Fiscal policy’s moment

The Covid-induced economic crisis has led policymakers to put in place large fiscal rescue packages. Governments will now be tempted to spend more to boost the recovery. Soon, however, countries will have to pay for the debt they have rung up in the pandemic.

In a nutshell

- Large stimulus efforts will leave countries with additional debt after the pandemic

- Tax increases will deepen and prolong the economic slowdown

- Reducing expenditures will set countries back on the right path

This report is part of a GIS series on the consequences of the COVID-19 coronavirus crisis. It looks beyond the short-term impact of the pandemic, instead examining the strategic geopolitical and economic effects that will inevitably be felt further in the future.

Global lockdowns imposed to limit the spread of the coronavirus have suspended activity throughout large swaths of the economy, reordered others and created deep and possibly lasting changes in peoples’ employment. Policymakers, believing they need to tackle the financial strain, proposed large fiscal packages of new spending, tax cuts, and subsidized loans to ailing industries. While the initial rescue packages are behind us, governments have two more crucial inflection points ahead that could determine the economic evolution of this crisis.

Pandemic fiscal policy will follow three stages, evolving differently across countries. The immediate convulsions that have resulted in large, new temporary safety-net programs to support distressed businesses and unemployed workers came first. As lockdowns end, the traditional calls for Keynesian stimulus spending to boost recovery will become louder, with politicians wanting to be seen as actively aiding the recovery. Finally, increased spending and depressed revenues will require fiscal adjustments in many countries – tax hikes, spending cuts, or some combination of both.

Higher levels of public spending and post-pandemic debt can crowd out private investment.

Economic research and historical experience provide clear predictions about how governments’ actions at each of these stages will affect the depth of each country’s recessions and the speed of the recovery. Moving forward, states that implement large spending stimulus programs, funded by new debt and future tax increases, will likely experience longer recessions and slower economic revival.

Supporting shuttered economies

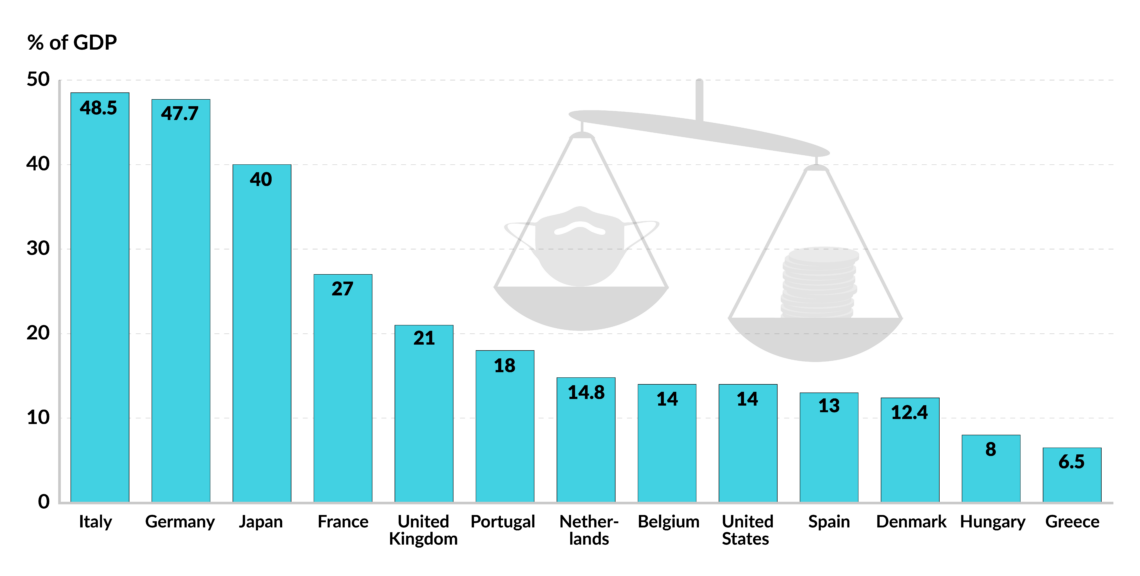

The initial aid provided by governments or available through programs that are designed to expand automatically in times of need, such as unemployment benefits, has served as a floor for the economy to rest on while “nonessential” functions are closed or reduced and the pandemic is tamed. In Germany, fiscal relief so far has totaled nearly 48 percent of the country’s 2019 gross domestic product (GDP), according to research firm Bruegel. The response includes 100 billion euros to buy stakes in struggling companies, billions more in grants to micro-businesses, expanded access to welfare payments, and tens of billions of euros in public investment projects.

Facts & figures

Italy is not far behind, implementing a fiscal response equal to 48.5 percent of GDP. Japan has reacted with a budgetary package that will equal nearly 40 percent of its economic output. Similar programs have been authorized in France, Denmark and the Netherlands, to name just a few. Each of these countries has also cut and deferred income, payroll and value-added taxes. The average size of fiscal packages adopted by 10 European countries, the United States, and the United Kingdom have so far averaged about 21 percent of the previous year’s GDP.

