Power games in the Balkans

With the European Union gradually walking back its promises to integrate the Western Balkans, the region has begun seeking other allies. Brussels has done little to stop the progress of China, Russia and Turkey in cultivating closer ties with Balkan countries.

In a nutshell

- A new EU accession round is less likely than ever

- China, Russia and Turkey hope to boost their influence

- Beijing could make headway if the EU does not react

The Balkans were first described as “Europe’s powder keg” before World War I, and the expression was commonly used again during the violent breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Later, commentators and politicians often used the moniker to highlight the dangerous nature of the conflicts at the borders of the European Union. At the time, the prevailing opinion was that only the integration of all southeastern European states into the EU and NATO could ensure lasting peace. In 2004, Slovenia joined the Union, then, in 2007 Bulgaria and Romania, and in 2013 Croatia. Since then, there has been no further expansion.

Incomplete enlargement

At the 2003 Thessaloniki summit, the EU heads of state promised the six countries of the Western Balkans (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia) the prospect of EU membership as the next major development goal. This “Thessaloniki promise” has been renewed several times, most recently on October 6, 2021, at the EU summit in Kranj, Slovenia. However, little progress has been made. Accession talks with Serbia and Montenegro are stalled, and they have yet to begin with Albania and North Macedonia. Bosnia and Herzegovina is still waiting for an invitation, as is Kosovo.

The EU and the Balkan states all regard accession as the only way forward. But the process has failed so far because of the EU’s growing skepticism about enlargement, because of the simmering conflicts between the Balkan countries themselves, and because of their failure to align with the Union’s legal framework.

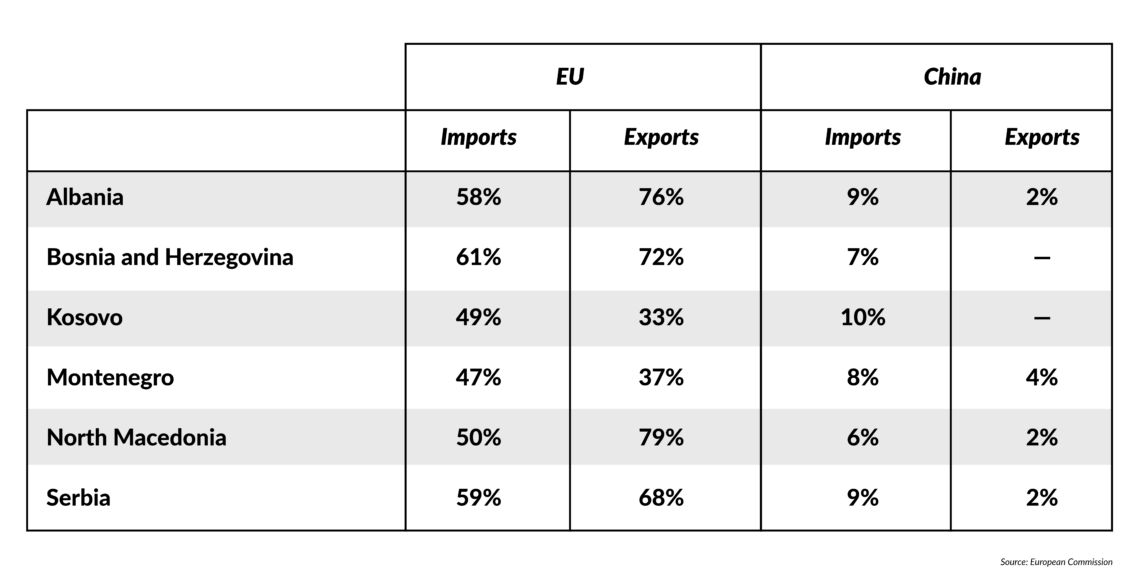

The EU is by far the most important trading partner and investor in the region.

The argument many in Brussels are making against admitting these countries is that the EU first has to absorb the previous accession process, which admitted 13 states. At the EU-Western Balkans summit in Kranj in October 2021, Germany and Austria, as well as the eastern and southeastern European countries had to push hard to have the term “enlargement” included in the final document. France was strongly against it, and the Netherlands and Denmark would have preferred using the term “European perspective” instead of committing to enlargement. Among other things, these countries fear that the region’s accession to the EU would accelerate mass migration to the West.

