In fractured Libya, it’s about oil

As the civil war in Libya sputters on, its principal source of revenue remains oil fields. The feuding Tripoli and Tobruk governments have allowed the National Oil Corporation to keep managing operations. A power struggle is disrupting the flow of oil and cash as General Haftar squares off against the Government of National Accord.

In a nutshell

- Libya’s warring factions have largely kept their hands off the oil and gas industry

- With UN-brokered elections nearing, feuding over oil revenue has started

- The most active foreign powers, France and Italy, are at odds over the vote’s timing

Oil is Libya’s economic lifeblood, accounting for 82 percent of the country’s exports and 50 percent of its gross domestic product. It provides most of the budget revenue. Before the overthrow of longtime revolutionary leader Moammar Qaddafi in 2011, the country produced 1.6 million barrels per day. Its proven reserves are estimated at 46 billion barrels.

Libya’s oil and gas output has lagged for many years, first because of international sanctions on the Qaddafi regime and later due to disruptive effects of civil war. Now the country needs to explore for new oil fields to replace those nearing maturity. The low production cost and low sulfur content of Libyan oil justify its “sweet crude” appellation, with the extra bonus of proximity to European markets that account for 85 percent of Libya’s exports and 11 percent of its imports.

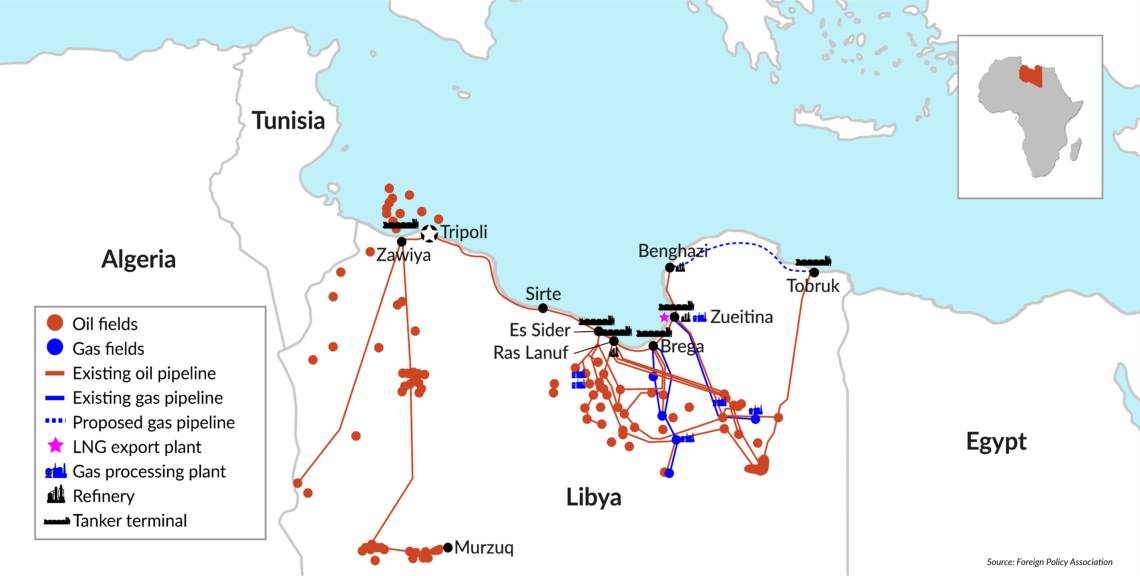

Oil production and export terminals are mainly concentrated in the northeastern and north central parts of the country, including the Sirte basin running between Qaddafi’s hometown of Sirte to Ajdabiya. The country’s two main oil ports and terminals – Ras Lanuf and Es Sider – can be found along this stretch of coast, along with their refineries and storage facilities. Oil and gas from the wells in the desert hinterland reach these terminals through an extensive pipeline network.

There are two more terminals in the western part of the country, Zawiya and Mellitah, which get their crude mainly from the Murzuq and Ghadames basins. The Sirte basin, often called “the oil crescent,” is the hub of Libya’s economy. Whoever controls oil exports from that area has a significant strategic edge in the fight to control the rest of Libya.