Pandemic spending provides a direct and immediate advantage to the recipients, but will also come with distortions and costs. Expanded unemployment benefits can create a more sluggish labor market, deepening the recession and delaying the recovery by slowing workers’ return to employment, especially if the expanded payments are more generous than precrisis wages – as they are in the U.S. Businesses receiving loans and other subsidies will face new government restrictions and public pressure against changing employment levels or other corporate management decisions necessary to retool for the postcrisis economy.

Higher levels of public spending and post-pandemic debt can also directly crowd out private investment. Greece, Italy, Portugal, France, Spain, Cyprus and Belgium will have debt-to-GDP levels above 100 percent in 2020, as projected by the European Commission.

These distorted incentives will accumulate to slow the recovery and depress necessary levels of innovation following the crisis. There will also be benefits to keeping businesses solvent and allowing people to stay home without fear of income loss during the height of the pandemic. In the coming years, we will learn the magnitude of the trade-offs between lavish financial support and long-term economic growth.

Stimulus and the recovery

The usual calls for more aggressive spending programs to restart faltering economies have predictably followed the economic damage from the coronavirus and the resulting shutdowns. The European Commission recently outlined 750 billion euros of additional spending and the lower chamber of the U.S. legislature passed an additional $3.4 trillion stimulus bill.

At its core, the choice of whether to use fiscal stimulus is one between private activity and government activity.

As governments switch from the safety net that allowed countries to shutter large sections of their economies to new policies designed to reactivate ailing industries and jump-start employment, policymakers should heed the failures of past stimulus efforts.

The Great Recession policies demonstrated the inability of government spending programs to boost private activity or increase total output. Government spending tends to displace existing projects and employment, rather than add to them – and there is evidence that high levels of government debt could make additional spending far more detrimental to recovery than similar spending under smaller debt loads.

The stimulus programs that governments around the world are currently considering will likely stunt the private sector recovery rather than boost it. Reviewing the last 10 years of fiscal research, economist Valerie A. Ramey summarized the results from a wide range of economic models, techniques, and time periods, using data from across the EU and around the world. Her research found that in most cases, government stimulus spending shrinks the private sector.

At its core, the choice of whether to use fiscal stimulus is one between private activity and government activity. By merely shifting private activities to government, stimulus spending does not create additional growth – it likely depresses it. The aid programs currently being considered and implemented around the world will have one legacy: larger debts and increasingly uncertain budgetary futures.

Future austerity

Following an unprecedented fiscal response from countries across the EU and around the world, public post-pandemic debt and deficits will become increasingly important.

Through early summer 2020, average debt-to-GDP levels in the euro area and the U.S. will rise above 100 percent. Eurozone deficits are projected to average 8.5 percent of GDP in 2020, while the U.S. is set to hit deficits equaling 17 percent of GDP. Additional stimulus proposals will widen these gaps even further.

Governments cannot spend their way back to economic prosperity.

Depressed revenues from still-rebounding economies and heightened spending portend systematically elevated deficits, especially in the countries hit hardest by the pandemic. Under elevated deficits, debt will continue to accumulate. Doing nothing to address large and rising debts is not an option for many countries, even if interest rates remain low.

Governments will be forced to either cut spending, increase taxes, or some combination of the two, and governments often turn to tax increases first. For example, the proposed 750 billion-euro European Commission stimulus plan includes new taxes on EU businesses’ profits, taxes on digital transactions, carbon taxes and a plastics tax.

Throughout history, politicians’ proclivity to spend now and tax later has provided countless examples of countries driven into crisis. The austerity that brings spending in line with revenues is never easy to implement or costless, but such fiscal adjustments become imminently necessary because unavoidable in the long run. Debt accumulation is not a sustainable solution to chronic overspending.

The fiscal adjustments that focus primarily on reducing expenditures tend to be most successful at rekindling economic growth while also lowering debt-to-GDP ratios. Conversely, relying on new or increased taxes to remedy fiscal imbalances deepens and prolongs economic recessions and usually fails to reduce debt-to-GDP. This is the conclusion of Alberto Alesina, Carlo Favero and Francesco Giavazzi’s 2019 book, Austerity: When It Works and When It Doesn’t, which summarizes the history of fiscal consolidations through case studies and an empirical investigation of 16 countries over three decades and 184 austerity plans.

Fiscal adjustments driven by spending cuts are not necessarily contractionary, as many traditional Keynesian economic models predict. Reducing government spending can restore confidence in the government’s fiscal capacity and reassure individuals and businesses that taxes will not have to increase to cover current expenditures.

Inflection points

The initial response to this unprecedented global pandemic is mostly behind us. The effectiveness of shutting down economic and social life to slow the spread of the virus, and the systems for temporary financial support, will be judged over the coming years. While the current crisis is unparalleled in modern times, the next two big economic policy inflection points do have precedent from which policymakers can learn.

Try as they might, governments cannot spend their way back to economic prosperity. Countries that embark on large stimulus efforts will likely be left with little more than additional public debt. How governments respond to those debts will also be important. Tax increases will deepen and prolong the economic slowdown, while the more politically challenging task of reducing expenditures will set countries back on the path toward a sustainable economic recovery.