European Central Bank torn between policy and politics

With the governing body of the ECB bitterly divided over monetary policy, new President Christine Lagarde faces an extraordinary challenge of putting Europe’s most important financial and regulatory institution back on an even keel.

In a nutshell

- ECB decision makers are divided over its mandate and policies

- Draghi's controversial legacy makes his successor’s task significantly harder

- Christine Lagarde may be inclined to stick to the ECB’s monetary course

This new series of GIS reports examine how effectively countries are ruled and the consequences of governing systems for economies, societies, and nations’ development prospects.

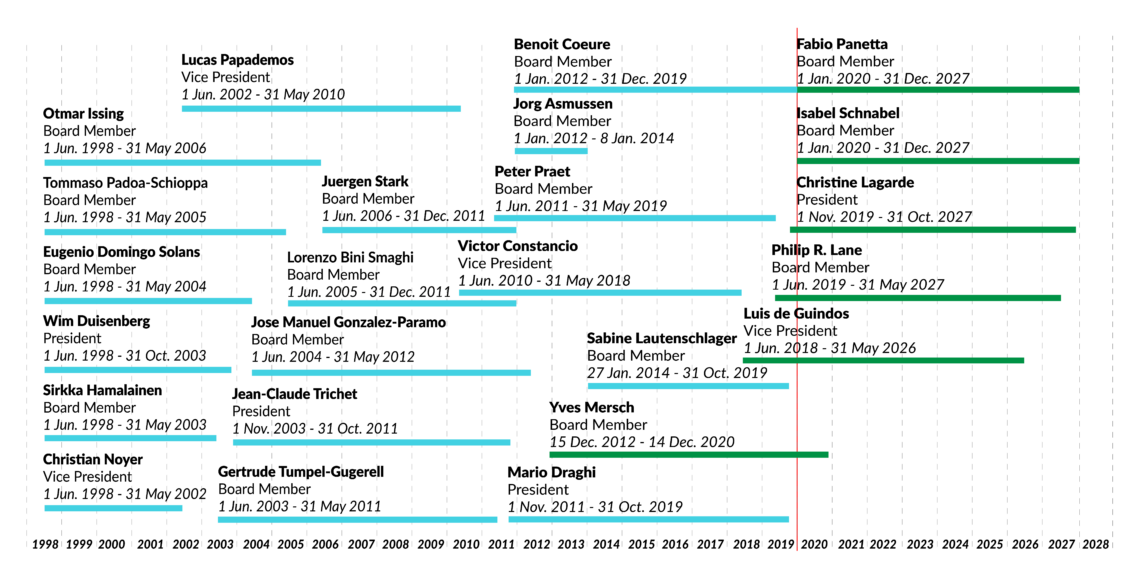

On November 1, 2019, Christine Lagarde started her eight-year mandate as president of the European Central Bank (ECB). The legacy her predecessor Mario Draghi has left is impressive yet double-edged.

On the one hand, Mr. Draghi’s unconventional crisis management has transformed the Frankfurt-based bank into one of the world’s most powerful institutions of global economic governance. For years, the former president’s name stood for trust and commitment to do “whatever it takes” to sustain the eurozone. Throughout his term, Mr. Draghi had launched a series of large-scale asset purchases and nonstandard lending operations, one more ambitious than the other, aiming to combat deflationary pressures and boost growth and investment in the European Union. Also, under his guidance, the ECB set up the Single Supervisory Mechanism that today directly oversees the eurozone’s 119 largest banks and indirectly all the others, making the ECB the number-one player in the European banking sector.

On the other hand, by inheriting the previous president’s agenda, Ms. Lagarde must also deal with a range of operational and managerial challenges. The reportedly understaffed institution, facing an ever-increasing workload, is threatened with a burnout crisis involving a large share of its 3,600 ECB employees. The central bank’s steadily growing balance sheet, which following years of massive bond-buying has reached a vertiginous 4.7 trillion euros (around 41 percent of the eurozone’s gross domestic product, or GDP), is another volatile issue. The adverse effects of such drastic balance sheet expansions on how the financial market functions are not yet known, as the Bank of International Settlements emphasizes.

The last straw

More importantly, the ECB Ms. Lagarde takes over appears deeply divided, up to its top echelons, over what postcrisis monetary policy has achieved so far and how it should evolve in the future. For the first time in its 21-year history, the ECB appears to face an internal revolt. It was triggered by Mr. Draghi’s last decision (announced on September 12, 2019, just weeks before his departure), to restart quantitative easing (QE) for an “extended period of time” by purchases of new bonds at a monthly rate of 20 billion euros, and to cut interest rates further into negative territory (from -0.4 percent to -0.5 percent).

