A soft landing for China?

Despite outwardly positive indicators, China’s economy faces some troubling dynamics, from centralized decision-making to the overextended Belt and Road Initiative.

In a nutshell

- Financial authorities have manipulated markets and centralized policymaking

- China’s large economic presence throughout the Global South poses vulnerabilities

- Western investors have had plenty of reasons to avoid putting their money in China

At first blush, the Chinese economy is doing relatively well. Although annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 10 percent during the first decade of this century and dropped to about 7 percent during the next, it was remarkably strong during the pandemic and is expected to reach 5 percent this year. These are excellent figures compared to Western economies and the rest of the world, which have seen 2 percent and 3 percent GDP growth, respectively.

Consumer price inflation in China is around zero, the rate of unemployment is tolerable and the public debt-to-GDP ratio is close to or lower than that of all leading economies. And the real estate bubble has finally burst – good news, since the crash helps reduce some of the distortions that have characterized the Chinese economy for decades.

Given all this, why are markets watching what happens in Beijing with anxiety? The short answer is that observers believe that China is heading in the wrong direction and that its economy could soon get into serious trouble.

Causes for concern

China’s economic prospects face three issues. The first relates to its financial sector. Although some large Chinese companies are finally on the verge of collapse – and have stopped absorbing and squandering resources – the banks that financed them have now been refinanced by the central government (effectively a bailout). While some cleaning up is taking place in certain areas of the economy, further distortions have been piling up in others. More generally, it appears that when a crisis breaks out, Chinese authorities tend to intervene by manipulating financial markets and centralizing decision-making processes. As a result, the role of free-market mechanisms weakens, which does not bode well for future growth.

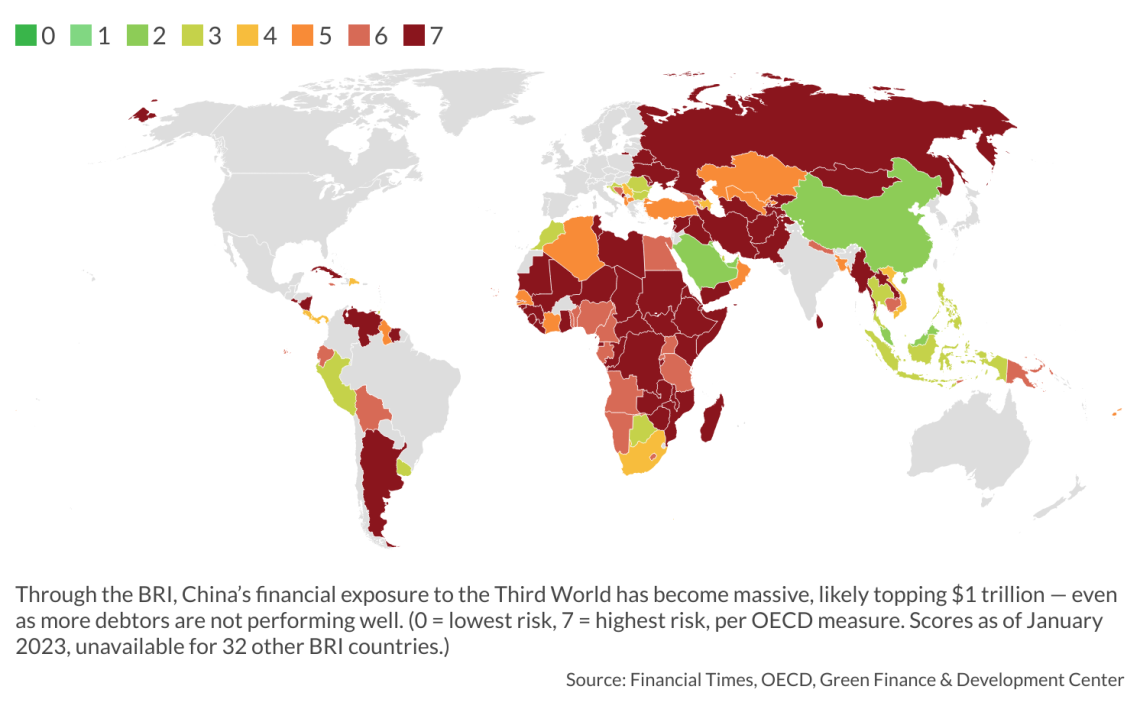

Second, China’s investment strategies driven by its geopolitical ambitions do not seem to be delivering according to plan. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is now a decade old, and it has failed to become a global project, with India and most Western European countries still on the outside, while Russia’s position remains unclear. Instead, the BRI has become an effort to claim Chinese leadership in the Third World by investing in large infrastructure projects and financing initiatives developed by member countries. So far, the returns on these investments are unimpressive.

