The U.S. is subsidizing clean energy. What about the EU?

American efforts to advantage its clean energy sector may sting Europe, but Brussels has few effective options to respond.

In a nutshell

- Europe has chafed at a U.S. energy spending package

- The EU is not the legislation’s main target

- Brussels will likely accept a face-saving agreement

Last August, United States President Joe Biden signed into law a tax-and-spending package to reduce consumer drug prices and inject a wave of subsidies into the clean energy industry. The “Inflation Reduction Act” (IRA) will finance projects over the current decade and relies entirely on higher tax revenues, to the tune of $739 billion.

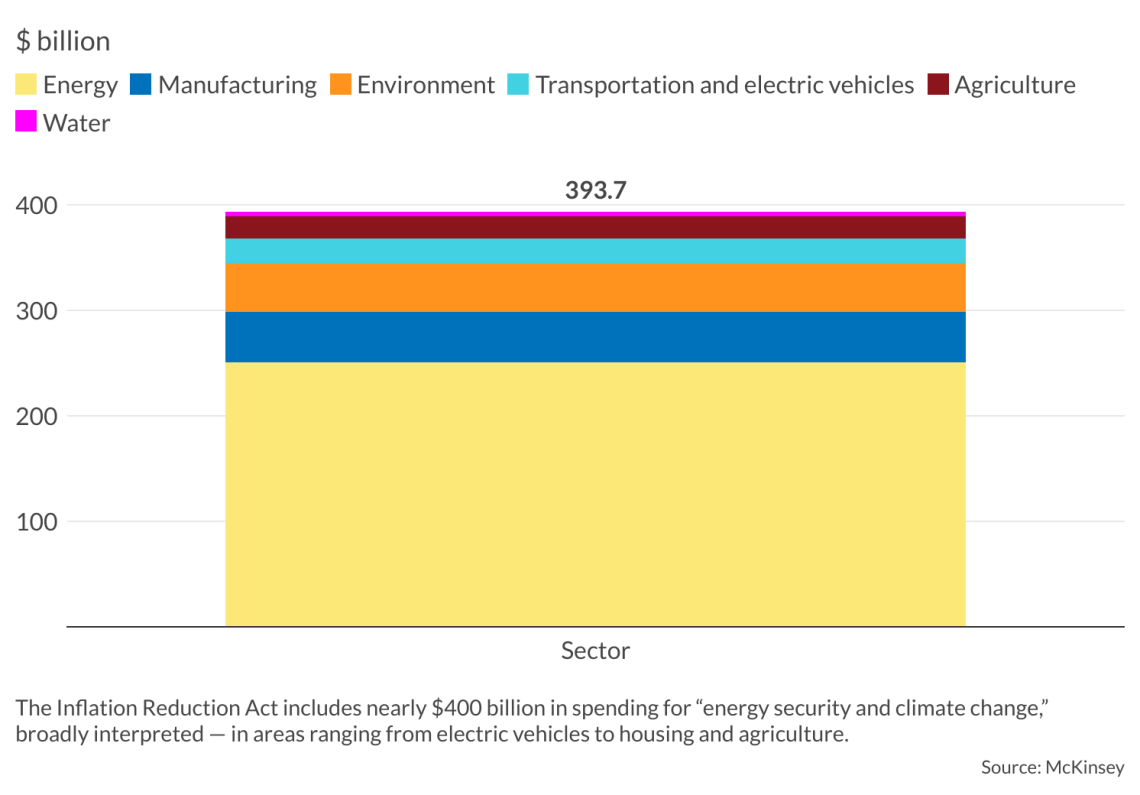

Around $64 billion is allocated to the health sector and $369 billion toward industries involved in “energy security and climate change.” The sector has been defined broadly; for example, although most resources will finance the “energy supply,” billions more will go to housing and agriculture.

The remainder, some $306 billion, is devoted to reducing the budget deficit. Assuming the debt is financed through money printing and, ultimately, inflation, that $306 billion is the supposed contribution to the war on inflation. This sum represents less than 6 percent of the current U.S. monetary base, less than 1 percent of current public debt, and just a fifth of the budget deficit registered in 2022 alone.

Despite the drumbeating, the IRA is hardly shocking in scale, given the size of the American economy. Its main goals appear to have been to persuade the American electorate to support Democratic candidates during the November 2022 elections, and to show that the administration is indeed pressing taxpayers to tame inflation despite rising public spending.

EU backlash

Yet the European Union business community was not overly pleased about the bill and perceived the IRA’s subsidies for the American energy sector as unfair competition. European disappointment intensified when it became clear that part of the IRA would create new barriers to trade flows across the Atlantic. The law introduced significant tax credits for goods with clean-power components manufactured in (and making use of rare earth elements mined in) the U.S. or its free trade partners. As expected, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently confirmed that the administration does not view current trade agreements with China, Japan or the EU as qualifying for the subsidies.

