Post-globalization: The West’s strategy options

After three decades of openness and cooperation, the world is breaking into hostile blocs. For the West, “friend-shoring” may be the best post-globalization strategy.

In a nutshell

- The 30-year-long wave of economic globalization seems to be over

- Paradoxically, global cooperation has strengthened its enemies

- To preserve wealth-creating labor divisions, the West may regroup

We often experience the best of times without realizing it. This is likely how we will feel when we look back at the three extraordinary decades of growth enjoyed by the developed world between the fall of the Iron Curtain and the onset of Covid-19.

We lived through a truly golden age of globalization: the development of international trade, the opening of borders and the breaking down of barriers, the free movement of people and capital, the worldwide division of labor and the involvement of more and more labor in the process of global wealth creation. Brands, firms, products, consumption habits, desires and even hopes, went global. However, the cultural and political underpinnings of all this remained intensely local and unshared.

What went right

The inhabitants of Western Europe and North America may have felt the same way at the turn of the 20th century. But the interdependence of the whole world at that time was not nearly as deep and certainly did not concern such a large part of the world’s population as it did after the cratering of the decrepit communist bloc. And the two devastating world wars of the 20th century, both of which had their epicenter in Europe, brought the Belle Epoque to an end before it could be felt by a genuinely critical mass of the global population.

It was only after China and most countries of the former socialist bloc became involved in the global market and other Asian, African and Latin American nations gradually opened up that genuinely globe-spanning production and organizational sales and logistics chains could emerge.

Facts & figures

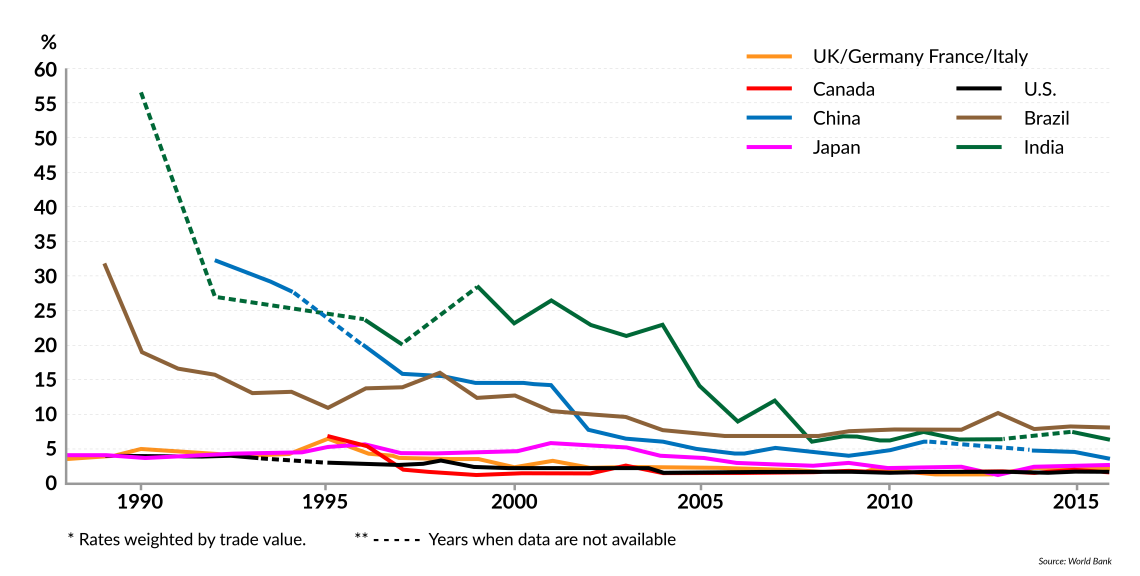

World’s largest economies dropped tariff rates

These chains worked so smoothly that no one even noticed them. They formed gradually, in a decentralized fashion, and the process was rarely even the subject of political struggle and voting. Globalization happened spontaneously, guided soundly and quietly by the market’s invisible hand.

Wealth and interdependence do not necessarily make the world safer and more resilient.

