This ‘soft landing’ means stagflation

Having mismanaged the economies and now misrepresenting the problem, central bankers and politicians in the West pray for a “soft landing” instead of a recession.

In a nutshell

- Irresponsible policies are catching up with Western economies

- The central banks and political leaders deny their responsibility

- Instead of a “soft landing” a full-bore recession may come next

The figures and predictions about the world economy are not catastrophic but remain disappointing. Politicians and central bankers were expecting and had promised all but stellar performances after the end of Covid-related restrictions. In their view, years of monetary and fiscal profligacy had been a success story. A future of sustained growth and 2 percent inflation would have paved the way for the “challenge” and the business of the 21st century: the war on climate change. However, to the world leaders’ surprise, they had to revise their macroeconomic predictions for the next years and put the fight against climate change on hold. These days, the buzzword is “soft landing” – trying to assure that the economic slowdown does not lead to a full-blown recession.

Foggy prospects

No one ventures forecasts about the long run. The available predictions only cover the next couple of years: the United States’ gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to grow by about 1.7 percent in 2022, 0.5 percent in 2023 and possibly lower in 2024. A recession, “most unlikely” to the policymakers until a couple of months ago, has become “possible.”

The data for the European Union is similar. Indeed, the optimistic fanfare of 2021 has been quickly forgotten.

The prospects for China look better: growth should be about 4 percent in 2022 and one percentage point higher next year. Yet, the figures remain well below the country’s past performances and will surely miss the “above 6 percent” target Beijing announced last January and reduced to 5.5 percent in early March. Not surprisingly, China’s central bank is currently injecting new liquidity into the system to avert a deeper slowdown.

The World Bank effectively summarized the situation in its June report, according to which world economic growth will drop from 5.7 percent (2021) to 2.9 percent (2022). The January prediction for 2022 was 4.1 percent. The toll is particularly heavy for the developing countries, which are growing at five percentage points below their pre-Covid trend.

Policymakers currently blame supply-chain bottlenecks and the Russian invasion of Ukraine for high inflation and weak growth. The explanation is doubtful.

Of course, this broad picture does not consider the effects of the anti-inflationary measures that may be belatedly undertaken during the next few months. Nobody knows what will happen: after celebrating their “forward guidance” policy (the central bank’s communication on the state of the economy and the likely future course of monetary policy) for about a decade, central bankers suddenly have become silent. Recently, European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said that forward guidance would be abandoned – for lack of credibility, one should add.

