Turkmenistan comes into focus

Turkmenistan has recently begun to matter in international politics. The reason is a sharp drop in energy prices, which has turned the gas-rich country into an economic basket case, and the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan.

In a nutshell

- Both Russia and China see Turkmenistan’s internal crisis as a threat to their interests

- Low energy prices and security issues have tightened China’s grip on Turkmen gas exports

- Moscow is offering help, but only Beijing has the resources to bail out Ashgabat

Long neglected by all but devoted Central Asia specialists, Turkmenistan has recently begun to matter in international politics. The reason is a sharp drop in energy prices and the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan. Both developments have put Turkmenistan squarely on the radar screens of Russian and Chinese policymakers.

Each country believes their vital interests in the increasingly important Central Asia region are coming under threat. A shared concern is that Turkmenistan, with the world’s fourth-largest natural gas reserves and a 750-kilometer border with Afghanistan, may simply collapse as its income from energy exports shrivels. While such fears may be overblown, the concern on both sides is genuine enough.

Systemic failure

Turkmenistan’s transformation into an economic basket case arrived with little warning. The country had long vegetated in self-imposed isolation. Coasting on income from foreign sales of cotton and gas, President Saparmurat Niyazov (1990-2006) developed a harsh and eccentric form of authoritarianism that attracted little outside attention.

Based on a social contract that entailed free gas, water, electricity and health services, the system seemed to be working just fine until about a decade ago. The subsequent steep fall in world energy prices shined a harsh light on the underlying fragility of this financial arrangement.

While it would be an exaggeration to compare Turkmenistan’s plight with the ongoing state collapse in Venezuela, the situation is extremely serious. Unemployment is believed to be around 50 percent. The black-market rate against the dollar for Turkmenistan’s currency, the manat, increased from 6 in 2016 to 30 in 2018. Gas, water and electricity are no longer free for ordinary citizens, while the price of medicines has rocketed. There are shortages of staple goods like flour.

Energy shift

These developments are naturally worrying to China, which has extensive investments in Turkmenistan and whose energy security depends on the continued expansion of Turkmen gas exports. From the Russian side, the main concern is keeping the instability in Afghanistan from spreading to Central Asia and over its own border.

A key feature is that control over the region’s critical energy infrastructure has decisively shifted from Russia to China in recent years. Russian overtures to resume long-suspended purchases of gas from Turkmenistan, evidenced in surprise visits to Ashgabat by Gazprom CEO Aleksei Miller in October and November 2018, only drive home just how complete the Chinese hegemony has become.

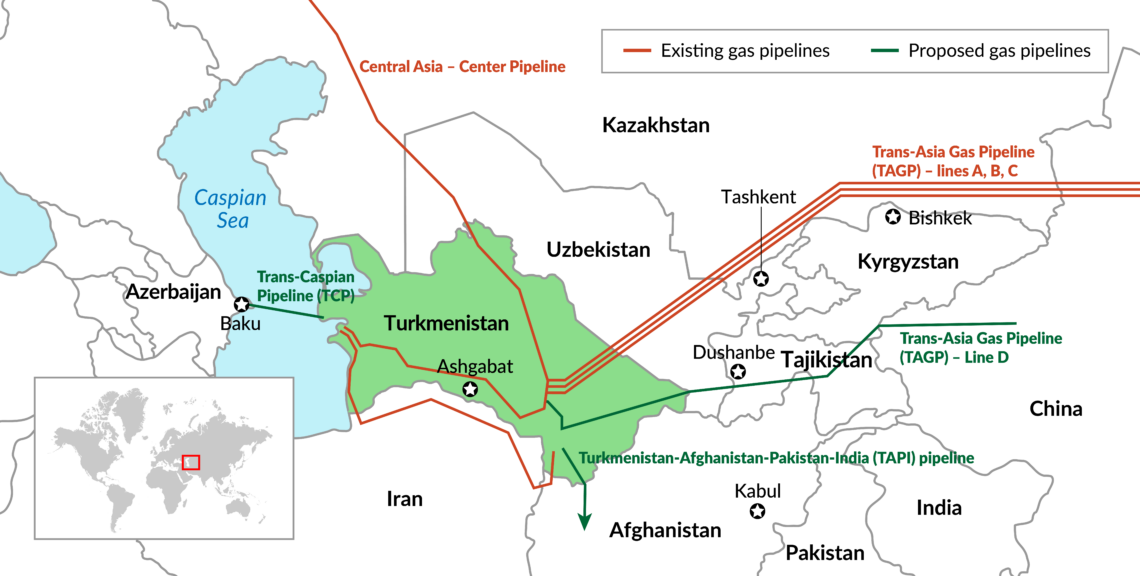

Until 2009, Russia was convinced that Central Asia’s gas would flow north through its Central Asia-Center network.