More than a third of Mr. Draghi’s colleagues on the 25-member Governing Council fiercely contested not only the decision itself (which they considered a “disproportionate” response to the present economic situation), but also the way the policy decision was imposed by the outgoing president, putting the council before a fait accompli. Some complained that they had been given only a few hours to reflect on such a far-reaching stimulus package and felt the governing body had not had much of a say on the matter.

The ECB misinterprets its original mandate to preserve price stability, the signatories of the memorandum argue.

In his last days in office, Mr. Draghi’s lone-wolf leadership ended up frustrating not only the ECB’s hawks, such as the central bank chiefs of Germany (Jens Weidmann), the Netherlands (Klaas Knot) and Austria (Robert Holzmann), or Executive Board member Sabine Lautenschlaeger, who even resigned in protest.

More moderate Council members (France’s central bank governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau and Executive Board member Benoit Coeure, for example), who usually supported Mr. Draghi’s cheap-loan policy, expressed their concerns as well.

After the September 12 meeting, one of the few officials to publicly defend Mr. Draghi’s farewell stimulus was the ECB’s new chief economist Philip Lane – except that to his taste, the announced new policy was still not expansionary enough.

Resistance faction

On October 4, 2019, a group of former policymakers from Germany, France, Austria and the Netherlands, led by ECB senior figures Juergen Stark and Otmar Issing (the bank’s first chief economist), joined the fray by publishing a memorandum sharply critical of the ECB’s “ongoing crisis mode” and, in particular, Mr. Draghi’s ultimate revival of QE. The former central bankers think it is based on a “wrong diagnosis” and could lead to severe side effects that risk reactivating financial instability in Europe.

The ECB misinterprets its original mandate to preserve price stability, the signatories of the memorandum argue. More worryingly, monetary policy has increasingly become embroiled with politics. The authors even suspect that behind Mr. Draghi’s recent decision “lies an intent to protect heavily indebted governments from the rise of interest rates” – a hidden form of “monetary financing,” explicitly prohibited by EU treaties that define the ECB’s mandate.

Facts & figures

Some journalists push the argument further and speculate that the final-curtain QE package might have been Mr. Draghi’s parting gift to Italy, which today owes over 2.06 trillion euros in public debt. When asked whether he could be running for president in his home country after leaving the bank job, the departing ECB boss derisively replied: “Ask my wife.”

Monetary obstinacy

The old guard also points out that ever since it started QE, the ECB has regularly undershot its self-imposed inflation target of “close-but-below 2 percent.” Since 2015, monthly inflation rates reached (actually: overshot) the target only once (2.2 percent in July 2018), which was due to a temporary surge in energy prices. According to the bank’s revised macroeconomic projections, annual eurozone inflation for 2019 and 2020 will not exceed 1.2 percent and 1.0 percent, respectively.

At the end of the Draghi era, growth predictions are not less morose: 1.1 percent for 2019 and 1.2 percent for 2020. In comparison, in 2014, only a few months before the ECB launched its emblematic Asset Purchase Programme (APP), which in less than four years channeled more than 2.6 trillion euros of liquidities into the economy, the euro area’s annual growth rate stood at 1.42 percent. The ECB misinterprets its original mandate to preserve price stability, the signatories of the memorandum argue

At this stage, Ms. Lagarde could not drive back the policy, at least in the short run, even if she wanted to.

So much stimulus for so little effect? Why persevere in a policy that did not produce the desired results? Today, Mr. Draghi’s legendary “never-accept-failure” maxim, reiterated in his farewell speech, no longer convinces; to some of his most fervent critics, rather than resilience, it reflects an attitude of “monetary insanity.”

Delicate moment

Ms. Lagarde starts her term with her hands tied in the context of a looming recession. By reopening the loose-money-tap just before leaving, her predecessor set her up for a difficult start. At this stage, she could not drive back the policy (at least in the short run), even if she wanted to. Monetary policy needs to be predictable to anchor expectations. The ECB’s credibility is at stake.

Nonetheless, one of the problems with an “overextended” monetary policy is that more and more needs to be done to achieve less and less. As Olivier Blanchard, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), warns, the ECB might soon run out of ammunition. Quality bonds (especially safe sovereign debt) are becoming hard to buy in Europe and interest rates have already fallen under the zero lower bound (a macroeconomic situation that occurs when the short-term nominal interest rate is at or near zero, causing a liquidity trap and limiting the central bank’s capacity to stimulate economic growth).