What went wrong

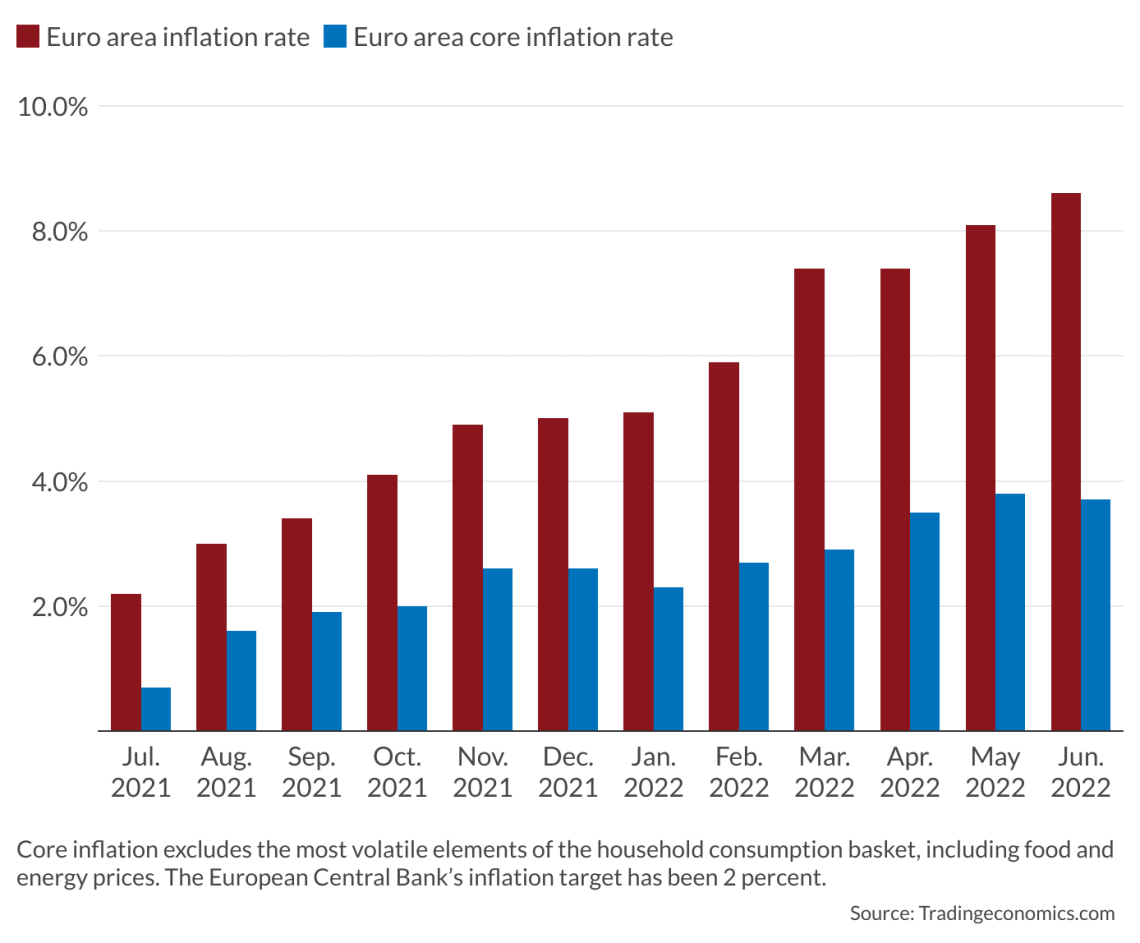

Policymakers currently blame supply-chain bottlenecks and the Russian invasion of Ukraine for high inflation and weak growth. The explanation is doubtful: bottlenecks were much tighter in the past three years than nowadays and will ease further in the future. This narrative provides a poor explanation for the troubles.

Facts & figures

Moreover, and in contrast with the central bankers’ narrative, slow growth and high inflation are neither unexpected nor temporary. The authorities manipulated the money and credit markets and, for over a decade, engaged in fiscal profligacy of major proportions. Countries worldwide – and the West in particular – have expanded the size of government and are involved in global regulatory exercises that have preserved poorly-run companies from going bankrupt or being taken over by more efficient competitors.

More on monetary policy by Elisabeth Krecke:

Zombies and stagflation: Draghi’s crisis prescription

The ECB and bringing financial markets down to earth

The governments dampened entrepreneurial spirit and encouraged the business world to engage in investment projects that would not have materialized without negative interest rates and significant subsidies. Not surprisingly, monetary and fiscal profligacy led to inflation, while modest labor productivity rises and relentless regulatory activity led to disappointingly low growth.

The distortions have lasted for a surprisingly long time, so many “experts” maintained that negative interest rates and hyper-regulation could be the ultimate cure-all. The world is now getting closer to what good economics suggests rather than uncharted waters.

Soft landing pretense

The critical question, therefore, is what policymakers are likely to do. Declaring that the name of the game is now soft landing is hot air: you cannot broach the landing issue unless you know where you are coming from and where you want to arrive.

Central bankers say nothing about what they would do if inflation persisted, and growth slowed further.

In fact, on both sides of the Atlantic, the target changes constantly. A few months ago, central bankers aimed to bring inflation down to 2 percent within a year while maintaining a relatively strong growth track. Then, the goal switched to getting inflation down to tolerable levels relatively soon while minimizing the deviation from the previous growth objectives.

More recently, professional politicians have abstained from making promises. The central bankers have clarified that monetary policy will consider the effects on the real economy but that they cannot exclude temporary recession. Of course, this says nothing about what they would do if inflation persisted, and growth slowed further.

Scenarios

Against this background, two scenarios open for the U.S. and the eurozone, the only big players where leaders resort to the soft-landing rhetoric. The first assumes the central bankers have no real strategy but stick to the claim that slow growth and high inflation originate from accidental supply problems.

Losing steam

Consistent with this view, the solution consists of cooling demand to take the air out of the inflationary process and forgetting about supply, which is supposed to be a mere transitory source of problems. Thus, monetary policy will become tighter – which is different from tight– if the supply problems persist. However, it will remain generous enough to avoid a dramatic crisis or exceedingly noisy discontent. In other words, central bankers hope to move from “temporary inflation” and “unexpected accidents” to “controlled and temporary stagflation.”

Unsurprisingly, these rather loose guidelines fit the politicians’ agenda, as they are shielded from the blame for the disappointing performance. If the geopolitical tensions ease and supply chains improve but growth remains weak, the political class could still point their fingers at the central bankers who engaged in allegedly rash monetary tightening policy driven by panic and poor forecasting in the summer of 2022. Moreover, a central banker who pretends that his or her monetary policy mistakes have nothing to do with today’s problems is also a central banker ready to support and monetize new efforts to stimulate aggregate demand and regulatory activities.

And this is the most likely scenario, unfortunately. It will saddle the Western economies with low growth, possibly reaching zero or negative values in some quarters. They will call it a soft landing: falling from 2 percent growth to around zero on an annual basis is not a crash, especially if pundits and public opinion expect it and the fragile public-debt situation in some countries does not shake the eurozone’s foundations too badly. This explains why the ECB recently introduced the anti-fragmentation/anti-spread tool, pompously announced as the “Transmission Protection Instrument” – and more aptly nicknamed, “To Protect Italy.”

There would not be much to celebrate, in any case. The West is losing steam: its current policies are miring it in a future dominated by stagflation. In most countries, technological progress may avert the worst, but economic growth will peter out if entrepreneurial efforts and managerial efficiency remain in short supply.

Hard landing

A second scenario stems from the assumption that the central bankers change their approach and find the will to confront the politicians, ending the history of unholy collusion. In such a situation (unlikely anytime soon), the data persuades the monetary authorities that inflation is indeed the priority; that the market should determine interest rates, and that a significant portion of the safety net currently protecting the depositors, commercial banks and governments should be removed. If that were to happen, and if the authorities accepted the fall of many unprofitable companies, the crash would inevitably follow but would also open better prospects for the future.

Either way, macroeconomic eyewash cannot change the simple fact that there are no free lunches. Someone will pay dearly for the flood of broken promises, stretched rules, bad policies and fanciful theorizing.