Debt-crushed Ghana is turning volatile

Ghana, one of Africa’s most democratic and fastest-growing states, has been backsliding into turmoil caused by its external debt and the rising costs of living.

In a nutshell

- Ghana’s high growth has been overly dependent on external financing

- The explosion of debt in 2020 disrupted the positive economic trajectory

- Its democracy is tested as anti-graft and cost-of-living protests are spreading

With a stable and functioning democracy in place since the 1990s and record-high economic growth rates in the 2000s, Ghana is often cited as an example of political and economic success. However, amid the risk of debt default only prevented by an International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan, with the national currency among the region’s worst performers and inflation spiking to 40 percent, angry popular protests have begun.

While Ghana has faced situations of unsustainable debt before (it is the 17th time since independence that the country has sought IMF relief), and there is a strong tradition of civic activism and mobilization among students and unions, this current wave of protests may signal a more profound malaise for which there is no easy cure.

A vicious cycle

In the late 2010s, Ghana was a rising star despite shocks caused by the commodities crash. One of the “African lions,” it was among the world’s fastest-growing countries in 2019. Its economy was diversifying, and income levels were growing while poverty decreased.

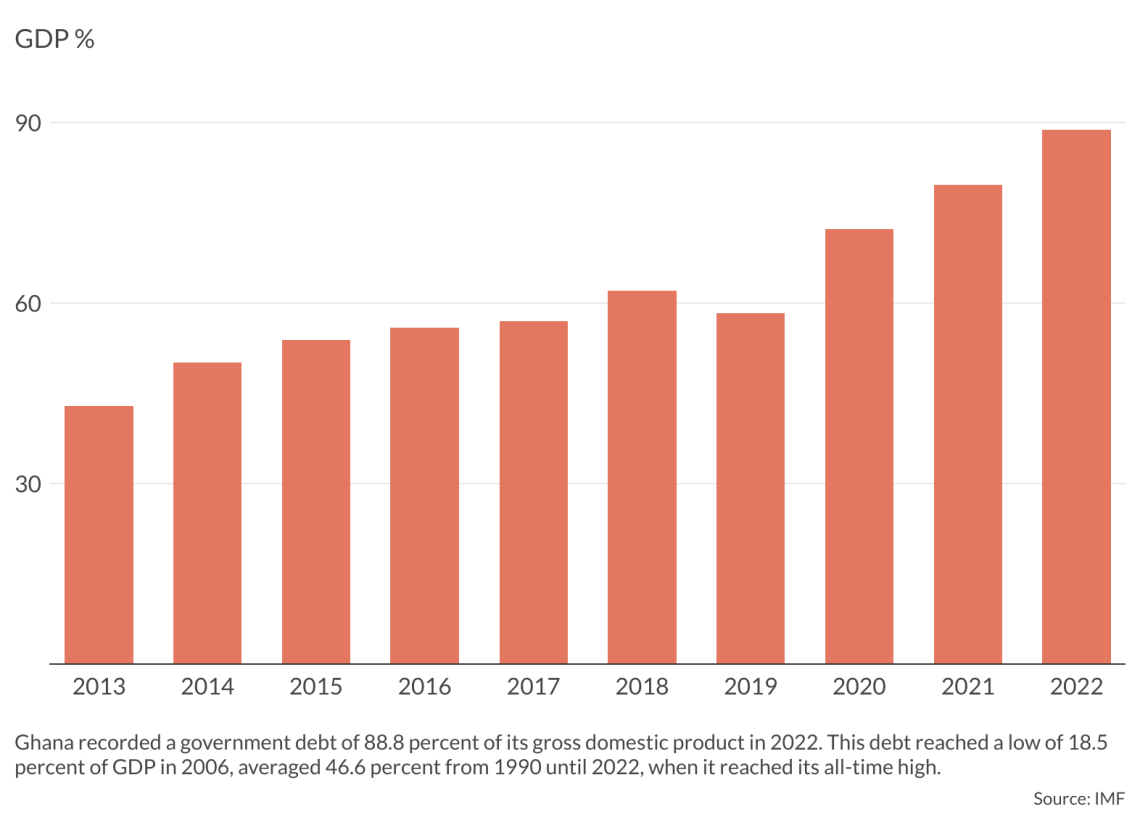

Undoubtedly, the roots of Ghana’s economic crisis today precede 2020, as cyclical shocks exposed its dependency on cocoa and gold exports and on external financing. But more recently, the Ghanaian economy fell victim to the costs of the dramatic measures imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic. As in other countries around the world, public debt has ballooned, reaching unsustainable levels. That, combined with anemic growth, inflation and unemployment is eating into gains made during the previous period.

Ghana was forced to seek, once again, help from the IMF in 2023. Its negotiated $3 billion relief package demands that the country restore macroeconomic stability.

Ghana also shows the failure of the IMF’s 1996 Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, which was designed “to ensure that no poor country faces an unmanageable debt burden.” Ghana joined the HIPC, but its debt has been expanding since 2006. Today, it stands at around 105 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), placing the country among the most indebted in Africa. Shrinking foreign currency reserves and about 70 percent of government revenue devoted to interest payments have combined for an unsustainable situation. Ghana was forced to seek, once again, help from the IMF in 2023. Its negotiated $3 billion relief package demands that the country restructure its public debt.

Inflation, the elimination of fuel and electricity subsidies, rising income taxes and the introduction of new levies on cigarettes, sweet drinks, mobile money transactions and a “Covid-19 recovery contribution” surcharge are fueling discontent among the working poor and the middle class. To tackle debt sustainability, the government ventured to reduce Ghana’s debt-to-GDP ratio from 105 percent to 55 percent by end-2028. It hopes to meet this seemingly improbable target by boosting revenue (which includes increasing the tax burden) and cutting public spending drastically.