These huge resources are administered by the National Oil Corporation (NOC) and the Central Bank of Libya (CBL). Both institutions somehow managed to retain their independence throughout the civil war, discharging their duties uncompromisingly and keeping Libya financially solvent. Whether they will keep on doing so depends on the current political maneuvering over the fate of national elections, which are supposed to be held in December.

Political standoff

Libya’s seemingly inextricable predicament after Qaddafi stems from the country’s second parliamentary elections in 2014. They were won by secular parties, which displaced Islamic movements led by the Muslim Brotherhood that had prevailed in the 2012 elections. The Islamists refused to accept defeat and launched violent attacks on the newly elected House of Representatives (HoR), which was forced to flee the capital, Tripoli, and relocate to the city of Tobruk.

General Khalifa Haftar, returning from exile in the United States, gathered together and reorganized the remnants of the Libyan National Army (LNA) and pledged allegiance to the HoR, which was recognized by the international community. They were opposed by the old and now illegal parliament elected in 2012 – the General National Congress (GNC).

Over the past two years, damaged terminals have been restored to service and oil output has risen.

Chaos ensued as scores of Islamic militias and criminal gangs rampaged through the country. In 2014, General Haftar launched a failed offensive to liquidate the Muslim Brotherhood and take Tripoli. He went on to fight Islamic Jihadist militias in Benghazi and Derna that posed a threat to his hold on eastern Libya. Pockets of Islamic resistance survive in these cities, which still experience sporadic terror attacks.

During the worst months of the civil war in 2014-2015, oil exports almost ceased. Not until late 2016 did the LNA reconquer the Sirte crescent, allowing law and order, and handed back to the NOC the vital oil installations. Over the past two years, damaged terminals have been restored to service and oil output has risen to 700,000 barrels a day, quite a feat under the circumstances.

The present political dialogue between Tripoli and Tobruk is based on an agreement reached in December 2015 in Skhirat, Morocco, under the auspices of the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) and its head, Martin Kobler. Representatives of both sides signed a “Libyan Political Agreement” which was supposed to lead to cooperation and the formation of a Government of National Accord (GNA) tasked with preparing general elections. But General Haftar refused to endorse it, probably because he was not promised command of the future national army.

After protracted negotiations conducted with UNSMIL’s help, a Presidential Committee headed by Fayez al-Sarraj, a former minister of housing and utilities, was formed. This committee eventually formed a Government of National Accord chaired by Mr. al-Sarraj himself. This interim government is assisted by a High State Council, mirroring the Tobruk HoR. Policy-making and senior appointments have to be agreed by both houses.

Even though it was now the only government recognized by the international community, the GNA found itself unable to take effective control over the country. It had to deal with the authorities in Tobruk and General Haftar’s LNA, which draw their legitimacy from the House of Representatives, as well as with Islamist militias in the country’s west.

Libya’s two main factions have reached agreement on elections, but not on the distribution of oil revenues.

French President Emmanuel Macron took the initiative to bring together Mr. al-Sarraj and General Haftar. Their meeting in Paris in July 2017 paved the way for a larger conference in May 2018, also in Paris, with the participation of Fayez al-Sarraj, Khalifa Haftar and the heads of both parliaments. The agreement that ensued fixed parliamentary and presidential elections for December 10, 2018. A new constitution and electoral law to be confirmed by a referendum were to be drafted by September 16. The draft constitution has already been approved by the High State Council in Tripoli and will be submitted to a national referendum as soon as the Tobruk HoR clears the measure – which so far it has not done.

Bargaining chip

Though Libya’s two main factions have reached a broad agreement on elections, they have yet to come to terms on the distribution of oil revenues and the division of power after the elections.

The oil issue came to the fore again in June, when General Haftar retook the Sirte terminals, driving away Islamic militias for the third and hopefully last time. On June 26, he proclaimed that the NOC, headquartered in Tripoli, would no longer control oil production and exports. Instead, that task would be assumed by a breakaway NOC branch located in Beida, in eastern Libya.

