Sudan nears another breaking point

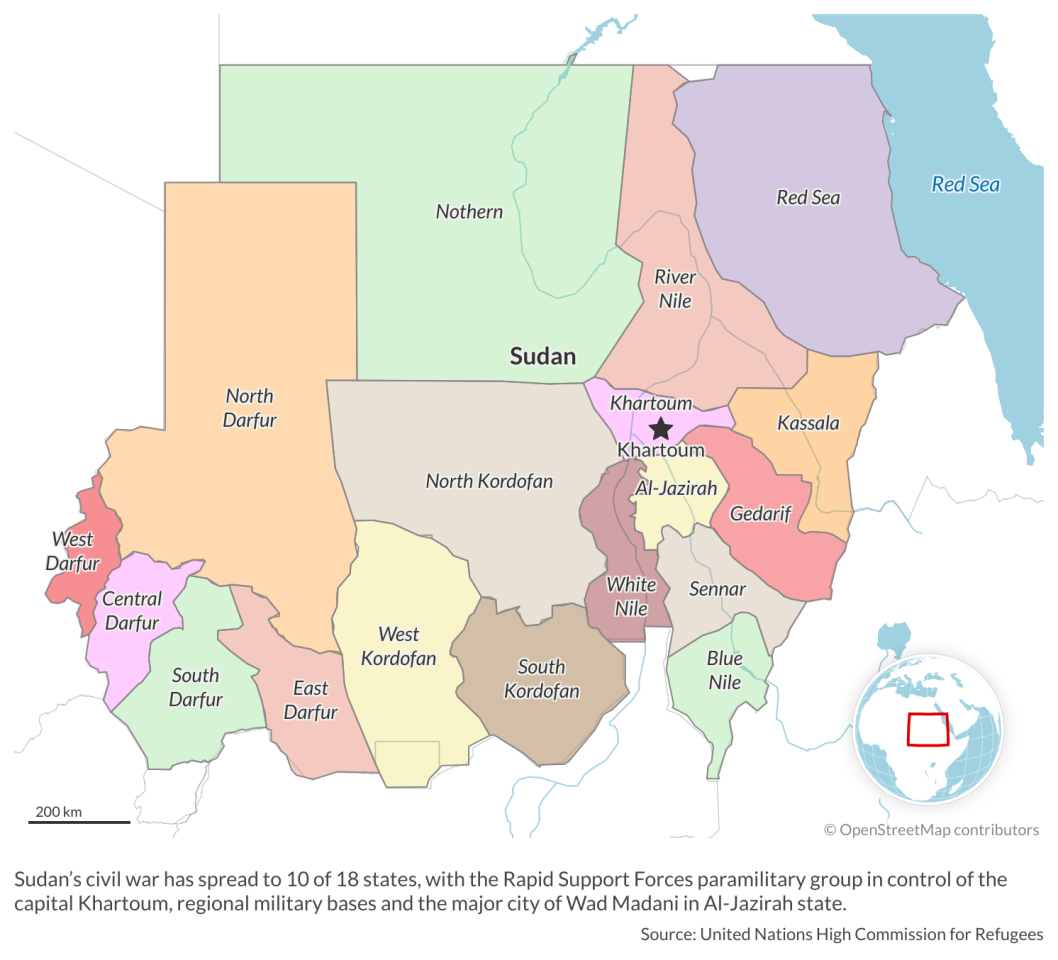

The civil war in Sudan that erupted in April 2023 is spreading. With thousands killed and millions displaced, the troubled nation is in danger of further fragmentation.

In a nutshell

- The 2019 ouster of Omar al-Bashir triggered an ongoing power struggle

- Civil war is spreading and reigniting ethnic violence throughout Sudan

- Fighting is likely to continue, fueling a growing regional crisis

Nine months after clashes broke out between the Sudanese military and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group, there is no solution in sight for the civil war in Sudan. The armed conflict has already killed at least 12,000 people and displaced seven million others in the northeast African nation of 45 million people.

The end of the 30-year regime of Omar al-Bashir – deposed after a 2019 coup in which the RSF participated – did not pave the way for democratization. Instead, it set the stage for conflict between two strongmen.

The official Sudanese military is led by the nation’s actual ruler, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, while the RSF is commanded by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemedti. The two men joined forces to stage another coup in 2021 that removed a civilian government two years after the ouster of Mr. al-Bashir. But now the two are fighting each other for control of the nation.

The war has spread to 10 of Sudan’s 18 states, further destabilizing a country that is already suffering from violence, displacement and poverty. On December 19, 2023, the RSF took over Wad Madani, the capital of Al Jazirah state.

More by Teresa Noguiera Pinto

Somalia at a critical juncture

Debt-crushed Ghana is turning volatile

Deepening dysfunction in Zimbabwe

Violence escalates in many regions

The renewed violence kicked off on April 15, 2023, with clashes between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF in Khartoum, the capital. However, the unrest has since expanded into other states, including South and Central Darfur and South Kordofan. The escalation exposes old and new cleavages between Arabs and Africans, Muslims and Christians, semi-nomadic pastoralists and agriculturalists.

These social divisions have spurred killing among warring factions and reignited ethnic violence as militias and local self-defense groups join in the fight. Moreover, competition for resources and strategic routes in the Darfur region and the Red Sea state is becoming intense. In Khartoum, the RSF controls critical areas, while the SAF has intensified airstrikes against the RSF strongholds.