Until 2009, Russia was convinced that Central Asia’s gas would continue to flow north through its Central Asia-Center network. A deal struck in 2003 envisioned exports rising to 80 billion cubic meters (bcm) over 25 years, starting in 2009. In 2008, the picture still looked promising, with Turkmenistan making deliveries of 40 bcm.

Russia’s problem was that it became too sure of its market power in Europe, which led it to agree to demands from Central Asian suppliers for hefty price increases. After paying just over $30 per thousand cubic meters (tcm) in 1998, Gazprom was ready only a decade later to accept “European” prices of $400 or more, believing the increase could be passed on to customers in Europe.

During the first quarter of 2009, the sharp drop in energy prices cost Gazprom over $1 billion on gas purchased from Central Asia and resold at a loss in Europe. While Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan agreed to lower their prices, Turkmenistan refused. The saving grace arrived in early April, when a mysterious explosion close to the Turkmen-Uzbek border shut down the CAC-4 pipeline, halting nearly all exports of Turkmen gas.

Gas deals

Sensing a window of opportunity, China rushed to make good on a 2006 deal to jointly develop Turkmen gas fields for export to China. The first section of the Central Asia-China pipeline, with a capacity of 40 bcm, opened in December 2009. This decisive move improved energy security in China’s western regions, but above all it allowed Beijing to play hardball with Moscow over energy resources in Siberia and the Far East.

Russia and China have since concluded several major energy deals, ranging from the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean oil pipeline and a 30-year supply deal with Rosneft, to the Power of Siberia gas pipeline to handle export shipments from the Russian Far East. While Russia has touted these deals as great achievements, it is unclear what terms the Chinese have secured. And the bargaining is far from over.

Russia badly wants China to buy gas from Altai, where fields are ready to be pumped. But Beijing is more interested in tapping into the massive reserves that remain to be exploited in Turkmenistan.

Only customer

The China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) has production sharing agreements in place for the Galkynysh and Bagtyyarlyk fields. With these sources added, Turkmenistan’s total gas exports could rise to 65 bcm, from 35-40 bcm at present. But increased output will require pipeline expansion, because existing capacity is close to full. This is where the outlook for the Turkmen economy becomes so critical.

The cessation of Turkmen gas exports to and via Russia was a major geopolitical shift, placing Turkmenistan in a position of complete dependence on Beijing. In 2017, China took 94 percent of Turkmen gas exports, representing 90 percent of the total value of the country’s exports. It had also bypassed Russia as Turkmenistan’s largest creditor.

At the start of 2016, China was reportedly paying no more than $185/tcm, far below the price levels anticipated in 2008. And in February 2017, a CNPC delegation arrived to demand even lower prices. Although the outcome of the talks is not known, it is believed that the agreed formula linked the gas price to that of oil. What is clear is that the global decline in energy prices means that an even larger share of Turkmenistan’s gas revenue must go to service loans received for pipeline construction. This fiscal squeeze exacerbates the country’s economic crisis.

Turkmen bargaining power is constrained by the fact that China is its only customer. Having already lost its exports to Russia, in early 2017 Ashgabat suspended sales of gas to Iran, citing an outstanding debt of $1.8 billion. Little has come of long-discussed plans to build alternative outlets.

Export options

One such scheme is the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline. Pumping gas to energy-starved Pakistan and India would in theory make a lot of sense, but in practice both security and finance must be factored in. The Taliban have said that they can guarantee security in Afghanistan, but for a major long-term investment, that assurance has dubious value. It is also debatable whether anyone able and willing to finance the $10 billion investment can be found. In consequence, TAPI is not likely to happen soon.

A more tantalizing proposition is the Trans-Caspian Pipeline (TCP), which has been on the table for a couple of decades. The TCP would pump Turkmen gas across the Caspian, onward to Turkey and into Europe, feeding the Southern Gas Corridor. The project’s business logic is sound, since it would provide a direct outlet for Turkmenistan’s huge gas reserves.

China is well-positioned to import even more gas from Turkmenistan, but for the latter’s deepening economic crisis.

Yet while Turkey has pressed hard to advance the TCP, both Russia and Azerbaijan have objected – and the Europeans have vacillated. The signing of the Caspian Convention in 2018 has likely put an end to it, since all five littoral states have been given veto power over pipeline construction. Both Russia and probably Iran would probably block Turkmen ambitions to build the TCP.

The foregoing suggests that China is in an excellent position to keep increasing its gas deliveries from Turkmenistan. But the deepening economic crisis in the latter country could yet throw a spanner in the works.

Russia returns

In the Russian view, Turkmenistan is above all a security problem. Until the United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001, the Turkmen-Afghan border was a tranquil place. Even as the U.S. campaign was pressed home, Ashgabat maintained good relations with the Taliban, much to the anger of Russia and its Central Asian neighbors.