This move did not win approval from the international community, which continued to recognize the NOC as the sole operator of the national oil industry. It exposed the Beida branch of the NOC to sanctions based on several UN Security Council resolutions. Export sales were virtually stopped, since past attempts at smuggling oil out of the country had been blocked by American warships.

The oil feud marked a new twist in the battle with official institutions situated in Tripoli. Following General Haftar’s declaration, NOC Chairman Mustafa Sanalla immediately replied that only his company could trade Libyan oil on international markets. The U.S., the United Kingdom, France and Italy hastened to issue a joint communique expressing concern over “the transfer of control to an entity other than NOC.” The European Union declared that Libyan oil infrastructure must remain under the sole control of the NOC and that it would oppose any attempt to trade Libyan oil outside of officially recognized channels.

Revenue shares

Observers wondered about General Haftar’s motivation. Was it to stop the electoral process or to flex his muscles before the December vote? He had not tried to smuggle oil out of the country. It has been suggested that he wanted to pressure the GNA to exercise tighter control over the Central Bank of Libya and provide greater transparency about the distribution of oil revenues.

The CBL kept its prerogatives intact throughout the civil war and continues to handle all oil revenue from royalties, taxes and exports. The term of its governor, Sadiq al-Kabir, officially expired in 2015, but he remains at the helm and reportedly doles out funds not only to the Tripoli government but also to Islamic militias. There is no way to check; the CBL board of directors has not convened for years and nobody seems to know what is going on.

Supporters of the central bank head say he is enforcing a strict financial policy, but his critics say he is too close to Islamic militias.

Mr. al-Kabir’s supporters claim he is enforcing a strict fiscal and financial policy, protecting the value of the Libyan dinar and safeguarding the country’s currency reserves, presently estimated at $72 billion. However, the CBL governor is considered close to Islamic militias, which he finances, and the consensus is that he should be replaced.

Indeed, in October 2017 the Tobruk HoR appointed a universally respected expert, Mohammed Shoukry, to replace him. The authorities in Tripoli refused to confirm the appointment, however, since it had not been consulted according to the provisions of the 2015 Skhirat agreement.

This suggested that General Haftar was angling for a deal. He would be willing to reinstate the NOC if Mr. al-Kabir – whom he accuses of having helped Islamist groups to take over and blockade the oil terminals in June – was fired and replaced by Mr. Shoukry, who would set new criteria for distributing oil income.

The LNA commander was also expressing his displeasure at the Western countries, which were instrumental in appointing Mr. al-Sarraj as the head of the national government. They distrust General Haftar even though he commands the only effective army in Libya and protected the eastern part of the country and its oil ports from a takeover by Islamic militias.

Surprisingly, Fayez al-Sarraj, perhaps to appease his rival, asked the UN Security Council on July 11 to appoint an expert committee to supervise the CBL’s revenues and expenses. The Security Council responded positively and promised to examine the issue. General Haftar then withdrew his threat to export oil and fully reinstated NOC; Mustafa Sanalla took immediate steps to resume international sales. The Libyan Audit Bureau, which had been split in two in 2014, announced that it was working at reuniting the Tripoli and Beida CBL branches before drafting a unified operational plan for 2019.

France vs. Italy

The arms embargo imposed by the UN had led Khalifa Haftar to look to Russia for help. Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi, who supports General Haftar – the two men work together to defend their common border against terrorists and smugglers – facilitated contacts with President Vladimir Putin, who invited the general to Moscow and was only too happy to be handed a toehold in the country. Wounded LNA soldiers were given treatment in Russia while Spetsnaz commandos were dispatched to Libya’s border with Egypt to train General Haftar’s troops. Some feared that Russia would be allowed to set up naval bases in Libya.

France and Italy – the two EU countries most engaged in Libya – find themselves at loggerheads.

Meanwhile, France and Italy – the two EU countries most engaged in the Libyan quagmire – found themselves at loggerheads.

