficking.

Remittances save the day

The exodus of more than 10 percent of the nation’s population brings a bit of good news. Those who settle in the U.S., Costa Rica or Panama (the third largest recipient of Nicaraguan refugees) send money back to friends and family. Over the past decade, remittances to Nicaragua totaled $12.5 billion. Compare this to the $3.7 billion in oil aid from Venezuela in the same period. The payments will allow tens of thousands of people to survive the difficult times. On the other hand, they dull the activist passion: as the government cuts back in financing social policies, the remittances help to ease the economic pain for many individuals.

Daniel Ortega is one of only a few heads of state in Latin America who have successfully withstood mass protests.

One of the unanticipated consequences of the disturbances over the past six months is that the controversial, Chinese-financed canal project (to rival the Panama Canal) has been canceled. This is bad news for the Ortega clan – the president’s oldest son was the CEO of the joint Chinese-Nicaraguan canal corporation – but good news for the indigenous peoples: the Rama Kriol, Rama and Miskito in the eastern part of the country. President Ortega never paid much attention to the east coast and even less to the indigenous peoples there. The young protesters and the more liberal, democratic wing of the ruling party had taken up their cause and that of the small Afro-Carib population on the Caribbean coast. At least that problem appears to be solved for the moment.

Scenarios

What will happen now? Can Daniel Ortega hold on to power? He is one of only a few heads of state in Latin America who have successfully withstood mass popular protests in the past three decades. In that same period, more than a dozen rulers in seven different countries have been forced from office by public anger. The key to the Nicaraguan president’s success thus far, aside from his unapologetic use of armed repression to put down the uprising, has been the inability of the protesters to organize into groups that might act through the political system to push the president out of office.

The international community, which appeared to take a stand in favor of early elections, now can only muster occasional calls for a dialogue between the opposition and the government.

In the next few months, the deteriorating economic situation, exacerbated by Venezuela’s inability to provide cheap oil and other aid, is likely to be the most potent force weakening President Ortega’s hold on power. His plan to have his wife succeed him as president may be a pipe dream now. The most optimistic scenario over the next few months is that Mr. Ortega decides to withdraw his money from the country and bail out. The Bishops’ Conference of Nicaragua-arranged Dialogue Table (Mesa de Dialogo) could serve as the cover for negotiations with the opposition. That might bring a less bloody end to the regime than any further public protests. For the moment, Mr. Ortega is firmly in control. His police continue to round up and incarcerate hundreds of suspected of opposition to his rule. In the first days of January, his thugs ransacked and closed the office of the popular opposition media company Confidencial.