Assessing geopolitical alignments in the Asia-Pacific

With tensions between the U.S. and China high, it is worth asking what the major players in the Asia-Pacific might do if push ever came to shove. Three main contingencies appear: Chinese aggression against Taiwan, a conflict in the South China Sea and an attack on Japan.

In a nutshell

- A conflict over Taiwan would make Japan and Australia step in

- Washington can mostly count on support from the United Kingdom

- Europe and India are less likely to stand up to Beijing

It is easy to theorize about future geopolitical alignments when it comes to China and the Indo-Pacific. The more practical question remains what those alignments will mean in any particular series of events. What follows are three major contingencies and how relevant power centers will likely react.

The Taiwan contingency

The United States has been the guarantor of Taiwan’s security for 70 years. It has successfully deterred a mainland move to unify the island under the banner of the People’s Republic of China by virtue of superior American firepower and consistent signaling of resolve. In recent years, however, this balance of force has begun to shift.

At the very least, the costs that the Chinese can impose on the U.S. for intervening may have risen to a level higher than Washington could sustain politically. Some experts now say the U.S. could be defeated outright. These prospects, mirrored in Beijing’s own estimates, make it increasingly plausible that Chinese President Xi Jinping will make good on his promises to settle the Taiwan question, by force if necessary.

If he attemts to use force, the U.S. will respond in kind. The risks of not countering such a move are too great. It would call into question American security guarantees around the world.

The U.S.’s most important ally in defense of Taiwan will be Japan. However, joining the fight would not be a straightforward decision for Tokyo, where it is a complicated domestic legal issue. Japan is only slowly preparing for such a decision. To the extent that it is planning a military response, it would be in concert with the U.S.

An outright assault on Taiwan will leave Japan no choice but to side with the U.S.

Much will depend on the circumstances. An outright assault on Taiwan’s main island will leave Japan no choice but to side with the U.S. diplomatically and operationally. A Chinese effort to take one of Taiwan’s outlying islands will present Japan with a trickier equation to solve. Yet even then, it will force Japan to speed up its preparations for conflict and drive it closer to the U.S. A successful unification of China and Taiwan, whether through invasion or pressure imposed by Chinese occupation of an outlying island, would leave Japan permanently vulnerable to Chinese designs on Japanese territory.

Australia is in a similar, albeit more distant, position. Its alliance with the U.S. is tight, and it has recently defied expectations that its economic relationship with China would loosen that bond. For the last two and a half years, Canberra has been vocal about several of its differences with China, including on the latter’s accountability for the spread of Covid-19.

In this case, too, an outright assault on Taiwan would compel Australia to take part in a U.S.-led military response. An attack on outlying islands intended to force a Taiwanese political capitulation would also lead to its military involvement. Australia, unlike Japan, does not have a political tradition of pacifism to constrain it.

Facts & figures

Beyond these allies, the U.S. cannot count on military support, except perhaps from the United Kingdom. Aside from the British and the French, European forces lack the capacity to meaningfully contribute in any regard. This, and Europe’s underdeveloped ties with U.S. forces in the Pacific will serve as an excuse for it to stand pat. Brussels and other European capitals will mostly respond with rhetoric and diplomatic statements, while an economic response – sanctions or suspension of economic exchanges – is an outside possibility.

This will be the case in the event of an outright assault on Taiwan. Anything less, particularly if Taipei somehow precipitates it, will cloud the European response, even diplomatically. India’s response will be roughly the same as Europe’s in intensity in either case. The response from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and its member countries will be even less direct, although military facilities in Singapore will be at the U.S.’s disposal.

