EU-China relations at a crossroads

For decades, relations between the EU and China have been based on growing economic cooperation and trade. While Beijing moves toward a knowledge-based economy, it also sees the future in nationalist, “back-to-the-future” colors.

In a nutshell

- Chinese trade and investment is increasingly vital to the EU, especially its poorer states

- In the EU’s China policy, national priorities often overshadow collective interests

- Recently, however, Brussels has tried to adopt a more assertive approach to Beijing

Over the past few years, relations between the European Union and China have changed significantly. They now reflect the increasing ambivalence of the bilateral relationship and a global shift in the balance of power. Besides the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), factors that have prompted the EU to reevaluate and redefine its relations with Beijing include China’s perceived “debt-trap” strategy to make poorer countries economically and financially dependent, its growing investments in Europe’s critical infrastructure and core technologies (such as wireless 5G networks), and its tendency to ignore international law (by not accepting the binding arbitration ruling on its territorial claims in the South China Sea).

Europe’s goal is to defend its technological sovereignty and new industries by preserving fair competition. This is no easy challenge when faced with China’s state-owned companies and mercantilist strategy, which subsidizes Chinese investments on foreign markets while restricting foreign access to its home market.

Bilateralism vs. reciprocity

The growing Chinese investment presence in poorer European countries and key future industries, often linked with BRI infrastructure projects, has opened new fault lines within the EU’s 28 member states. To advance its goals, China prefers bilateral diplomacy to sidestep EU institutions. Despite a general acknowledgement among EU members that their global economic and geopolitical interests are best defended at the Union level, particularly against an emerging colossus like China, in practice the member states often pursue short-term priorities at the expense of longer-term, collective interests.

Last April, the European Commission downgraded China from a “strategic partner” (the designation in previous documents) to a “negotiating partner” in its latest strategic outlook on the country. It increasingly perceives China as an “economic competitor” in the global race for technological leadership and even as a “systemic rival” promoting an alternative model of autocratic governance. Chinese policies are seen as undermining the EU’s own foreign, security and economic policies, along with its long-term objective of fostering sustainable economic development, democracy and the rule of law.

Accordingly, EU institutions and member states have defined reciprocity as the guiding principle in their future relations with China. Any benefits must be mutual, including better access and fair competition on the Chinese home market. As French President Macron recently declared, the “period of European naivete is over.” But even so, when the second BRI forum was held in Beijing at the end of April, no fewer than 12 European heads of government were in attendance.

Facts & figures

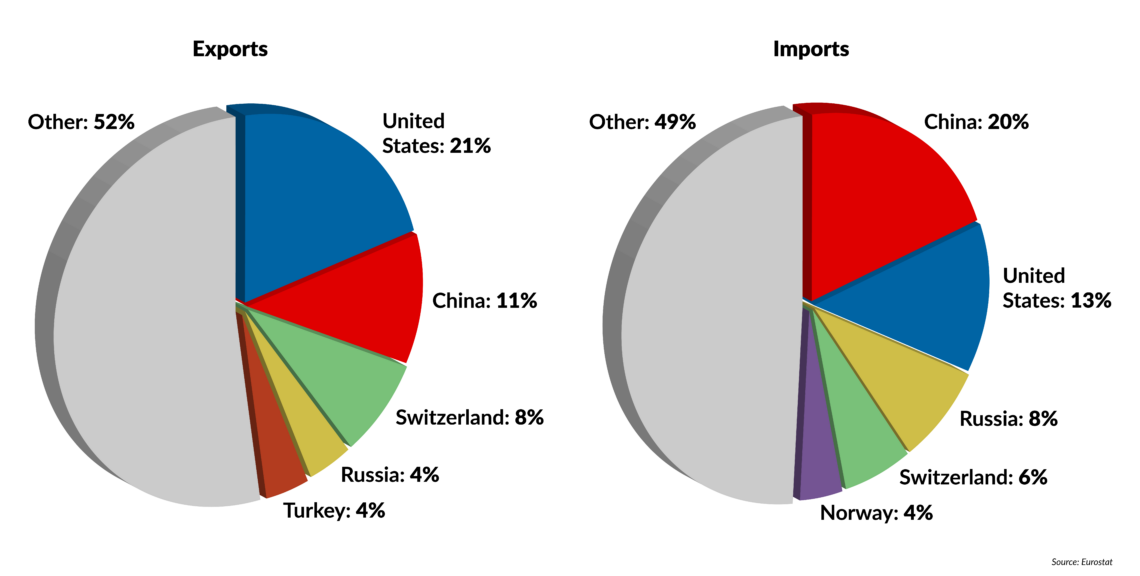

China among the EU-28's main trading partners for goods, 2018

Scenario 1: Growing divisions

The policy splits that already exist in Europe over China policy may only deepen as the significance of trade and investment from that country grows. China is already the EU’s second-largest trading partner, after the United States. If developments over the past few years are any guide, even the new, more assertive attitude adopted by Brussels toward Beijing will do little to change this strategic trend.

