The race to tax fossil fuel profits

Efforts to impose windfall taxes on booming energy companies are often misplaced and expose flaws in national fiscal systems.

In a nutshell

- Oil and gas firms have seen banner profits amid the war in Ukraine

- The political backlash against fossil fuel companies is mounting

- Many windfall taxes have not been designed with best policy practices

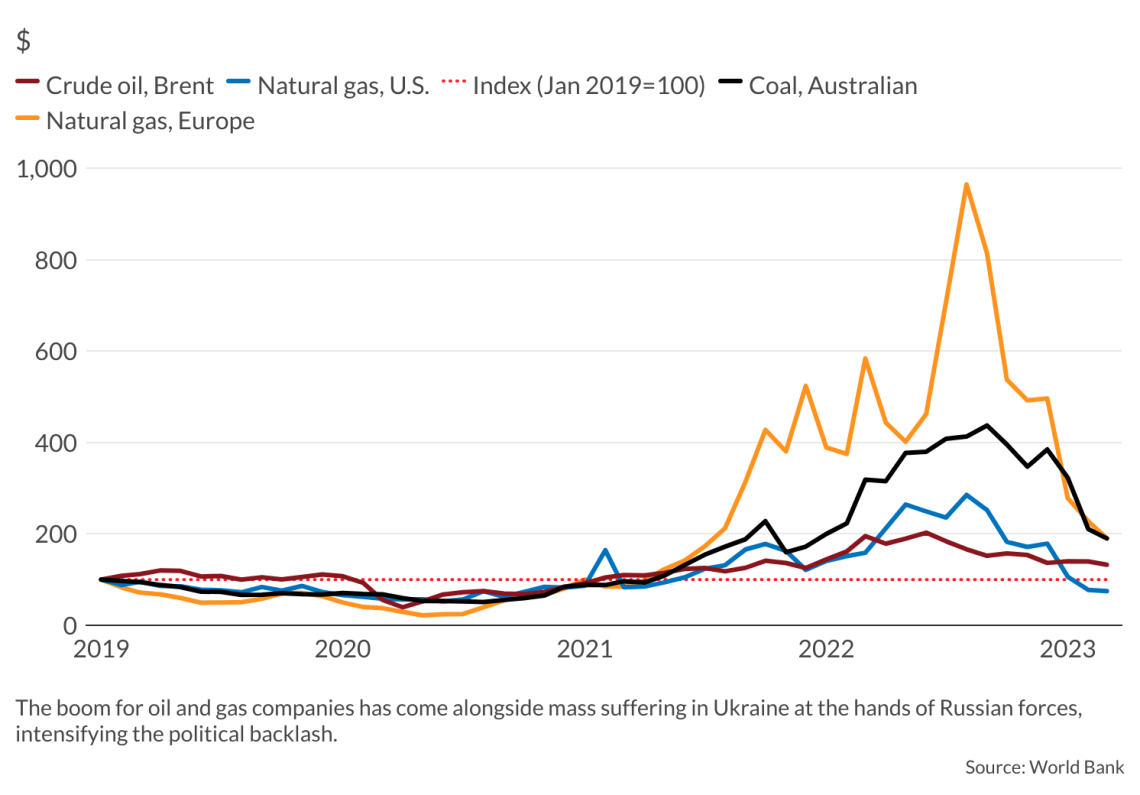

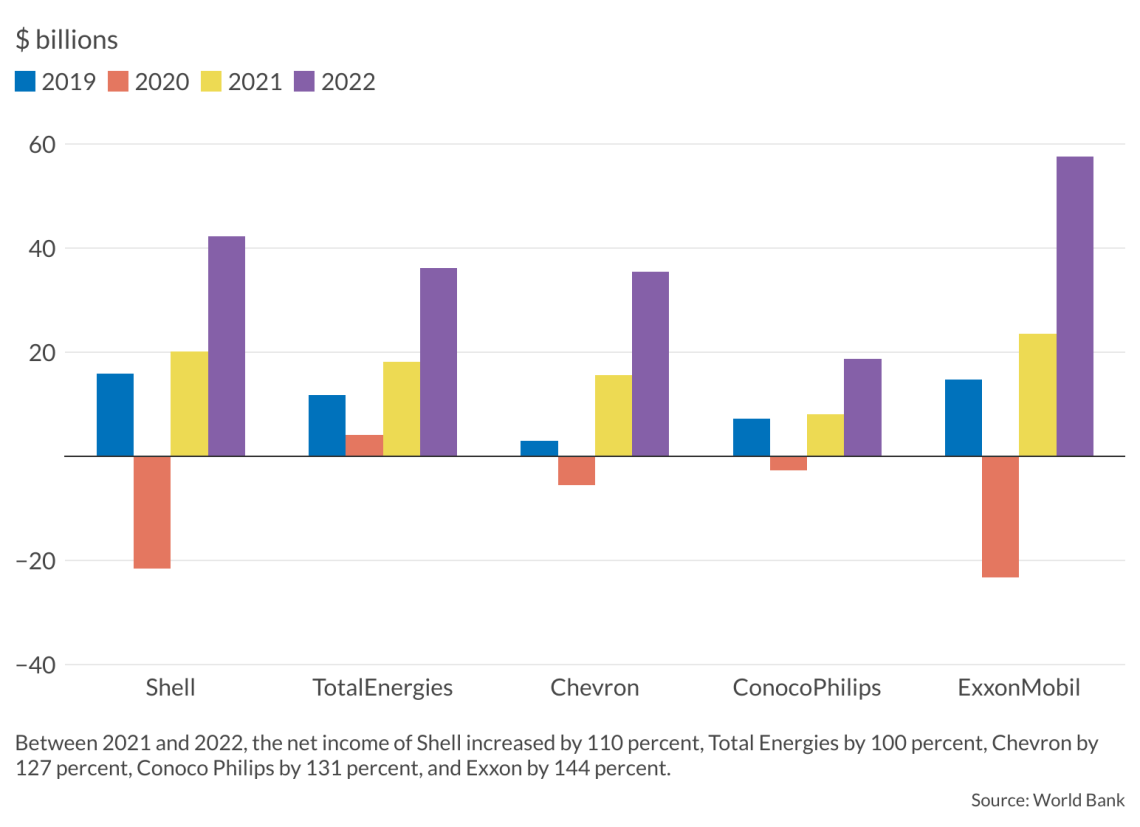

The rapid increase in oil and gas prices in 2022 yielded a notable rise in profitability for energy companies worldwide. “Our full-year 2022 results clearly benefited from a buoyant market,” said Darren Woods, chairman and CEO of ExxonMobil, the world’s largest privately owned oil company. But outside the industry, these profits stirred controversy. This came not only from environmentalists seeking to marginalize the industry, but also because of the significant financial burden that high energy prices have placed on consumers and businesses, leading to a politically precarious situation.

Many governments have come under pressure to rectify what is seen as a significant market failure and an unfair situation, particularly as the energy price spike has been fueled by war. In a tweet from August 2022, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres criticized the industry’s profitability, stating, “It is immoral for oil and gas companies to be making record profits from the current energy crisis on the backs of the poorest, at a massive cost to the climate.” Even in the United States, the world’s largest oil producer and the proclaimed champion of the free market, oil profits have provoked backlash at the highest levels of authority. President Joe Biden has called these companies’ gains “outrageous,” adding, “their profits are a windfall of war – the windfall from the brutal conflict that’s ravaging Ukraine and hurting tens of millions of people around the globe.”

