Climate barriers to global trade

Restricting trade for the sake of fighting climate change risks having the opposite effect.

In a nutshell

- Many countries are considering restricting trade out of climate concerns

- The UN and the World Trade Organization are facilitating these policies

- Such trade barriers would have far-ranging adverse consequences

At this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference, some 10,000 policymakers met to continue knitting the global web of climate regulation. An additional 20,000 people were attending as observers, mostly from nongovernmental organizations. More and more, global trade is becoming the focus of their regulatory hankering.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is a treaty with 198 signatory parties. Some of the UNFCCC’s provisions have a clearly defined scope. One example is the Kyoto Protocol, which intends to curb the emission of greenhouse gasses in developed economies. Other clauses have a much broader range, for example, the Paris Agreement. The agreement is meant to coordinate global action to fight climate change. While primarily addressing national governments, the treaty also involves international and nongovernmental actors.

There is no doubt that climate concerns will lead to restrictions on trade. The question is how and when.

In principle, the Paris Agreement does not address the issue of trade specifically. But more and more, the worldwide exchange of goods and services is becoming an object of discussion under the agreement.

For example, the UNFCCC has facilitated discussions about the environmental effects of global trade. Also, its secretariat regularly liaises about this topic with UN agencies, such as UNIDO (industrial development), UNCTAD (trade and development) or the UN Economics Commissions. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) especially has put trade on its agenda. While its mission is to carry out research, its reports have political and regulatory consequences.

Imported emissions

So far, under the UNFCCC, greenhouse gas emissions are measured where they are produced. If a car manufacturer emits five tons of carbon dioxide in Brazil, this quantity is added to Brazil’s inventory.

Another way to measure greenhouse gasses is by consumption – tracking where goods and services reach their end user. According to this method, if a car producer in Brazil sells cars that emit three tons of CO2 in Brazil and two tons in Argentina, three tons should be added to Brazil’s inventories and two to Argentina’s. With this method, the netting of production and consumption leads to Brazil having 2 tons less and Argentina 2 tons more of “imported emissions.”

This second method is not yet applied by the UNFCCC, but the IPCC is researching its implementation. Additionally, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has included it in papers and databases.