Reversal point

If pushed too deeply into negative territory, rates might end up depressing rather than stimulating the economy, claim economists Markus Brunnermeier and Yann Koby. At one point, the intended effect of ultra-loose policy can be “reversed” and become “contractionary,” they explain. The policy rate the authors refer to as the “reversal interest rate” corresponds to the “effective” lower bound – which the ECB seems close to reaching if we are to believe the aforementioned group of former European rate-setters.

Worse, interest rates have lost their “steering function,” the latter warn. They predict that if a major crisis strikes, it will be of very different dimensions than those we have seen before. All the more so, as there seems hardly any maneuvering room left for the central bank to ease monetary policy further.

However, if the ECB admitted these truths explicitly, markets could “freak out,” Mr. Blanchard fears. For the moment, Ms. Lagarde’s various declarations indicate she is willing to stay on the path of accommodative policy – as long as firepower is left. Supposedly, she will rely on the recommendations of her chief economist, Mr. Lane, whose enthusiasm for “super-easy” monetary policy has never waned.

In the face of sudden deflationary threats, the 2 percent threshold is maintained, but the purpose now is to spur inflation.

As the former managing director of the IMF, whose research team has produced pioneer work on how to “enable” deep negative interest rates, Ms. Lagarde may be far more confident than conservative central bankers of the possibilities of operating with very low rates.

There may be a limit to how deep rates can fall below zero, the ECB head asserted in a recent interview for the Financial Times, but she is convinced we are not there yet.

Facts & figures

The European Central bank, its history and governing system

The European Central Bank (ECB) has been responsible for conducting monetary policy for the euro area since January 1, 1999.

The euro area (eurozone) was created by transferring the responsibility for monetary policy from the national central banks of 11 European Union (EU) member states to the ECB in January 1999. Greece joined in 2001, Slovenia in 2007, Cyprus and Malta in 2008, Slovakia in 2009, Estonia in 2011, Latvia in 2014 and Lithuania in 2015.

The creation of the eurozone and a new supranational institution, the EU central bank, was a milestone in the extended process of European integration.

As a condition for joining the euro area, the 19 countries had to meet the so-called convergence criteria. The criteria set out the economic and legal preconditions for countries to participate in the Economic and Monetary Union. The remaining EU member states, except Sweden and Denmark, are expected to join the Monetary Union eventually, but no dates have been set for that.

Mission

The European Central Bank and the national central banks together constitute the Eurosystem, the central banking system of the euro area. The main objective of the system is to maintain price stability: safeguarding the value of the euro.

The European Central Bank is responsible for the prudential supervision of credit institutions located in the euro area and participating non-euro area member states within the Single Supervisory Mechanism, which also comprises the competent national authorities. It is supposed to guard the safety and soundness of the banking system and the stability of the financial system within the EU and each participating member state.

Decision-making

The Governing Council is the main decision-making body of the ECB. It consists of the six members of the Executive Board, plus the governors of the national central banks of the 19 eurozone countries. Its main responsibilities are:

- Establishing the guidelines and making the decisions necessary to perform the tasks entrusted to the ECB and the Eurosystem

- Formulating monetary policy for the euro area. This includes the decisions related to monetary objectives, key interest rates, the supply of reserves in the Eurosystem, and the establishment of guidelines for the implementation of those decisions

- Making decisions in the context of the ECB’s banking supervision responsibilities, and drafting decisions on policies proposed by the Supervisory Board under the non-objection procedure.

The Executive Board consists of the president, the vice president and four other members, all appointed by the European Council, acting by a qualified majority. Its responsibilities include:

- Preparing Governing Council meetings

- Implementing monetary policy for the euro area under the guidelines specified and decisions taken by the Governing Council; in this capacity, giving the necessary instructions to the euro area national central banks

- Managing the day-to-day business of the ECB

- Exercising certain powers delegated to it by the Governing Council; these include some of a regulatory nature.

The General Council comprises the president and vice president of the ECB, and the governors of the national central banks of the 28 EU member states – the 19 eurozone countries and the nine countries that have not adopted the common currency yet. The other members of the ECB’s Executive Board, the president of the EU Council and one member of the European Commission may attend the meetings of the General Council but do not have the right to vote.

The General Council was established as a transitional body. It carries out the tasks that the ECB is required to perform in Stage Three of Economic and Monetary Union because not all EU Member States have adopted the euro yet.

By the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and the ECB, the General Council will be dissolved once all EU member states have introduced the single currency.