Economically, the Western Balkans are closely linked to the EU, which is by far the most important trading partner and investor in the region. The bloc will make a further 30 billion euros in funding available over the next seven years. However, as a result of the constant delays and the elusive convergence criteria, confidence is waning that EU accession is a real prospect. The more this impression solidifies, the weaker support for pro-European political forces becomes – and the greater the temptation for the region to play off rival powers against one another for its own benefit.

In the Balkans, it is not only shortcomings in the areas of rule of law, freedom of the media, protection of minorities and the fight against corruption and organized crime that are hampering the accession process. National conflicts weigh more heavily against them. Serbia refuses to recognize Kosovo as an independent state, as do five EU member states (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Romania and Slovakia). China and Russia support Serbia, while Turkey has diplomatic relations with Kosovo. Bulgaria, in turn, demands a declaration from North Macedonia that there is no Macedonian minority in Bulgaria and that Macedonian is not a language of its own, but only a Bulgarian dialect. Sofia’s veto against North Macedonia also blocks the start of accession negotiations with Albania, as the EU wants to give both countries the green light together.

In the 18 years since the Thessaloniki summit, it has become more difficult, not easier, to integrate the Western Balkans into the EU. This has geopolitical consequences because non-European actors are filling the power vacuum. Russia and Turkey have fought for supremacy in the Balkans for centuries and are now taking advantage of the EU’s apathy to increase their influence.

The third major power expanding its position in the region is China. The growing engagement of these three states also further complicates accession, because it favors Balkan politicians who model the Chinese, Russian and Turkish authoritarian and state capitalist model.

Russia

In the 19th century, Russia used the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the struggle for independence of the Balkan countries to its favor. The conflict culminated in the 1877 Russo-Turkish war. Turkey had to surrender areas in the Caucasus and the Balkans to Russia and grant independence to Bosnia, Montenegro, Romania and Serbia. The Serbian-Russian alliance played a role in the outbreak of World War I, but collapsed in the wake of the Russian Revolution when the Kingdom of Yugoslavia adopted an anti-Soviet stance.

Only after the collapse of Tito’s Yugoslavia in 1991 could Moscow seize new opportunities to exert its influence. Economically, it is helped by the region’s strong dependence on Russian natural gas and oil as well as Russian majority holdings in regional energy suppliers. Apart from the energy sector, however, Russia is much less present than the EU. Its economic influence is often overestimated. In Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia’s Republika Srpska in particular, the prevailing opinion is that Russia contributes more to economic development. This is in large part due to Russian involvement in the mass media, which stirs up anti-Western resentment.

Facts & figures

Western Balkans' trade in goods with the EU and China, as percentage of the total trade, 2019

Moscow cleverly uses the close ties of the Orthodox Balkan Slavs to Russia. The strategic aim of this influence is to stop the rapprochement between the Western Balkan states and the EU and NATO. In 2016, Russian agents orchestrated a coup attempt in Montenegro to prevent the small country from joining NATO. Russia also supports Serbian separatist efforts in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and in Kosovo. In the summer of 2021, the dispute between the Serbian Orthodox and the Montenegrin Orthodox Church over ownership of churches escalated in Montenegro. The Kremlin uses such conflicts to prevent the region from stabilizing.

Serbia is the closest Russian ally in the Western Balkans and the only country that does not seek NATO membership. In 2007, the Serbian parliament decided that the country would maintain military neutrality. Albania, Croatia and Montenegro are already in NATO. Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina want to join the alliance as soon as possible. The region is surrounded by NATO countries, on land by Slovenia, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Greece, and on the high seas by Italy.

Turkey

As the successor to the Ottoman Empire, Turkey relies on historical, cultural and religious ties to the Balkan Muslims, who mainly live in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia and the Sandzak region of Serbia.

Relations with the Albanian ethnic group are particularly close. On January 6, 2021, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan agreed on a “strategic partnership” to intensify cooperation at all levels. Unlike Russia, Turkey has recognized and supported the independence of Kosovo at the United Nations. On July 19, 2021, Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic reacted by stating that “Turkey is a great power, Erdogan is great, I am small and negligible, but Serbia is not so small that it would not attempt to stand up to that.”