To take a recent, glaring example, on the same day (March 22) the European Council met to discuss strategy toward China before the April 9 EU-China summit, the Italian government signed new agreements to expand trade and investment ties with China. Perhaps the most important was a memorandum of understanding that made Italy the first G7 member to become a partner in the BRI, signed without prior consultation with Brussels.

Facts & figures

17+1 Group

- Originally called 16+1, this Chinese initiative enlisted 11 EU member states from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and five Balkan countries to promote investment and trade with China, particularly in coordination with the BRI

- On the European side, the founding members include Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia

- The group has met annually since its 2012 inaugural summit in Warsaw. The latest summit was held in Dubrovnik, Croatia

- Greece became the group’s 17th European member in August 2018

Through its “17+1” regional cooperation framework, Beijing has already succeeded in playing individual EU states against each other. China’s government has promised countries hit hardest by the global and European financial crisis – such as Greece and Portugal – large financial support and investment packages. In Greece, the state-supported Chinese shipping conglomerate COSCO has acquired a 67 percent in the port of Piraeus. In Serbia, Beijing is providing 2 billion euros in financing for a high-speed railway between Belgrade and Budapest, part of a wider Trans-Balkan rail network that will link up with the BRI’s seaborne component, the Maritime Silk Road.

As the foregoing makes clear, China is accelerating infrastructure projects in Southeastern Europe as part of a larger regional plan with clearly defined strategic interests. So far, this expansion has been relatively unimpeded by the EU, whose navel-gazing and Eurocentrism have prevented a vigorous push to integrate this traditional “poorhouse of Europe” more closely with the more advanced European economies. Instead, as lack of opportunity and mass emigration weaken the Western Balkans countries, the EU’s economic and geopolitical influence in the region has suffered.

Russia and China have exploited this geopolitical vacuum to expand their economic and political influence in Europe’s “soft underbelly.” Increasingly, this penetration is undermining the EU’s common foreign policy toward China. In July 2016, for example, a relatively harsh EU statement on aggressive Chinese practices in the South China Sea was blocked by Croatia, Greece, Hungary and Slovenia. And in 2018, the wording of an EU review of third-country investment in strategic sectors was watered down on the insistence of the Czech Republic, Greece, Malta and Portugal. Such incidents may multiply as the EU’s growing financial crisis makes it more difficult to achieve consensus and China’s ascent as the new global superpower continues.

Another example of European fecklessness can be seen in the European Commission’s long-awaited position paper on the challenge posed by China’s BRI. But this document, “Connecting Europe and Asia – Building Blocks for an EU Strategy,” nowhere mentions Beijing’s enormous infrastructure project or outlines a concrete response. Instead, it outlines a framework for basic economic and institutional norms, along with principles for its connectivity strategy. There seems to be a conscious effort to avoid looking at the EU’s infrastructure and connectivity proposals as a zero-sum alternative to China’s BRI. Even so, this EU strategy clearly reflects political weakness and growing – if unspoken – concern about China’s intentions.

With the EU failing to act as a unified political bloc, the chances are limited of getting China to abide by a neutral settlement mechanism based on international law to resolve BRI-related investment disputes. Instead, China will push for these cases to be put under the jurisdiction of new international commercial courts, based on existing Chinese judicial, mediation and arbitration procedures.