Facts & figures

A Chinese presence in several key countries has certainly helped ensure that critical raw materials make their way back to the country, but there is no reason to think that China enjoys particularly low prices for those goods or that these flows will survive during a political crisis or military confrontation. Rather, the size of China’s financial exposure to the Third World has become massive (likely at least $1 trillion) and continues to grow, while suffering from more and more debtors underperforming. It is quite possible that China will lose a non-negligible share of these funds, that some of its infrastructure investments will turn out to be white elephants and that political tensions with troubled debtors will emerge.

Geopolitical tensions

The third dynamic involves the trade war between China and the United States, political tensions related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Beijing’s saber-rattling over Taiwan and the South China Sea and China’s recent drive toward centralized policymaking. Western companies in recent years are overall less than eager to invest in China, and many are trying to reduce their presence in the country. The consequences are perhaps moderate in the short term, but they may be significant in the long run.

Chinese central planners will probably encourage domestic investors (state-controlled companies) to step in, to ensure that the country’s production capacity expands and that adequate funds are made available to sustain technological progress in the absence of high-tech know-how coming from Western direct investment.

The misallocation of resources, along with the recent drive toward central planning, will likely lead to lower growth in the future.

Yet bureaucrats have always been inadequate substitutes for free-market investors and entrepreneurs. Technological progress and economic growth depend on several factors: the exchange of ideas; the right machines and equipment made by efficient producers; entrepreneurship, or the ability to take chances and transform ideas into productive ventures; and an institutional context in which entrepreneurs do not shy away from risk, can focus on productive ventures and are discouraged from sticking with failing projects. These qualities do not seem part of the strategy currently pursued by Chinese authorities.

China has ceased to be a land of opportunities and has turned into a source of instability – or, at least, a country to be avoided if geopolitical tensions intensify or for those who dislike interacting with a tightly controlled bureaucracy impervious to free-market principles. In other words, Western investors are more than justified in trying to reduce their exposure to China. Technological progress will not significantly slow down, but Chinese efforts to ensure that their advances keep up with or exceed the West’s will absorb resources that could be used in other areas. This misallocation of resources, along with the recent drive toward central planning, will likely lead to lower growth in the future.

Scenarios

Least likely: Reform in Beijing

In the least likely scenario, Beijing would have second thoughts and backtrack from its course of economic policy. The government would stop printing money and manipulating the credit market to the benefit of ailing banks, do what it takes to welcome back foreign investors and ensure that domestic entrepreneurs focus on productive and competitive activities, rather than schmoozing with policymakers. Moreover, it would recognize that the financial component of the BRI has been a flop and would take steps to restructure debtors’ positions on very generous terms.

Less likely: Damage control

Another unlikely scenario would see Chinese actions targeted at reassuring Western investors, while still sticking to the strict regulation of domestic firms and heavy interference in the financial sector. This would be a lengthy process, and results would be far from guaranteed. Beijing would have to make clear that it will not attack Taiwan, but will engage in at least partial and possibly unilateral trade liberalization and revise its traditionally complex and erratic set of rules applying to foreign investors. This is not easy; it takes time to win back trust once you have lost it. What’s more, China is not as attractive as in the past: prospects for economic growth are not stellar, the workforce is not as cheap as it once was and the quality of the output produced by domestic competitors has improved significantly, as some Western car producers have witnessed.

More likely: Centralized management

The most likely scenario is consistency with the recent approach: centralized economic management aiming at avoiding a major banking crisis. There would also be a more pronounced propensity to allow selected companies to go broke, especially if their owners stand a chance at challenging the political elites in Beijing. New campaigns against “corruption” and possibly “incompetence” may be around the corner. At the same time, we can expect renewed efforts to collectively replace the U.S. as the single greatest export market for Chinese products. This drive has already generated excellent results in the ASEAN region and Europe, and recent attempts to improve relations with Japan and boost trade with Latin America point in the same direction.

The West has two options within this framework. It can put aside trade barriers between developing countries, thereby raising the costs for China’s drift toward central planning and undermining Beijing’s efforts to revive or expand the BRI. Western governments can also try to stifle China’s efforts to bridge technological gaps by shelving their crusades against big business, especially in the high-tech sector.

However, there are no signs that Washington or Brussels intend to follow this approach. As a result, despite its current difficulties and increasing geopolitical tensions, China will likely manage to have its soft landing.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.