A cautious global recovery

Oil markets are recovering thanks to OPEC+ production cuts, but they remain at the mercy of the global economy. Demand will need to increase well above the current levels to absorb the inventory buildup accumulated during the lockdowns.

In a nutshell

- Oil prices began to rise in May after production cuts

- They could begin to drop if the global economy is hit again

- OPEC+ set a price floor but demand will set the upper limit

This report is the first installment of a new monthly series on the latest developments in oil markets by GIS Expert Dr. Carole Nakhle.

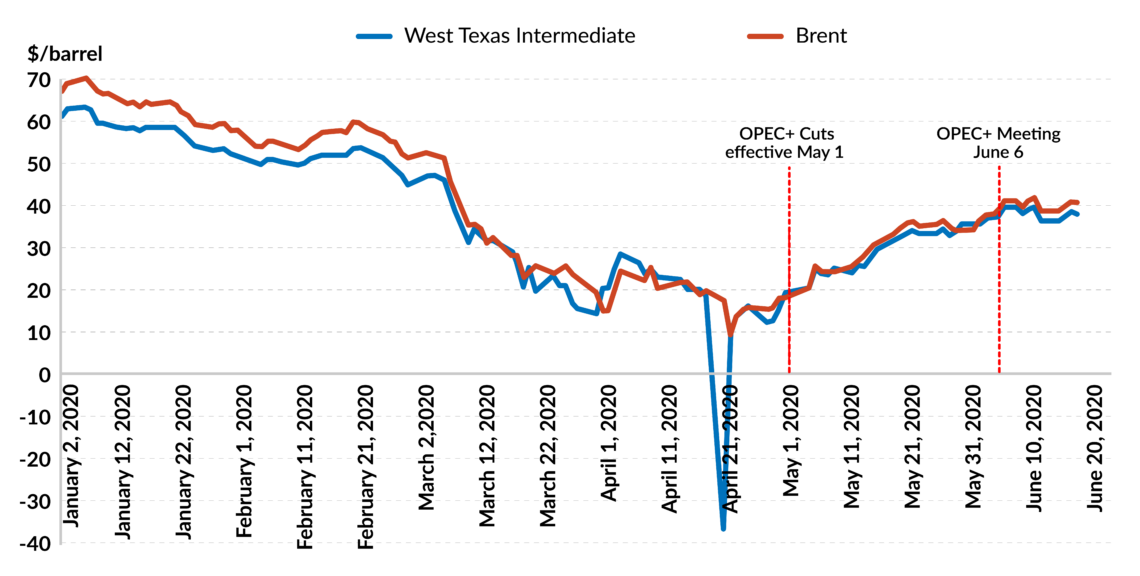

Most experts believe the worst is over for oil markets. Prices have gone up from the record lows reached in April. This recovery, however, is largely the result of production cuts – both voluntary, courtesy of OPEC+, and involuntary, courtesy of low oil prices – rather than a firm growth of global demand.

On balance, April will probably turn out to have been the worst month for oil markets this year. However, the prospect of recovery should be treated with caution; the dip was very deep and markets are rebooting from an extremely low point. OPEC+ efforts have raised prices. But this is proving difficult to maintain. In June, prices stopped increasing after a jump in May. It is still too early for the group to claim mission accomplished – any claim to success before 2021 is likely to be too early. To quote OPEC’s Secretary General, the oil markets are not “out of the woods” yet. The most important wild card for oil markets remains the health of the global economy, which in turn depends on the efforts to contain the spread of Covid-19. Here, uncertainty prevails.

Facts & figures

Oil after Covid-19

- The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects oil demand to grow by 5.7 mb/d next year. This would still be 2.4 mb/d below the 2019 level.

- On April 20, the price for West Texas Intermediate (WTI), a marker of U.S. crude, turned negative.

- By June 2020, the number of commercial flights worldwide reached 45,430, a 40% decrease since the beginning of the year.

- By May 2020, the cut in oil companies’ capital expenditures exceeded $85 billion.

- In 2019, China was the main driving force for energy, accounting for more than three-quarters of net global growth. India and Indonesia were the next largest contributors to growth, while the U.S. and Germany had the largest decline.

Stability

The oil market seems to be stabilizing. Prices are hovering around $40 per barrel – twice as much as in April, but still well below the levels recorded earlier in the year. Most estimates predict this situation will last at least until the end of the year. The United States Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts Brent to average $37 per barrel in the second half of 2020, rising to $48 per barrel in 2021. Similarly, in its June market update, Shell assumes a Brent price of $35 per barrel for 2020, rising to $40 per barrel in 2021 (in 2020 real terms).

The most important wild card for oil markets remains the health of the global economy.

However, several strong opposing forces are still at work. OPEC+’s deep production cuts appear to have created a price floor, but the upper limit continues to be set by oil demand, which is at the mercy of the global economy. The speed at which the record inventory buildup gets absorbed and a potential recovery in private production outside OPEC+ will also influence the market. For prices to rise significantly above current levels, demand needs to increase and supply will have to be restricted enough for the existing stock to be drawn upon.

Compliance

Rushing to the rescue of their economies, OPEC+ countries set a price floor and announced historic cuts of 9.7 million barrels per day (mb/d) as of May. These restrictions were supposed to last until June before being relaxed in July and then carried over to April 2022. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait also made additional voluntary cuts of 1(mb/d), 100,000 barrels per day (b/d) and 80,000 b/d respectively. On June 6, OPEC+ agreed to extend the output reductions by another month, until the end of July. The extension excludes Mexico, which decided to back out of the deal, bringing the total cuts to 9.6 mb/d.