Scenario 2: Recognizing long-term interests

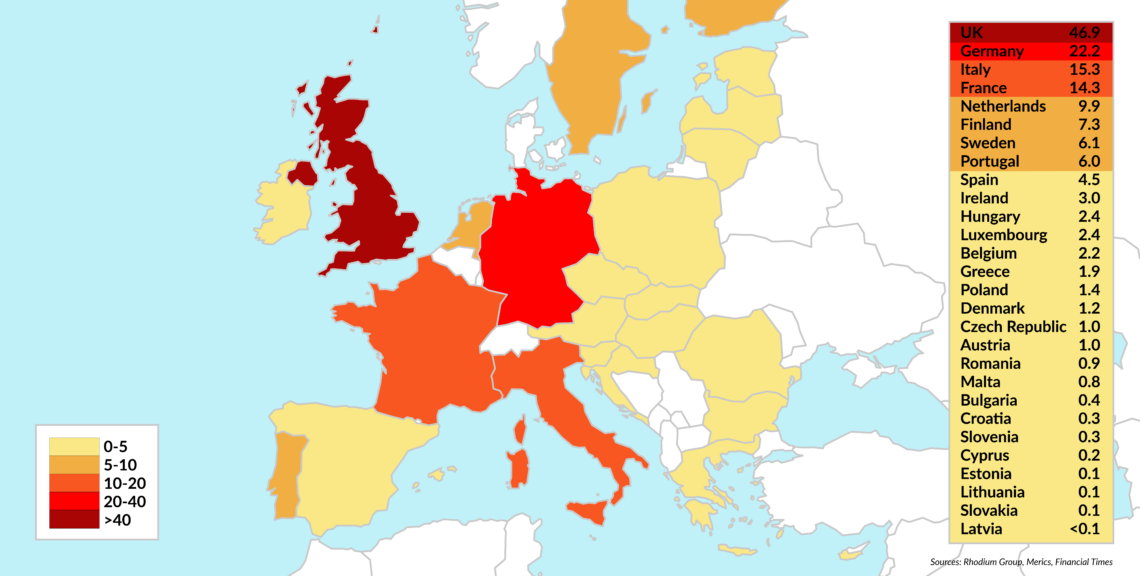

In this scenario, the EU would not just acknowledge the Chinese challenge but live up to its pledge to adopt a unified approach toward Beijing. A more assertive tone is already noticeable in some official statements and policies. Perhaps even more important, the astonishing inflow of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) into the EU, which rocketed from $840 million a year in 2008 to $42 billion in 2017, slowed sharply last year to $22.5 billion.

Over the past five years, the biggest chunk of Chinese FDI in Europe has gone to the energy sector (28 percent). About 60 to 70 percent of this investment has come from the China Investment Corporation (the country’s sovereign wealth fund) and state-owned enterprises. But even investments by private companies usually involve some government cooperation or support, which only deepens the EU’s security concerns.

As of 2017, China’s BRI-related investments in 16+1 countries were estimated at $9.4 billion. Half of this total was targeted at the West Balkans states of Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia, which belong to Europe’s smallest and economically weakest countries. Even so, many of the initial hopes for more trade and investment within the expanded 17+1 framework have already been disappointed. There have been critical discussions and reviews of Chinese investments and loan packages granted to these countries.

Facts & figures

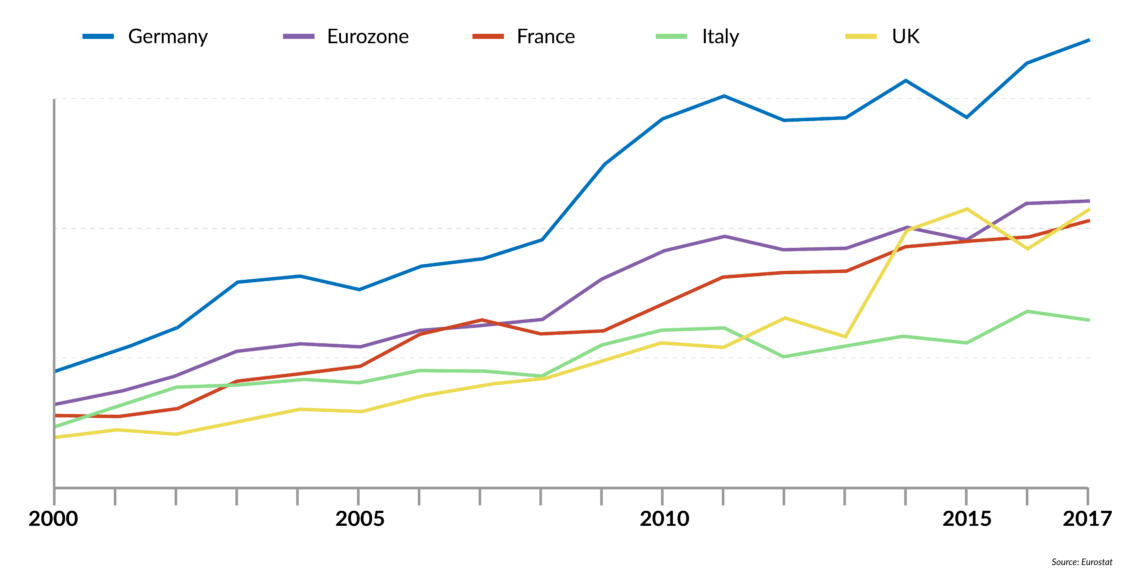

EU exports to China

(share of goods exports to non-EU countries)