In March 2021 there was a change of power in Kosovo. Prime Minister Hashim Thaci, a Turkish-friendly politician and personal friend of Mr. Erdogan, had to hand over his office to the nationalist Albin Kurti. Relations between Ankara and Muslims in the Western Balkans had deteriorated somewhat after the attempted coup in July 2016 when President Erdogan began to persecute the followers of cult leader Fethullah Gulen. To force their extradition to Turkey, he exerted massive pressure on the states of the region, where the Gulen movement had gained considerable influence.

Moscow cleverly uses the close ties of the Orthodox Balkan Slavs to Russia.

Turkey is competing with Saudi Arabia, whose involvement is increasing. Balkan Muslims are closer to the religiously moderate Turks than to the radical Saudi Wahhabis. The formation of Salafist communities supported by Riyadh was therefore followed with great suspicion in Ankara. Saudi Arabia is also an economic rival. To boost its precarious food supply, Saudi companies are buying large quantities of agricultural land and processing plants in the Balkans.

Politically, Riyadh’s influence is very small compared to Turkey’s. But President Erdogan’s chances of pushing through his “neo-Ottoman” project in the Balkans should not be overestimated either. Turkey’s great power ambitions, which extend from the Caucasus and the Middle East to the Western Mediterranean, do not match the possibilities of the economically ailing country.

China

The third major power intervening in the Balkans has no historical, religious or cultural ties to the region. Unlike Turkey and Russia, it does not rely on certain ethnic or religious affiliations, but offers itself to everyone as a partner. China does not attempt to thwart the rapprochement between the Western Balkans and the EU. On the contrary, Chinese leadership sees the Balkans as a bridge to the EU, their most important trading partner. Beijing hopes to expand its economic and political influence over Europe and create a positive image of China as an emerging great power. Commercial interest in the Balkan markets is secondary.

China’s financial backing for its geopolitical ambitions exceeds that of Russia and Turkey. But the share of direct investment from the EU in the region is at 70 percent, significantly higher than from China, which is less than six percent.

“Mask diplomacy” and the supply of Chinese vaccines to the Balkan states have improved the public’s perception of China, although the quality of the products supplied left a lot to be desired. China was quicker to deliver aid than the EU. “European solidarity does not exist … it’s only a fairy tale on paper, the only country that will help us is China,” said Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic in March 2020 when the EU banned the export of protective clothing.

With the exception of Kosovo, which has not yet been recognized by China out of consideration for Serbia, all Western Balkan countries take part in the 17+1 format operated by Beijing as well as in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The Greek port of Piraeus serves as a showcase project. The Chinese state-owned shipping line COSCO operates the port and is expanding it.

Like Russia, China is focused on Serbia. Since 2005, $10 billion in Chinese direct investments have flown into the Western Balkans. Struggling to receive EU funding for infrastructure projects, countries in the region have turned to Chinese loans.

Chinese investments are particularly popular because the lax transparency requirements allow local oligarchs to profit from the flow of money. The cooperation between Serbian and Chinese universities and the Confucius Institutes in Belgrade and Novi Sad has had some success in promoting Chinese state propaganda. Serbia is a growing hub of Chinese influence in the region.

The volume of BRI investments fell short of the recipient countries’ expectations.

However, Chinese ambitions have also met resistance. On one hand, this is because the volume of BRI investments fell short of the recipient countries’ expectations. On the other, as part of its anti-China strategy, the U.S. is warning the region against Chinese attempts to play American allies off against each other.

The China-financed Montenegrin highway from the port city of Bar to the Serbian border demonstrated how dangerous dependence can become. The cost of the project has risen to more than $1.3 billion, increasing the small country’s debt burden to 93 percent of GDP. Chinese banks account for 25 percent of the debt, which is guaranteed by the Montenegrin government. To avoid the debt trap, Podgorica was forced to raise taxes, freeze public sector salaries and cut social benefits.

Scenarios

Two scenarios are currently emerging:

In the first, the EU steps up its engagement in the Balkans, taking the “Thessaloniki promise” seriously and thereby reducing the influence of non-European powers. There is little to suggest that this could happen in the foreseeable future, unless new violent conflicts force EU intervention in the region.

In the second, China gains ground over Russia and Turkey, making the Balkans the flagship of its ambitions in Europe. This should arouse fears not only in Ankara and Moscow, but also in Brussels and especially in Washington.