As expected, not all members delivered on their promises. Typically, Iraq and Nigeria lagged behind. In May, OPEC’s compliance was 82 percent (87 percent for OPEC+), which is impressive given the organization’s lingering issues with members cheating. But under the current market conditions, for the measures to be effective compliance should be no less than 100 percent.

Facts & figures

In June, OPEC+ attempted to improve compliance by introducing a compensation system. Members unable to reach “full conformity” (100 percent) in May and June should “accommodate the underperformed volumes in July, August and September” and submit “specific compensation plans highlighting how this will be accommodated, and delivered,” the organization stated. The strategy seems to be working. Recent data indicates a significant improvement in member compliance for June (107 percent). The question is how long this discipline will last.

Private production

Outside OPEC+, the decline in oil prices led to a wave of production suspension – technically known as shut-ins. North America has witnessed the biggest decline in activity. The U.S. – with the largest number of well closures in history, especially in the shale basins – has been described as ground zero. This is unsurprising; shale oil is the first to leave the market in such situations because of its high responsiveness to prices.

Demand growth has been uneven across regions and countries.

The EIA estimates U.S. production will fall to 11.7 mb/d for the whole year, the first annual decline since 2016. In 2019, a record high of 12.23 mb/d had been reached. Between early March and early June, the U.S. also experienced the steepest weekly loss. However, by the end of June, oil production had rebounded by around half a million barrels to 11 mb/d. Though this is still well below precrisis levels, such an increase is not negligible. It is equivalent to the cuts that Iraq and Nigeria are yet to make to fully meet their commitment to the OPEC+ April deal.

Patchy growth

Oil demand destruction bottomed out in April and has been recovering as lockdowns ease. However, it is not expected to return to 2019 levels before the end of 2021, or more probably well into 2022. Overall, the year 2020 will see the largest decline in oil demand ever recorded.

Demand growth has been uneven across regions and countries. The lifting of restrictions has accelerated it; meanwhile the renewed spread of Covid-19 infections is decelerating it. The transport sector, worst hit by the lockdowns, is a good example of these opposing trends. Although traffic increased significantly once China eased its containment measures in May, the latest data shows a traffic decrease in major cities like Beijing and Shanghai after the government reimposed partial lockdowns. Air travel remains affected and is unlikely to return to pre-pandemic levels anytime soon.

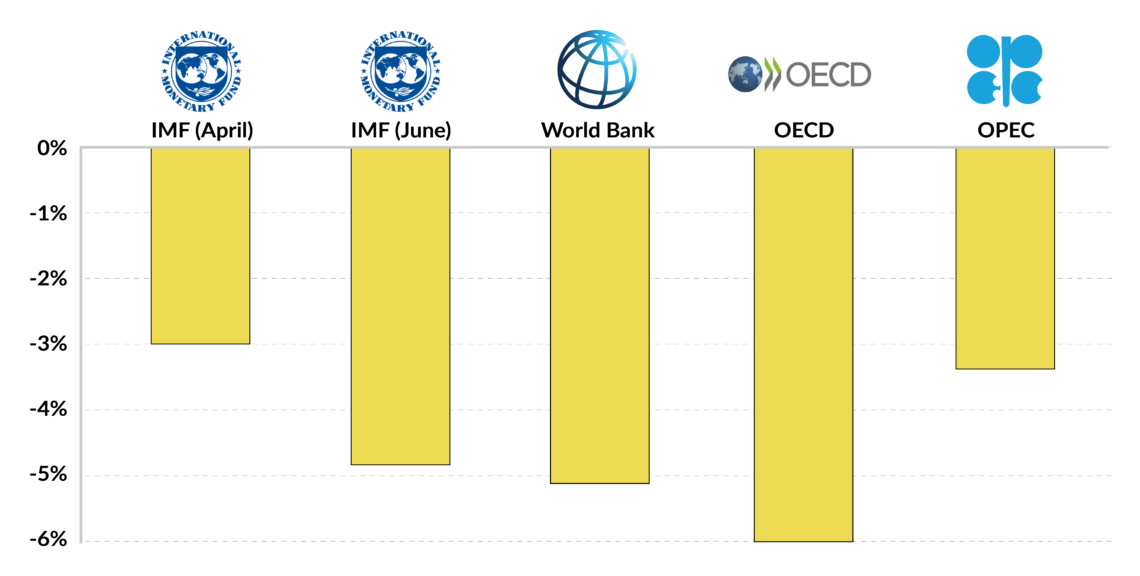

Price ceiling

For now, the most important factor continues to be the health of the global economy, which in turn is subject to countries’ effort to contain the spread of the virus. Forecasts of economic growth for this year are averaging between -5 and -6 percent. However, the energy community is more sanguine about the recovery, with OPEC expecting a contraction of only 3.4 percent.

Inventory buildup is substantial and demand is still fragile.

The latest International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecast was adjusted downward, with global growth projected at -4.9 percent in 2020, 1.9 percent below the April 2020 forecast. Initially, most forecasts assumed a V-shaped recovery, in which the economy returns to normal around midyear and then accelerates to reach pre-pandemic levels. While a V-shaped uptake is still possible, the latest forecasts predict it will begin later. In its June World Economic Outlook, the IMF expects recovery to be more gradual than previously thought.

Leading scientists continue to raise the alarm. “Clearly we are not in control right now,” disease researcher Dr. Anthony Fauci recently told the U.S. Senate. The Director General of the World Health Organization (WHO), Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, warned that “the hard reality is that this is not even close to being over… The worst is yet to come.”

Inventory buildup is substantial and demand is still fragile. For now, OPEC+ may have succeeded in setting a price floor. Oil demand, however, will continue to determine the ceiling.