Even more concern and mistrust has been stirred by China’s “digital silk road” strategy – especially investments in overseas fiber optic cables, 5G wireless communications and internet infrastructures, data and cloud computing services, global positioning and smart city sensors. By inserting backdoor viruses and mechanisms, Chinese suppliers could provide powerful tools for industrial and military espionage, propaganda and influence operations all over Europe. In the longer term, Beijing is suspected of trying to export its model of unrivaled internet censorship and comprehensive political control of data collection and traffic.

For the EU and other Western countries, these digital investment projects challenge human rights that form the constitutional basis of liberal democracies, especially personal freedom and data privacy. The dilemma for BRI cooperation countries is whether they are willing to trade Chinese investment in high-tech infrastructure for the type of Orwellian censorship and control that Beijing practices at home.

Facts & figures

Chinese investment in EU countries, 2000-2018

(cumulative total, in billion euros)

Chinese investment in critical infrastructures and takeovers of European high-tech companies will be reviewed more critically in the light of Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” program – a 10-year plan to transform the country into a dominant power in 10 cutting-edge industries. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), China still ranks 59th out of 62 countries surveyed in terms of openness to foreign investment.

This low ranking is mainly due to regulatory and other restrictions on market access, which are part of Beijing’s wider protectionist policies. China’s new foreign investment law in principle widens access for foreign investors and lifts requirements to share their technological know-how. However, in 48 sectors of key strategic interest, the restrictions and scrutiny mechanisms are maintained. Despite repeated assurances from the Chinese government, the frequency of enforced technology transfers to guarantee access to the Chinese markets has doubled over the past two years and looks set to keep rising.

Controlling investment

Germany has toughened its legislation on non-EU investors acquiring significant stakes in companies in sensitive strategic industries and critical infrastructure such as defense, energy and telecommunications. The new regulations allow the government to review and potentially block purchases of stakes as low as 10 percent, compared with the previous threshold of 25 percent. One Chinese acquisition that has been successfully blocked was that of Leifeld Metal Spinning AG, a machine tool company whose nuclear and rocket technology has military applications. Berlin also prevented China from purchasing 20 percent of 50Hertz Transmission GmbH, which would have given Beijing direct access to the German national power grid.

For German industry and government, the problem is not just controlling Chinese investments in domestic producers of robotics or artificial intelligence systems, or even in preventing theft of technologies, patents or other intellectual property. The larger issue is whether Europe can retain control over its own economic development and continue to wield power in global governance structures.

By contrast, supporters of free trade in the EU (notably Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden), fear new forms of protectionism that will ultimately hurt the EU by creating new barriers to investment. Smaller and economically weaker EU countries have already demanded compensation from Brussels for investments lost due to restrictions placed on China. But this ignores that many projects promised by China were never implemented or failed. This less-than-stellar track record will strengthen critics of EU naivety toward China, and could potentially help boost the bloc’s unity and assertiveness.

Italy’s newly signed MoU with China outlines a very ambitious plan to expand bilateral trade and investment (which amounted to just $16 billion since 2000), particularly given Italy’s public debt burden of 130 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). But the total commercial package was quite modest at $2.8 billion, or reportedly eight times less than Airbus’s deal with China a few weeks earlier. Even so, the 29 bilateral agreements could generate trade commitments of more than $20 billion.

Notably, Italy’s deal with China omits cooperation and investment in the telecommunications sector. As in other European countries, Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei had aggressively targeted Italy for major investments in 5G wireless networks. Further action in this area has become another litmus test of the EU’s ability to formulate a common position on China, particularly in light of U.S. demands to block Huawei’s access to 5G networks on cybersecurity concerns.

For now, most EU member countries are unwilling to freeze out Huawei and other Chinese companies entirely. This reluctance stems from China’s increasing edge in 5G technologies and the EU’s faltering consensus on the nature of the Chinese security threat. Even so, the United Kingdom, Germany and several other European countries appear ready to shut out Chinese investments in at least a few key sectors.