Facts & figures

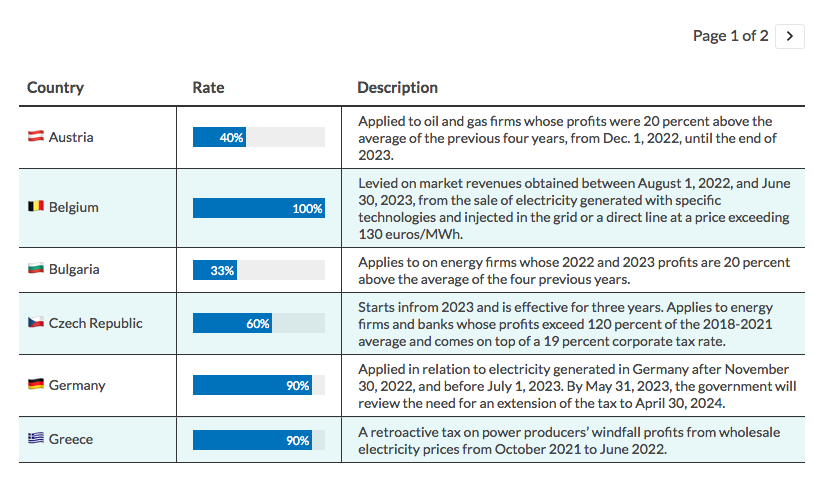

Such rhetoric has not yet resulted in windfall taxes on the U.S. oil industry. Despite the softer public tone taken by its leaders, it is Europe, which has felt the greatest brunt of high energy prices, where new windfall taxes have been most prominent. Taxes have been introduced or increased in at least 12 European countries, while the European Union has unveiled a “solidarity contribution” program for fossil fuel industries – “in a spirit of fairness,” as Economy Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni put it.

These developments are not surprising. From its inception, the relationship between the oil and gas industry and host governments has been largely shaped by oil prices, albeit asymmetrically. Higher prices have consistently attracted higher taxes on the industry, long before climate considerations came into play and regardless of what caused the price fluctuations. In contrast, while lower prices can result in a reduction of the fiscal burden, governments typically react slower to them, if they react at all.

Petroleum taxation is the primary system for distributing hydrocarbon wealth between host governments and investors. However, there is no universally agreed-upon measure to quantify what constitutes normal or abnormal profits (let alone “outrageous” or “immoral”). The definition of what comprises a fair share is also continuously evolving; a 30 percent tax might be considered fair when oil prices are $50 per barrel, but unfair when prices increase.

However, if a tax system is properly designed from the outset, it should automatically adjust to changes in market conditions with minimal or even no government intervention. The tax rush of 2022, while understandable, has underscored flaws in the design of many existing fiscal systems worldwide. For this, national governments are to blame.

What is a windfall profit?

A “windfall” is defined as “an amount of money that somebody/something wins or receives unexpectedly.” It is also described as a sudden, unearned advantage or benefit, i.e., a financial gain achieved without any particular effort. “The oil and gas sector is making extraordinary profits, not as the result of recent changes to risk taking or innovation or efficiency, but as the result of surging global commodity prices, driven in part by Russia’s war,” stated then-British Chancellor Rishi Sunak in 2022, before he took the prime minister’s office. In theory, a government can then tax this additional profitability without affecting the industry’s behavior.

Facts & figures

In practice, however, several complications arise, beginning with identifying the threshold at which profits are deemed windfalls. In the EU, the “solidarity contribution” applies to profits that exceed a 20 percent increase in the average yearly taxable profits since 2018. It is unclear, however, why this threshold has been set, and it is not universally adopted. Further, while most EU member states follow the proposed average earnings method to define the tax base for the solidarity contribution within the sector, one study found variations in the implemented tax bases. The applicable tax rate ranged from the minimum rate of 33 percent to 75 percent, along with variations in the application period of the solidarity contribution.

Progressive taxes

Typically, sectors outside of oil are primarily subject to a corporate income tax (CIT). In the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the average CIT rate has fallen to 23 percent, compared to 30 percent in 2002. For the oil industry, the CIT is just one of several fiscal instruments that are applied; collectively, they constitute the petroleum fiscal regime. The total proportion of revenues accruing to the government from oil and gas activities is known as the government take, which typically ranges between 65 and 85 percent and can in some instances exceed 90 percent. Introducing new taxes on the industry should consider the existing system and how the new tax will interact with other instruments, including the treatment of specific deductions.