The Supervisory Board meets every three weeks to discuss, plan and carry out the ECB’s supervisory tasks. It proposes draft decisions to the Governing Council under the non-objection procedure. Its members are:

- Chair, appointed for a nonrenewable term of five years

- Vice-chair, chosen from among the members of the ECB’s Executive Board

- Four ECB representatives

- Representatives of national supervisors.

If the national supervisory authority designated by a member state is not a national central bank, the representative of the competent authority can be accompanied by a representative from that country’s central bank. In such cases, the representatives are together considered as one member for the voting procedure.

Paradigm shift

At a time of heated disagreements, calming tempers, reviving team spirit and trying to rebuild trust and consensus within the institution are the new ECB chief’s first tasks. For this part of the job, Ms. Lagarde has strong credentials. The media worldwide acclaim her outgoing and friendly personality, her exceptional leadership skills, her diplomatic and communicational talents acquired in French politics, and the IMF. She took over the latter institution at a critical moment – after the Strauss-Kahn scandal – and restored the shine to its reputation.

First and foremost, President Lagarde will propose to review the ECB’s monetary policy framework. The last strategy review, conducted in 2003, set control of inflation at the heart of the central bank’s mission. It merely reiterated a definition of price stability put forward in 1998 by the ECB’s first Governing Council. It considered as ideal an average annual increase in the price level of “below-but-close to 2 percent.”

Back then, monetary policy was all about taming inflation. Since the 2008 crisis, in the face of sudden deflationary threats, the 2 percent threshold is maintained, but the purpose now is to spur inflation.

As said before, in the last decade, inflation rarely came close to the reference value. The question Ms. Lagarde is likely to examine is whether the ECB should reduce the 2 percent target to put an end to the chronic failure of post-crash inflationary policy. Maybe “adapting policy to a new world” implies accepting that inflation has become a less meaningful economic indicator, as suggests a recent report published by The Economist.

Why, indeed, put the economy at risk – after all, a “world of perpetual QE” is one that fuels asset-market bubbles, zombie firms and debt overhangs, which hold back growth for years – for the sake of a target that may not be relevant?

The renewal of two-thirds of the Governing Council (in the ECB’s Executive Board alone, five out of six members will have been replaced between June 2019 and December 2020) may allow Ms. Lagarde to rethink the bank’s key goals.

It’s mostly fiscal

A probable scenario is that Ms. Lagarde will turn to fiscal policy, thereby drawing on her experience at the IMF – the world’s biggest stimulus machine, nicknamed, not for nothing, “It’s Mostly Fiscal.”

Importing the IMF’s (not always assumed) Keynesian paradigm into the ECB might be a big step, but the idea has been in the air among EU economists for some time. “Monetary policy needs help from fiscal policy,” insists Mr. Blanchard, the former IMF economist. Mr. Draghi himself seeks to explain the failure of his inflationary strategy in these terms, claiming that the burden of macroeconomic adjustment “has fallen disproportionately on monetary policy.”

IMF researchers have advanced in a recent paper a novel idea of redistributive measures induced by the central bank.

Toward the end of his tenure, he urged for rapid completion of the Economic and Monetary Union through the creation of a common “fiscal capacity” (a eurozone ministry of treasury and finance). That would give the ECB a direct fiscal counterpart, freeing it from the complexity of operating in a system with 19 fiscal preferences that are far from being synchronized.

Those assuming that such a far-reaching reform of the EU could become a reality, including the new head of the IMF Kristalina Georgieva, are expecting Ms. Lagarde to get countries like Germany and the Netherlands to revitalize the faltering eurozone economy through large-scale domestic investment. In particular, Berlin’s famous fiscal prudence is accused of hamstringing the ECB’s monetary stimulus.

Scenarios

Exerting pressure on member states’ fiscal policies is one stratagem by which the ECB might enlarge its outreach.

There are also hints that the bank could insert itself into the territory of fiscal policy. One way of doing this could be directing its asset purchases toward green bonds (earmarked to be used for climate and environmental protection projects; “green-QE” is an option already envisaged by Ms. Lagarde). Another is transferring money directly into citizens’ bank accounts to encourage spending; the concept of “helicopter money” has recently cropped up in ECB-policy-making circles. Still another way could be subsidizing modest savers for losses incurred by negative interest rates – IMF researchers have proposed the idea of central bank-induced redistributive measures.

Blurring the boundaries between monetary and fiscal policy is, however, not anodyne. When the ECB was created in 1998, decoupling the two had been considered a cornerstone of the central bank’s independence and, ultimately, its legitimacy. Twenty years later, the ECB becomes increasingly politicized. It is undergoing ever more consequential operational, institutional and, all the more so, ideological shifts that put at risk its apprized independence.