The Europeans benefited from three favorable developments, all happening simultaneously: gigantic new markets growing in China and elsewhere, cheap energy flows from Russia and the robust security umbrella of the United States. Together, these three factors created perfect conditions for wealth creation in the old continent. And for a long while, people were genuinely enthusiastic about the fall of walls and barriers and the brave new world of cooperation and integration. This euphoria made it all the easier for the world of openness to spread further and sink deeper beneath the surface of the European and global economies.

What went wrong

Largely ignored, however, was the possibility that wealth and interdependence do not necessarily make the world safer and more resilient. These factors can actually make it more fragile and vulnerable. The bet on China and Russia “Westernizing” in the free-market environment did not pan out. The global hegemon, the U.S., certainly tried to make things work, despite its various missteps. Not that the results of its endeavors have not been impressive in the past. Modern-day Japan, South Korea, and even the interconnected Europe are successful results of postwar U.S. endeavors to create a freer, more open and less dangerous world. American political scientist and author Francis Fukuyama even believed that the U.S. had scored a final historical triumph by winning the Cold War.

Read more on U.S.-China trade conflict

The U.S. and China: The trade war and the broader confrontation

However, something different happened in “the country of new markets,” China, and “the country of cheap resources,” Russia. Citizens of the two preeminent former communist powers may have wanted a Western standard of living. However, their rulers did not want Western political, legal and constitutional norms.

Instead of boring democracies, each break from the economic morass of the past gradually turned these two countries into classic, increasingly dangerous autocracies. They had their interests, visions of the world and appetites for domination.

Two comeback attempts

The order of globalization and openness has created alternative superpowers – challengers and deniers of that same world order. In China’s case, it has directly produced a strategic rival to America, one proud of its thousands of years of history and making no secret of its intention to displace the U.S. as the world’s dominant power.

Former U.S. President Barack Obama (2009-2017), while a believer in globalization ( it’s „here” and „done,” he claimed), played a curiously counterproductive role in this titanic struggle. He thought he could blunt China’s aspirations by offering it a share of the hegemony: hence projects like the G20, the talk of inclusive world governance, the deal with Iran and many others. Dyed-in-the-wool autocrats will, of course, always interpret such gestures as weakness. In retrospect, it was unsurprising that the American electorate reacted to President Obama’s pipe dreams by moving to the opposite extreme – the presidency of Donald Trump (2017-2021). That president had no qualms about defending his country’s place at the top of the heap, even if he would have to use its military power. However, the legacy of the much-denounced Mr. Trump in American politics is arguably more substantial and widely shared among the leading players than Mr. Obama’s.

China represents a specific mix of capitalism, socialism, totalitarianism and nationalism. Since 2012, it has been tending more toward the latter two ‘isms.’

The developments in China may seem particularly paradoxical to Western observers because no other country has lifted such vast numbers of people out of poverty in such a short time as the Middle Kingdom. And it has done so solely by deploying the West’s most potent yet intangible weapon: the free market. The Communist party-run China began to prosper by introducing the freedom to own property and do business and opening its economy to global investment, innovation and competition. (The economist Ronald Coase brilliantly described that process in “How China Became Capitalist.”) One must add that China owes its rise also to unfair practices toward the rest of the world and noncompliance with World Trade Organization (WTO) principles. That behavior was naively tolerated because of the size of China’s markets and the Westerners’ faith in its “Westernization.”

Yet it had long been apparent that China represents a specific mix of capitalism, socialism, totalitarianism and nationalism. Since 2012, it has been tending more toward the latter two “isms.” It definitively ceased to be seen as a future new member of the Western world when its current president, Xi Jinping, was appointed paramount leader without term limits. There is always a danger to the liberal international order when a systemically important country falls under the rule of an individual who can do whatever they please.

The situation denies the principle of checks and balances on which the rules of the free world are based. Add to that China’s policy of “national pride” – in fact, crude nationalism – and its ongoing policy of “Hanization” (the forcible relocation of the majority Han population to regions inhabited by minorities), and we have a disaster that has long been in the making. The crushing of Hong Kong’s independence and the immense threat to Taiwan tell the rest of the story. As, indeed, does the tragedy of Ukraine at the hands of Russia and its present tsar.

Authoritarians’ weak spot

Remarkably, both countries lack what they most need and want. Unlike America and parts of Europe, China and Russia do not inspire people. With a few exceptions (like TikTok), the developed world neither imitates nor worships contemporary Chinese or Russian culture, celebrities, social and other media, music, cinema, universities or politics, and rarely adopts their products, brands, and forms of entertainment and leisure.