Moreover, because the rules attached to each instrument vary significantly between countries, comparing headline rates can be misleading. For instance, in Norway, the total government take is around 78 percent, while in the U.S. (specifically in the Gulf of Mexico) it is around 45 percent. While the Norwegian fiscal regime appears more burdensome at first glance, it is in fact more lenient than its American counterpart since it is entirely profit-based (in addition to the general CIT at 22 percent, a special petroleum tax of 71.8 percent is levied on profits).

Facts & figures

In contrast, in the U.S., the industry makes a substantial payment in the form of a signature bonus before any operations begin. This comes in addition to a royalty, which is levied on revenues (not profits), as well as the profit-based CIT. As a result, the Norwegian system responds better to changes in the industry’s profitability than the U.S. system and is therefore progressive – an important feature of an ideal fiscal regime. In contrast, due to its heavy reliance on nonprofit-based instruments, the American fiscal system is regressive: the government share decreases when profitability increases (and vice versa).

Tax stability and neutrality

Equally important, the Norwegian system is among the most stable fiscal regimes in the world, another key principle. Fiscal stability offers a level of predictability and reliability that enables governments to estimate how much revenue will be collected and when; for investors, this secures the basis on which prior investment decisions were made.

In this respect, another problem arises with the additional taxes recently introduced, particularly in Europe: they are temporary or one-off, which is not in line with commonly recommended tax policy. The International Monetary Fund advises against imposing such taxes, which can increase risks for investors seeking a stable and predictable tax regime, and might be more distortionary (especially if poorly designed or timed), while not providing revenue benefits above those of a permanent tax. Instead, the organization suggests introducing a permanent tax on windfall profits from fossil fuel extraction only if an adequate fiscal instrument is not already in place.

Another important feature of an ideal tax is simplicity: the tax should be easy to understand, implement and administer, and levied on a well-defined tax base. Such a tax enhances transparency and reduces the administrative burden for both administrations and tax-paying businesses. The rush to introduce windfall taxes has compromised this feature of the fiscal regime in several countries.

The United Kingdom’s petroleum fiscal system is infamous for the numerous changes introduced over the years, a habit that continues to this day. In May 2022, the government introduced an energy levy first at 25 percent, which was subsequently increased to 35 percent a few months later. This adjustment brought the total government share to 75 percent, the highest in decades and a far cry from the total 30 percent the industry once enjoyed in the 1990s.

Furthermore, when the levy was first announced, the government offered an investment allowance whereby “for every pound a company invests, it will get back 90 percent in tax relief,” as Rishi Sunak, then serving as chancellor, put it. “We should not be ideological about this; we should be pragmatic. It is possible to both tax extraordinary profits fairly and incentivize investment,” he argued, in support of the government’s ambition “to see the oil and gas sector reinvest its profits to support the economy, jobs, and the UK’s energy security.”

However, this allowance was soon reduced to 29 percent as of January 2023, and the duration of the levy’s application was extended from 2025 to 2028, creating an uncertain investment path in the country’s oil and gas sector, which is dominated by smaller players.

There is no universally agreed-upon measure to quantify what constitutes normal or abnormal profits, let alone “outrageous” or “immoral.”

As one study concluded, the effects of the updated Energy Profits Levy on new investment in the UK Continental Shelf are complex, particularly as it discriminates between different investors, exposing them to varying fiscal burdens depending on when they undertook or plan to undertake their investment. For instance, if an investor has incurred project investment costs prior to May 2022 and has substantial income between 2022 and 2025, the revised levy significantly negatively impacts their posttax returns, the study found. This outcome does not align with another crucial principle of good taxation, which is neutrality: a neutral tax does not distort investment decisions.

It’s difficult to argue against a higher government take from the oil and gas industry, which holds the potential for significant economic rent – the surplus return. However, a government with a well-designed fiscal regime in place doesn’t need to chase the volatile oil prices, an inherently challenging task.

Any effective tax policy is rooted in well-established principles of progressivity, stability, simplicity and neutrality. Failure to adhere to these fundamentals will jeopardize the policy’s durability and its intended outcome. As the finance minister to French King Louis XIV, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, once said, “the art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to obtain the largest amount of feathers with the least possible amount of hissing.”