France, perhaps with the interests of its major oil company, Total SA, in mind, has been trying to restart the political process. French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian went to Libya in July 2018 and met separately with Fayez al-Sarraj, Khalifa Haftar, the two heads of parliament and military leaders to encourage them to stay the course, even contributing 853,000 euros toward organizing the elections. He also pledged assistance in training the unified Libyan army to be set up after the elections.

France has also been overt in its support for General Haftar, according him equal status with Prime Minister al-Sarraj.

Italy, which ruled Libya as a colony from 1911 to 1947, and whose oil and gas company Eni SpA has extensive oil and gas operations in the country, has taken an openly reluctant attitude toward elections. Foreign Minister Enzo Moavero Milanesi visited Libya soon after Mr. Le Drian, but remained noncommittal, stressing that the Libyan people and not any foreign power should decide when the country should hold elections.

In early August, the HoR declared Italian Ambassador Giuseppe Perrone persona non grata for allegedly urging that elections be postponed until national reconciliation is achieved. This allegation was denied by the embassy. Meanwhile, a spokesman for General Haftar was calling for a Russian intervention in Libya similar to the one in Syria to “directly eliminate foreign players such as Qatar, Turkey and Italy.”

The GNA reacted angrily, stating that “the course and date of Libya’s planned elections were a matter to be considered by the Libyans alone.” This did not stop Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte from reiterating on August 8 that there was “no hurry” to hold elections in Libya. He noted Libya’s strategic importance to Italy for historical, geographical and political reasons, stressing that his country was the main target for the immigrant flow from the Libyan coast.

Seeking consensus

Briefing the Security Council on July 16, the UN special envoy to Libya, Ghassan Salame (appointed in June 2017), expressed his doubts that the elections could be held on schedule. “Even the recent agreement to resume oil production will not hold unless key issues concerning the distribution of wealth and endemic plundering of resources are immediately tackled,” he said. Mr. Salame also expressed worry at the HoR’s reluctance to ratify the draft constitution and the electoral law ahead of the referendum.

In a keynote speech to the Oil and Fuel Theft Summit in Geneva in April, NOC Chairman Sanalla said that 30-40 percent of Libya’s fuel output was lost through theft or smuggling. He called for the EU’s Operation Sophia naval patrols to be expanded to combat smuggling of Libyan refined fuels.

Both sides of the conflict appear keen to preserve the oil sector while letting the NOC manage it prudently.

Both sides of the conflict appear keen to preserve the oil sector while letting the NOC manage it prudently; their main wish is for a fair division of revenues. Until a consensus is reached on this issue, it is understood that elections cannot be held.

Unfortunately, in the chaos that prevailed after Qaddafi’s fall, some minor and not-so-minor players have entrenched themselves in the oil-revenue stream. They will not readily relinquish their hold without some sort of compensation.

Assume the best

Khalifa Haftar may be the best-equipped man in Libya to tackle these issues. He must be counted as a strong contender for the presidency, but he will find it hard to defeat Mr. al-Sarraj – who has the full support of the West. Realizing this, the general may well decide to stop the electoral process – unless some kind of deal is struck, as is often the case in the Middle East.

Should he not be elected, General Haftar will be given command of the country’s unified army. His position will be further reinforced if the central bank gets an HoR-appointed governor who makes a new division of oil revenues. Apparently, this is why the HoR is stalling on the issue of ratifying the constitution and launching the electoral process.

According to latest Economic Outlook for Libya – published by the World Bank in April – the basic assumption is “that the political strife is resolved” and a unified government will launch a “comprehensive plan” to rebuild the country. Under this scenario, oil production will rise to 1.5 million barrels per day by 2020, while economic growth rebounds to 15 percent in 2018 and an average 7.6 percent in 2019 and 2020. Both sides are aware of this prospect, but will they listen to reason?

Even should elections be held on schedule, they may not bring the hoped-for reconciliation. Nevertheless, there is room for very cautious hope, born of an understanding by both sides that they are barely a step away from the abyss. As they know full well, resumption of the devastating civil war would spare neither side, while wreaking havoc on the volatile oil market.