The RSF has also secured at least four regional military bases. In June, the governor of West Darfur was kidnapped and killed after he denounced killings of civilians by the RSF and requested foreign intervention. Several villages in the region have been attacked. In November, between 800 and 1,200 people were slaughtered in Ardamata, close to the border with Chad, by the RSF and the Janjaweed Arab militias. The massacre, targeting the members of the non-Arab Masalit group, is another sign of an upsurge of ethnic violence in West Darfur.

Like in Darfur, the last five decades in South Kordofan state, which borders South Sudan, were marked by ethnic tensions and insurgency as rebel groups questioned the legitimacy of the Khartoum-based government. Clashes still routinely take place between the SAF and a faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), and between rival ethnic militias. Resistance to the Sudanese regime is strong in the Nuba Mountains.

Violence has also erupted in the north, particularly in the Red Sea state. The city of Port Sudan is a key logistics hub located on Sudan’s Red Sea coast. It is also an operational base and recruitment center for the SAF. In September, the Sudanese Armed Forces clashed with local militias, which, despite opposing the RSF, do not welcome the army’s presence in the area, as they fear losing power and access to strategic routes and resources.

Facts & figures

Sudan’s major upheavals since 2019

Sudan formally achieved its independence from Britain and Egypt on January 1, 1956. Since then, it has suffered numerous coups, uprisings and attempted coups. Among them since 2019:

April 11, 2019: After 30 years of rule, President Omar al-Bashir is overthrown by the Sudanese Armed Forces after popular protests demanded his ouster.

October 25, 2021: General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan staged a military coup in Sudan against the civilian leadership with the help of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group.

January 2, 2022: Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok resigns. Gen. al-Burhan seizes power in the country.

April 15, 2023: An armed conflict between rival factions of the military, the Sudanese Armed Forces and the RSF, starts with clashes in the capital, Khartoum, and the Darfur region.

Mediation efforts

So far, multiple mediation efforts by various actors have failed. Both sides have repeatedly violated cease-fire agreements. In December 2023, the United Nations Security Council decided to terminate the UN’s Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS). The shutdown of the mission, which was established in 2020 and employed 400 civilians, is another indication of the UN’s failure to tackle political and security challenges across the continent.

At this point, though, two mediation initiatives have gained some momentum.

The United States and Saudi Arabia have managed to convene the parties for talks in Jeddah with the Intergovernmental Authority for Development in the Horn of Africa. The African Union has also joined the process. While both sides, the SAF and the RSF, agreed to resume talks in late October, their participation has not changed the situation on the ground. Neither of the warring sides – and particularly the RSF – sees a cease-fire as advantageous. However, the Sudan Tribune reported on January 3, 2024, that Hemedti, the RSF commander, is calling for a comprehensive peace agreement.

The Red Sea has become a critical point of Saudi Arabia’s security strategy. Nonetheless, stability in the region is now compromised by the revival of the Houthi militias following the October 7, 2023, Hamas attack against Israel, the agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland and the ongoing war in Sudan.

President of South Sudan Salva Kiir Mayardit, who recently assumed the chairmanship of the East African Community, is also pushing for a negotiated solution. The economy of South Sudan, which seceded from Sudan in 2011, is highly dependent on oil, which accounts for around 90 percent of revenues. However, the conflict has made it difficult to import chemicals required for oil extraction, while violence has disrupted export routes through Sudan. Moreover, the northern region of South Sudan relies on supplies that come from Sudan, and the conflict is damaging its local economy.

The Sudanese army, which counts on discreet support of Egypt, has accused the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Russia’s Wagner mercenary group of providing arms to the RSF. Recently, protests erupted in Port Sudan, demanding the expulsion of the UAE ambassador. In 2022, a consortium led by an Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund signed a $6 billion deal with the Sudanese government to build a port and develop an economic zone north of Port Sudan. The project is now in danger, as the SAF accuses the UAE of supporting the RSF and fueling the conflict.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

More likely: A long civil war deepens the economic and refugee crises

As anticipated in this author’s previous report on Sudan, the conflict looks set to continue. Neither side can claim a decisive military victory and there are no incentives to find a negotiated solution. Also, violence predictably has escalated in the Darfur region over the past months, and more armed groups, driven by different resentments and goals, have joined the fray.

Considering the current context, the most likely scenario is destabilization in the region and further violence and fragmentation in Sudan caused by the formation of civilian defense groups, the increasing presence of mercenaries and a growing outflow of refugees into neighboring countries.

The exodus into neighboring Chad is expected to continue. The refugee population in Chad, where 2.1 million people already face acute food insecurity, has dramatically increased in recent months. For South Sudan, the scenario of a prolonged conflict would severely damage its already fragile economy and be politically destabilizing.

Fragmentation, or the Libyan scenario, has become more likely. While the SAF is consolidating its control over Port Sudan, the RSF is in control of military bases and key regions, including Al-Jazirah, the country’s breadbasket. Despite calls for a cease-fire, Hemedti’s strategic advantage and his recent African tour suggest that the RSF leader has ruling ambitions and is seeking international recognition.

Less likely: The conflict becomes a proxy war

Under a second and less likely scenario, the conflict in Sudan could become a proxy war between regional powers. This could be triggered by an escalation of violence in Port Sudan amid rising tensions in the Red Sea region.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.