But as the situation in northern Afghanistan began to deteriorate, from the start of 2014, trouble also began along the border with Turkmenistan. In 2016, there were reports of clashes with militants leading to the death of three border guards in February and of three soldiers in May. Further clashes have been reported but routinely denied by the government. Yet, as tensions have mounted, there has been an increase in defense spending, snap military drills and a drive to register reservists.

It is significant that Russian sources now refer to the border between Turkmenistan and Afghanistan as a “common CIS-border.” During a visit to Ashgabat in February, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov repeated a prior offer to help strengthen border security. A visit in June by Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu drove the message home. Despite its proclaimed neutrality, Turkmenistan is in no position to decline such help.

These overtures from Moscow provide the key context for Russia’s sudden expressions of interest in resuming gas purchases from Turkmenistan. Why on earth would Russia even consider this possibility, when it is already anxious to sell more of its own gas to China?

One explanation is that Turkmenistan is desperate to sell more gas. Russia has a pipeline in place and can start importing immediately. This could be Moscow’s way of thanking Ashgabat for signing the Caspian Convention, puttingan end to its prior covert negotiations with the U.S.

Russian gas purchases may also help dissuade Ashgabat from persisting with the TCP. That would protect Gazprom’s vital European market, where gas sales are far more profitable than in Asia. From Moscow’s point of view, it is far more advantageous that Turkmen gas flows east to China rather than west to Turkey and Europe.

Even if gas exports are resumed, Russia is unlikely to take more than 4-5 bcm, and that at a low price. This reflects Russia’s severe financial constraints, which put hard limits on what it can afford to spend on securing its interests in Central Asia. That leaves the initiative firmly in Chinese hands.

Limited options

Scenarios for future developments will hinge on just how badly the economic situation in Turkmenistan deteriorates.

Shortages of basic food items, including bread, sugar and cooking oil, are said to have worsened in recent months. There have even been reports of food riots. While the situation is bad in Ashgabat, it is even worse in the provinces. In early December 2018, the government informed regional administrations that they will have to fend for themselves, and in February 2019 roadblocks were set up to keep motorists from making unauthorized trips to the capital. The authorities have also begun clamping down on attempts by citizens to leave the country to seek jobs abroad.

Russia’s plan to shore up security along the border is likely to proceed. Following its template of an enhanced military presence in Tajikistan, the acting head of the Central Military District, Yevgeny Ustinov, announced in December 2018 that there would also be renewed military training of Turkmen and Uzbek forces.

The dilemma for Beijing is whether it will need to intervene with subsidies to stabilize the Turkmen economy.

The question of gas imports and economic cooperation is a different matter. On the eve of Aleksei Miller’s visit in October, President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov spoke to President Putin about the need to diversify economic relations and promote trade and investment. During 2018, Russia pursued precisely that policy in Uzbekistan, with a fair degree of success. Yet, although Gazprom has mentioned the possibilities of moving into energy processing and chemicals, the likelihood that the Uzbek success will be repeated in Turkmenistan is small.

One cautionary tale is the fate of Russian telecom operator MTS, which was forced to suspend its Turkmen operations in September 2017. Claiming to have been pushed out by a new state-run operator, the company filed a $750 million complaint with a World Bank arbitration center. In January 2019, MTS packed up and left. The implication is that Russia may be powerless to do much to alleviate Turkmenistan’s economic crisis.

China’s dilemma

Given that China’s demand for gas is expected to grow at an annual rate of 8.7 percent until 2022, its concerns about Turkmen gas exports keeping pace are plenty serious.

Even though liquefied natural gas (LNG) is twice as costly as piped gas, Beijing has been forced to expand LNG imports and is forecast to overtake Japan as the world’s No. 1 importer this year. Another reason Beijing prefers overland gas deliveries by pipeline is that it reduces the dependence on tanker shipments passing through the vulnerable Malacca Straits.

For the moment, China’s infrastructure plans remain on track. Following some wrangling with transit states, work on the fourth and final part of the China–Central Asia pipeline system, known as Line D, was recently resumed. Once the project is completed, Turkmenistan’s annual gas exports can be brought up to 65 bcm.

The dilemma for Beijing is whether it will need to intervene with subsidies to stabilize the Turkmen economy, propping up the currency and rescuing the banks. Perhaps it will even need to put together a stability package to support economic reforms. This would be a total break with practice to date.

China could always use defaults to take control of local energy assets, in line with the policy of providing loans for resources that it has deployed in Venezuela and Angola. But if Turkmenistan is seriously destabilized, and China has assumed responsibility for assistance, it will end up being blamed. Chances are that things will work out, but Beijing could still be in for some nasty surprises.