Brussels can only threaten outright protectionism, which would be foolish and counterproductive.

It is unclear whether the IRA’s produce-and-buy-American initiative violates the letter of existing World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements. One can argue, for example, that a qualified tax credit is functionally a nontariff barrier and thus harms foreign exporters. Yet although the IRA surely breaks the spirit of those rules, one cannot help but note that nobody has bothered to involve the WTO. More alarming for the EU is that during the next decade, the clean-power industry will be making massive investments – and that government subsidies will play an important role when companies decide where to locate their production facilities.

Weak hand

Is the EU justified in delivering a “proportional” response, as European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has promised? And would it be worth the effort? In this light, the EU would start a confrontation burdened by three significant disadvantages: the cost of energy, the cost of regulation and the relatively limited funds Brussels can put on the table.

The price of energy in Europe is high and extremely volatile. For example, in January 2014 the cost of natural gas per million British thermal units was $11.59 in Europe and $4.70 in the U.S. The same figure in January 2022 was $28.26 in Europe and $4.33 in the U.S.; in August 2022, $70.04 and $8.79, respectively. In brief, the question is not why energy-intensive companies feel tempted to move away from Europe but where they will relocate.

EU regulation is also heavy and somewhat unpredictable. Certainly, the American bureaucratic machinery is far from light, but a large corporation arguably finds it easier to navigate a policymaking system dominated by two homogenous, disciplined parties and a single federal government, as opposed to a decision-making process involving numerous local power centers (the EU member states), each of them with fragmented internal politics and diversified interests.

It is no wonder that long-term EU planning has become a dubious exercise. Finally, the resources that the EU can deploy (or threaten to deploy) in an arms race of clean-energy subsidies are no match for the American arsenal. Taxation in EU member countries is already high, and Brussels has a tiny budget compared to that of Washington. In 2021, the total EU budget consisted of 165 billion euros – half of what the U.S. Congress will hand out to the renewable energy industry under the IRA and less than 2.5 percent of the entire federal budget.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

What are Brussels’ options, and what scenarios are likely? Three factors stand out. Although the latest U.S. move is relatively modest, it is consistent with the current global trend that rejects free-market principles in favor of an ever-increasing role of government in the economy. Americans and Europeans may differ on the place of regulation versus spending, but they display similar hostility toward private property, freedom of contract and entrepreneurship. Tensions are unlikely to be defused by appealing to free-market principles, and the EU will not soon go down that road.

Second, some commentators have correctly pointed out that the primary goal of the IRA is not to neutralize European competition or attract new investments from abroad. Instead, it seeks to make the U.S. independent of Chinese technology and of some raw materials that the American domestic mining industry has neglected. From that perspective, the law aims at encouraging the domestic mineral industry to develop the resources that America needs at home. There is little Europe can do about that.

Third, Europe surely realizes that it is frequently ignored when Washington, its leading partner, engages in policymaking that affects both sides of the Atlantic. Brussels is a leader in vexing large corporations, but intensifying these efforts – and targeting U.S. companies in particular – will not bear the desired results.

Ultimately, the U.S. and the EU are likely to solve the tensions created by the IRA through bilateral negotiations to fine-tune the meaning of a free trade agreement. Such talks may also bring about a new treaty that will keep China out and offer the EU a face-saving choice: either some European companies will eventually be able to qualify for the IRA subsidies or Brussels will get the green light to launch some new regulatory package with limited funding, with Washington perhaps complaining but not retaliating.

The European choice depends on the extent to which the Commission recognizes its weaknesses and on which terms Brussels manages to coordinate with and garner support from Berlin and Paris. Of course, the Europeans can also decline to choose, simply waiting for – and eventually accepting – a face-saving proposal from the other side of the pond. Indeed, this could be the most likely scenario. Washington has struck at the right moment: Europe features inner economic and political tensions (immigration, the war in Ukraine, poor economic performance in some key countries), a lack of leadership and severe budgetary problems. Besides, American business and Washington’s concern for security have little to fear from Europe and its industrial strategies.

The American clean-energy package is not going to change the long-term dynamic that, when given a chance, large corporations prefer not to invest in Europe and are happy to relocate elsewhere. The only incentive for these companies to stay or develop in the EU is legislation that makes the Old Continent difficult to reach for global exporters.

That explains why the European answer to the IRA will be modest: Brussels can only threaten outright protectionism, which would be foolish and counterproductive. It will likely settle on some modestly financed program to secure consensus from European “champions,” who will thankfully pocket the money and keep investing abroad.