Problem of leadership quality returns

Ghana has long been regarded an example of a thriving Western-style, multi-party democracy. Indeed, since it transitioned to democracy in the 1990s, the country has featured regular, free and fair elections, freedom of expression and a robust civil society.

Unlike many African regimes with personalized leadership or hegemonic parties, power in Ghana has alternated between the (now ruling) New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the National Democratic Congress (NDC). The pluralistic civil society and strong institutions, including a constitution that establishes political rights and civil liberties, are among the pillars of the country’s democratic superstructure.

Read more on Africa’s economic issues

Africa’s window of opportunity on trade

However, time and again, democracy proves to be a fragile endeavor. Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo, a member of the NPP, has served since 2017. Elected on the promise of crushing corruption, he secured a second term in 2020, but the opposition rejected the results and ensuing violence broke the cycle of nearly three decades of electoral stability.

Since that time, government members have been involved in corruption scandals, including the “Sputnik deal” (the purchase of Covid-19 vaccines from Russia) and the “contracts for sale” case, which led to the trial of the chief executive of the public procurement authority. Recently, the minister for sanitation and water resources was ousted and detained after it became known that members of her house staff had stolen more than $1 million in cash she had stashed in her bedroom.

Economic turmoil in Ghana after years of record-high growth is also attributable to the unending expansion of the public sector.

This activity, for the most part, is taking place inside the bubble of the country’s ruling establishment. And as protesters denounce perceived “moral decay” of the political system, there are signs that in Ghana, as elsewhere on the continent, a deepening disconnect has emerged between the agendas of legacy political parties and the aspirations of the generations born and raised after independence. When parties’ role as gatekeepers of the political system – that is, filtering, absorbing and responding to citizens’ demands – weakens, instability and disruption likely follow.

Economic turmoil in Ghana after years of record-high growth is also attributable to the unending expansion of the public sector – a trend hardly unique to Ghana. The pandemic-related shutdowns also have played a role. Whereas, due to its youthful demographic profile, Covid-19 was not a significant health threat in Ghana, the economic costs of pandemic mitigation efforts have been severe. The 2020-2021 disruption is going to have a long-lasting, harmful impact on many Ghanaians’ lives.

Ghana’s travails also expose the failure of the debt-burden moderation model in place over recent decades. Despite high growth rates, its economy, like other economies on the continent, has remained structurally dependent on external borrowing. This setup is unsustainable. Alarmingly, in a world where multilateralism is in crisis, reaching agreements with an increasingly diverse pool of creditors becomes more challenging.

Scenarios

Presently, the Ghanaian government finds itself between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, with elections scheduled for 2024, it has no incentives for prudent financial management. On the other, abandoning the IMF program could lead to a financial catastrophe. Against this backdrop, two medium- to long-term scenarios emerge.

Most likely: The government plays for time

The government will try to avoid meaningful reforms until the 2024 balloting, which in any case is going to take place amid a crisis and popular discontent. As protesters are already marching on the streets for economic and political change, including the resignation of President Akufo-Addo, the campaign may prove particularly volatile.

However, considering the strength of Ghanaian institutions and that the two main parties have managed to maintain a modicum of political and social relevance, a bad political disruption is less likely in the short term. Nevertheless, risks will increase over time, as the root cause of many of the current problems, the electorate’s perception of poor political leadership, is expected to endure. The prospects for the ruling elite’s renewal are poor.

While the country’s financial overextension makes structural reforms more onerous, Ghana has a significant competitive advantage when compared to its neighbors stuck in similar morass. First, there is a potential for the three leading sectors of its economy – agriculture, tourism and mining – to become drivers of sustainable growth. Second, Ghana’s young and educated workforce can make a difference, as the country has consistently invested in extending access to secondary schooling, vocational training and university-level education over recent years. Additionally, the percentage of young Ghanaians who declare plans to return home after studying abroad is encouragingly high.

Unleashing the potential of the economy and repairing Ghana’s democratic foundations, however, would require sound leadership. That, in turn, looks possible only with a generational change in the political elite.

Less likely: Ghana collapses into turmoil

Under this scenario, the multiple tensions resulting from a polarized 2024 elections cause a profound social and political disintegration. To an extent, Ghana’s internal context today is similar to the situation decades ago, when a young Ghana Air Force officer, Jerry Rawlings (1947-2020), seized power in the 1979 military coup, headed a military junta until 1992 and eventually led the country’s transition to democracy, serving two terms as duly elected president until January 2001.

The risk of contagion must also be considered in a region suffering from democratic fatigue and economic dislocation where coups again take place with increasing frequency.

Facts & figures

Ghana Factbox

- Official name: The Republic of Ghana

- Independence: Since March 6, 1957 (from the United Kingdom)

- Capital: Accra

- Political system: Presidential republic

- Area: 238,533 square kilometers, mostly low plains with dissected plateau in the south-central area

- Population: 33,846,114 (2023 est.), approx. 56% under the age of 25.

- Major exports: Diamonds, gold, cocoa, petroleum

- GDP per capita: $2,353 (2022)

- GDP growth rate: 3.2% (Q2 2023)

- GDP 2022 (PPP): $184 billion (2022)

- External debt: $28.14 billion (Q2 2022)

- Inflation rate: 35.2% (October 2023)

- Military: Ghana Armed Forces: Army, Navy, Air Force; personnel 14,000; expenditure 0.4% of GDP

- Transnational issue: Ghana is a transit and destination point for illicit drugs trafficked from Asia and South America to other African countries, Europe and North America. Cannabis is cultivated in large quantities in most rural areas of the country.

Source: The CIA World Factbook, Ghana Statistical services

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.