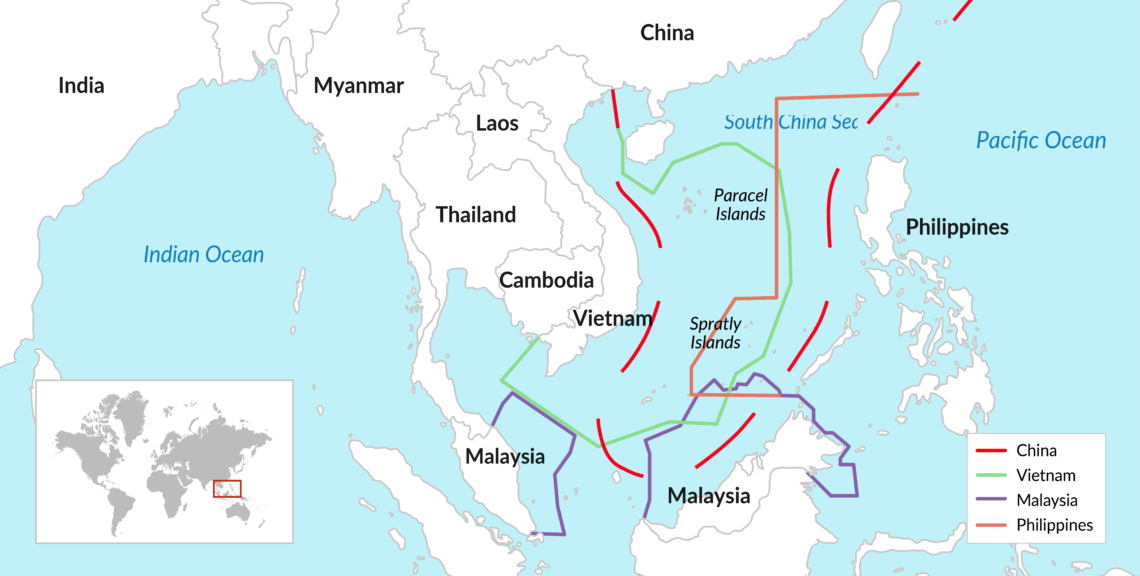

The South China Sea contingency

A military conflict in the South China Sea could arise from several different scenarios. The most likely would be an inadvertent incident between American and Chinese naval or air forces that spirals into a more complex military engagement. The U.S. is well prepared to avoid such an escalation. It is unclear, however, whether the Chinese are also ready, and recent tensions between the U.S. and China have impeded joint efforts to control for such events.

The second scenario involves the Chinese reacting unexpectedly aggressively to routine U.S. operations such as close-in surveillance near Chinese shores or freedom of navigation exercises.

The third scenario would involve the Chinese moving to seize an island not currently under its control, followed by a bolder U.S. reaction than Beijing expects. Given U.S. security commitments to the Philippines, this is particularly plausible in response to any move on territory disputed between China and the Philippines. In any of these eventualities, other capitals will respond similarly as to a Chinese move on Taiwan’s outlying islands.

European capitals will express concern over the violation of laws of the sea; Brussels will struggle to formulate a clear statement.

Tokyo will be prepared to contribute if necessary, but will pray not to be asked. However, any conflict precipitated by China would result in a future U.S.-Japan alliance that is operationally tighter. Japan would increase its coordination with the U.S. diplomatically and intensify its own diplomatic engagement in Southeast Asia. Australia would contribute to the U.S. response as necessary.

European capitals will express concern over violations of laws of the sea, while Brussels will struggle to formulate a clear statement that attributes blame appropriately. European economic retaliation against China is less likely than in the Taiwan case. Brussels or another European capital may even presume to mediate the conflict.

New Delhi, in the event of escalation around either incidental U.S.-China contact or purposeful Chinese reaction to routine U.S. operations, will obliquely side with Washington. India’s position on some of the underlying legal issues involving military operations at sea contradicts U.S. policy. Beijing knows this fact and will exploit it. In the event of Chinese aggression, India will more forcefully condemn China.

In none of these three scenarios, however, will India deploy forces to the region to assist the U.S. The prospects for disputes on its land border with China and fear of entrapment by too closely aligning with the U.S. will preclude India from doing more.