The East still copies the Western standard, not vice versa. China makes Western products, and Russia supplies the West with energy to produce and consume them, not the other way around. And their citizens, especially the wealthy and the educated, vote with their feet by emigrating to the West. Very few move in the opposite direction.

As American economist and former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers cynically surmised when asked whether another currency might soon threaten the U.S. dollar’s global dominance: how could that happen when Europe is a museum, Japan is a nursing home, and China is a jail? In this sense, Russia is economically far too weak to even be considered a serious contender by that observer. Yet it is the West, with its tendency for self-flagellation and culture wars, that has become insecure in its role and ceased to appreciate the values that made its historic dominance possible.

The different political underpinnings of globalization in different countries have caused tectonic movements on a massive scale.

By taking that route, the West inadvertently stoked sympathy among a minority of its population for totalitarian Sino-Russian alternatives. It also intensified the hatred toward it in many other countries. It is not for nothing that global surveys show that countries in which people view Russia positively nearly always have a favorable view of China, and vice versa.

Systemic shocks

In any case, the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s aggression toward Ukraine have at least shown democratic Europe the limits of globalization. In a short time, Western populations have experienced a powerful shock: they discovered how interconnected the world is and how much dislocation occurs in everyday life when restrictions and conflicts upset the global division of labor – production, logistics and “just-in-time” systems. People have also realized how dependent they are on others and on the decisions of regimes and rulers who trade in the same markets but do not belong to the same cultural circle. Suddenly, the different political underpinnings of globalization in different countries have caused tectonic movements on a massive scale.

This rude awakening from the carefree global openness leads many countries to withdraw inwardly. This process is compounded by the fact that Russia’s super-cheap energy has become largely unavailable, and that assuring the continued security protection of the U.S. may require either a substantial sacrifice of China as a trading partner or considerable investments in defense, or a combination of the two. It is as if all three winds have stopped blowing at the same time. This situation requires Europe to make some very tough decisions.

The forces of deglobalization will not be easy to contain. With a tsunami-like strength and speed, these forces sweep aside everything in their path. Europe – a common market continent riddled with various historical borders – could still limit the rollback of all the good things that the international division of labor has brought. However, the time is difficult for such an endeavor when the populations of individual nation-states often demand simplistic, ineffective and expensive solutions to global problems at the national level. That is what the current energy crisis tells us.

Scenarios

The Western world is at a crossroads. It could go in the direction of erecting borders and barriers, as U.S. President Joe Biden’s protectionist policies indicate, or safeguarding the benefits of trade with China, as some European countries have advocated – or opt for a closer transatlantic cooperation between friends, not between friends and enemies.

Former Federal Reserve Chair and current U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen argues that after the era of outsourcing and offshoring, only “friend-shoring” offers a viable alternative to the Western world. Not the end of the division of labor, but more significant cooperation between the geopolitically similar and culturally close.

The West, particularly Europe, will need to make a historic decision about its reaction to the deglobalization and economic fragmentation process.

Scenario 1: Independence from autocrats

The first scenario assumes that intensified global threats will bring the world’s democratic and free-market economies close together, causing them to cooperate more closely through broader trade, political and security agreements, with fair sharing of the costs of common defense and the benefits of cooperation. “Friend-shoring” will become a standard part of Western business and government thinking, preventing a sharp decline in the wealth-generating division of labor in the Western world. At the same time, the West will focus on creating strategic energy and production independence from the world of autocracies. The probability of this scenario is about 40 percent.

Scenario 2: Weakness behind trade barriers

This scenario assumes that the shortsightedness of the political process in Western countries, the rise of populism and general discontent among voters and the demand for simple and quick solutions will make it politically easier to create new barriers and increase protectionism even among Western countries. As a result, they will end up economically and politically weaker. The probability of this scenario is 50 percent.

Scenario 3: Democracy’s twilight

The catastrophic scenario is that some Western countries, under pressure from deglobalization, rising prices, aging populations and falling living standards become semi-democratic or autocratic. That will not solve their problems, but it will exacerbate global misery. The probability of this scenario is 10 percent.