Facts & figures

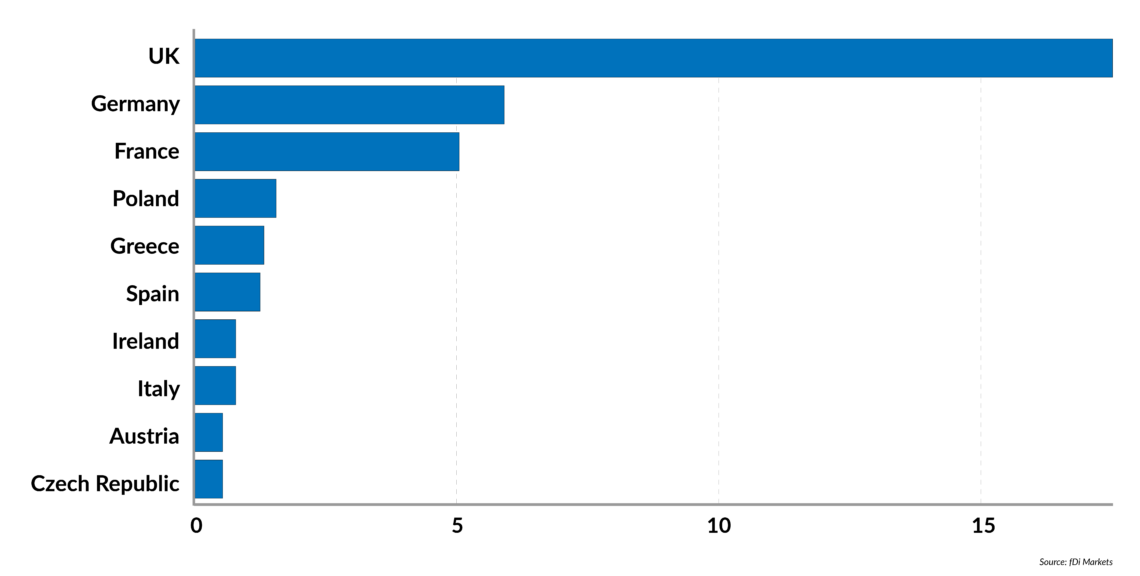

Chinese greenfield investments in the EU

(2009-2018, billion USD)

In April, the EU introduced a new centralized screening mechanism for Chinese and other foreign investments in strategic sectors. The measure, adopted after just 18 months of discussion and planning, calls for FDI to be monitored and reported by EU member states. However, only 14 countries of the EU-28 have the necessary domestic oversight system or concrete plans to introduce one. Italy recently refrained from voting on the mechanism as part of its Italy-first and anti-Europe agenda. According to EU analyses, the new mechanism would have identified 92 percent of Chinese direct investments in Europe last year.

Despite such delays, even partial screening of Chinese investments will over time raise public awareness of the potential security risks and economic dependencies they may create. It will also strengthen the EU’s negotiating leverage with China and help protect its technological sovereignty in key sectors. But ultimately, screening’s effectiveness will depend on means of enforcement, which are still lacking.

Strategic outlook

The EU has just begun to define a new balance of interests in its China policies based on reciprocal conditions. Over the next few years, the most likely scenario is that the bloc will still struggle to adopt a unified position toward China, but will be forced to do so by its looming challenge, including investment projects linked with the BRI. In contrast to the past, the EU will be increasingly unwilling to underwrite an “unequal partnership” in any of Beijing’s long-term projects, especially those that aim for integration into the global governance system at the expense of European interests.

Of course, not all Chinese investments are “Trojan horses” and many will be welcomed (after careful scrutiny). Bigger EU member states will acknowledge that they cannot block Chinese investments in smaller states in the name of the EU’s overall strategic interests, while at the same time promoting much larger expanded trade and commercial deals for themselves. This kind of hypocrisy would only deepen splits within the EU over Chinese investments and infrastructure projects.

EU states both large and small will increasingly recognize that paying lip service to wider geo-economic or geopolitical interests is not enough. To increase their real bargaining power, it is necessary to speak with a “strong, clear and unified voice” on the global level, as the European Commission’s 2016 outline of a new strategy on China stressed.

The alternative is a marginalization of all EU member states in the global arena, including the most powerful ones such as Germany, France and the UK. Europe would be unable to uphold the rule-based, multilateral international order that has allowed it to prosper over the past 50 years.

Even if the EU maintains its newfound unity and assertiveness toward China, that does not mean Beijing will relinquish its control over BRI projects and open its markets as Brussels hopes. As long as nationalism dominates Chinese domestic politics, Beijing’s economic, trade and foreign policies will remain intertwined. More friction over trade and other issues can be expected, and these conflicts will shape the EU’s future China policy.