As for ASEAN, in the first two scenarios, it will sit on the fence, with military facilities in Singapore still at the U.S.’s disposal. Depending on the government in the Philippines at the time, Manila could also be supportive of the U.S. diplomatically. In the third scenario, ASEAN would be paralyzed, and in the face of an attack on one of its members, that paralysis will threaten the organization’s very existence.

The China-Japan contingency

The most likely conflict scenario in this case involves Japanese territory in the East China Sea claimed by China. The U.S. would get involved because of American treaty commitments to Japan and the American military presence there. For more than 10 years, Beijing has been physically challenging Japanese sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands (known as the Diaoyu Islands in China). Today, China’s coast guard routinely patrols waters just outside Japan’s territorial seas near the islands, and regularly sails into them.

Facts & figures

There are two likely paths to military conflict in this situation: isolated contact between the two countries’ coast guards that escalates into broader armed conflict, and a push by Chinese paramilitary forces that spirals into general contact between the two countries’ navies. A third scenario, centered on a Chinese seizure of one of the islands, is unlikely under current circumstances.

In either of the first two cases, once the Japanese military is engaged, the U.S. would be drawn into conflict with Chinese forces. U.S. treaty commitments would be invoked in these cases, as well as in the direct third scenario. As in the case with Taiwan, Washington’s failure to respond would sever the country’s entire network of alliances, especially in the Indo-Pacific. Australia’s military, bound to the U.S. by a security treaty and alarmed by aggression against a close security partner in Japan, would also mobilize.

The UK would be much more assertive in this contingency than in the other two. It has made Japan its principal security partner in the region and its navy is already far more closely integrated with U.S. naval forces than that of any other European country. London is also the most critical of China among European capitals and is aligned substantively with U.S. positions across several issues. This would mean a forceful diplomatic response from London, an economic response, and, depending on the scale of the conflict, the contribution of British military assets.

The rest of Europe would be more reticent, but more active than in either of the previously discussed contingencies. Japan is a significant power with a long history in Europe. It is the European Union’s largest trading partner in Asia after China and one of its biggest investors.

The most consequential alignment concerning the China challenge is among the U.S., Japan and Australia.

Although France has prioritized strategic partnership and security cooperation with Japan, the relative lack of interoperability between its forces and American forces in the Indo-Pacific (compared with U.S.-UK interoperability), would constrain its military contribution. Its traditional Gaullist reluctance to follow Washington’s lead would also contribute to this reticence. France’s diplomatic response would likely be forceful, however, and it would attempt to rally other European capitals to the cause. Brussels’ response would be more favorable to the U.S.-Japan response in this contingency than it would be to the U.S. in either the Taiwan or South China Sea scenarios.

Like Europe, India’s diplomatic response would be emphatic. Japan-India relations have grown considerably closer in recent years, including on security matters. The resurrection of the quadrilateral security dialogue and India’s active participation therein has consciously signaled the priority it places on the relationship.

Southeast Asia – perhaps counterintuitively, given its hesitancy to stand up to China closer to home in the South China Sea – would likely take Tokyo’s side in such a conflict. Japan’s close relationships with ASEAN, its sizable economic interests there and its general popularity in Southeast Asia would work in its favor.

Scenarios

Several conclusions about alignments in the Indo-Pacific can be extrapolated from the above assessments:

- First, there is no overarching alignment of interests or values that consistently predicts how major centers of power will respond in the event of a destabilizing conflict involving China.

- Second, the most consequential alignment against China is among the U.S., Japan and Australia. The three partners still have a long way to go in bringing India into alignment.

- Third, except for Singapore, Southeast Asia should be considered nonaligned. The U.S.-Philippines security alliance is about the defense of the Philippines, not strategic alignment.

Finally, Europe, except for the UK, should be considered only slightly favorable to Washington in the U.S.-China power equation.