Facts & figures

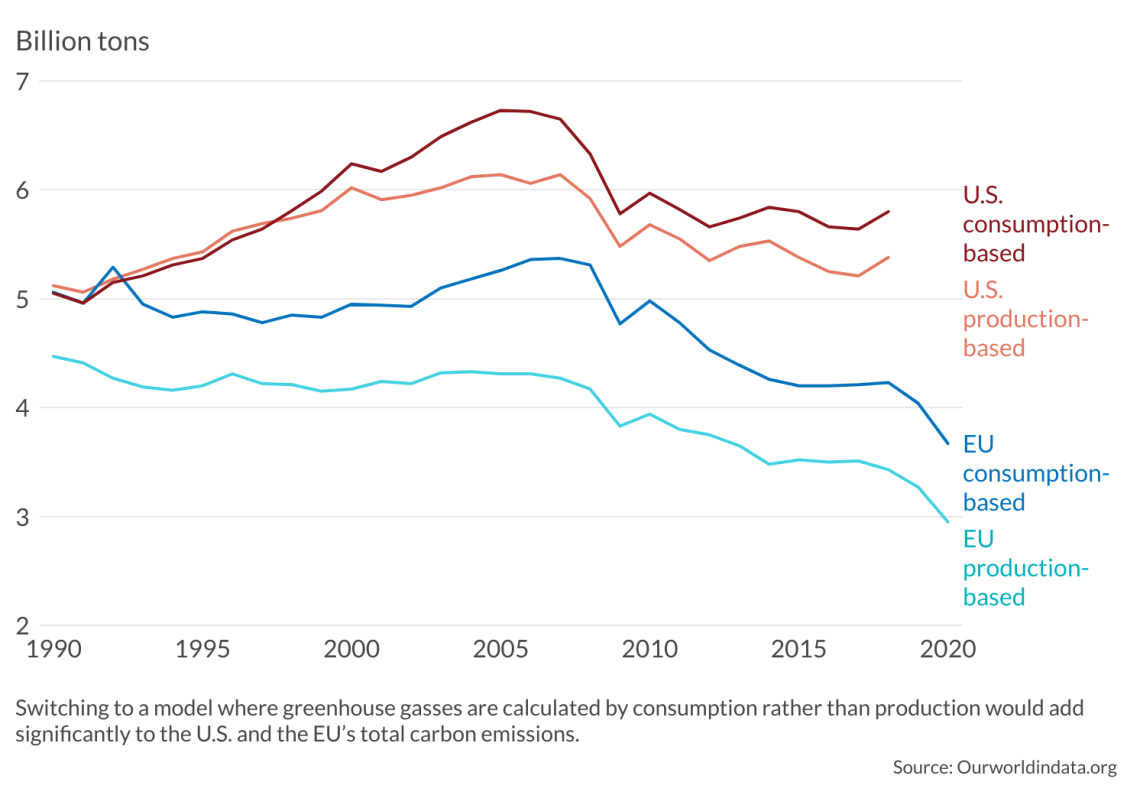

The consequences of calculating emissions by consumption rather than production would be far-reaching. It would add significantly to the inventories of OECD countries, which could come under increased pressure to take drastic action to lower their emissions. This, in turn, is problematic.

If emissions are calculated by consumption, net exporters of greenhouse gasses will be allowed to subtract emissions from their own inventories. With this method, exporting countries would be less incentivized to reduce their carbon footprint. Furthermore, mitigating emissions at the production level is generally much cheaper and improves existing infrastructure and economic processes.

Restricting trade

It can be argued that since the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement are still sticking to the production method of calculating emissions, there is no need to worry. This is wrong on two accounts. First, some parties to the Paris Agreement are beginning to put barriers to trade based on the consumption principle. Second, even the World Trade Organization (WTO) is considering trade restrictions based on the consumption of greenhouse gasses.

Carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAM) are an emerging set of trade policy tools that aim to prevent carbon-intensive economic activity from being imported from jurisdictions with less stringent regulations. Border adjustments would typically apply fees on imported goods based on the greenhouse gas emissions generated during their production abroad. This can also include deductions or exemptions from domestic policies for producers that export their goods.

More on climate change:

The next wave of mass migration

The EU’s endemic migration crisis

The European Union is currently considering implementing CBAM. Interest in border adjustments, including carbon tariffs, is also growing in the United States, with both Democrats and Republicans expressing support.

Since CBAM are taxes that apply to imports, the measures would need to comply with WTO rules. A CBAM can be WTO-compatible if it avoids discriminating among foreign products with the same carbon footprint and treats all domestic production with the same tax. The wording, goals and application of border carbon adjustments should be entirely origin neutral.

The WTO itself is seriously considering such steps. In its briefs on trade and climate change, the organization praises the growing number of climate-related national policies as well as the increase of climate provisions in free trade and regional trade agreements. While it notes how trade can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, it also states that climate-related barriers to trade are compatible with WTO rules if a common standard for accounting emissions is established. The WTO effectively lays out the blueprint for restricting trade. Under the UNFCCC, the standardization of carbon accounting is well underway.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is that global trade will be restricted based on climate change concerns. Regardless of whether this stems from legitimate reasons or serves to justify protectionism, the economic consequences will be dire. Less trade means more expensive goods in importing countries as well as fewer proceeds from trade in exporting ones, leading to a welfare loss. There will be less technology exchange, less competition, economic and social development, and potentially less climate action to mitigate emissions.

Another possible scenario is a global divide. The EU, and potentially the U.S. and Canada, will adopt new trade restrictions while most other countries will not. This could propel the economic decline of the transatlantic protectionists while allowing for countries such as China, Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia and South Africa to integrate more into global trade networks. This would also boost their geopolitical influence.

Yet another scenario is one in which trade fragments. In this scenario, international ties would fray, subsisting only among like-minded countries, resulting in isolationism and geopolitical frictions leading to global economic decline. Such an outcome would take a disproportionate toll on the poorest.

These scenarios are all variations of a bad situation. There is little probability of a best-case scenario in which trade is seen as a tool to mitigate the effects of climate change. There is no political appetite for such an approach since even self-styled advocates of a liberal order, such as the OECD or the WTO, are considering barriers to trade. Even a neutral scenario, in which climate action does not infringe on trade, is highly unlikely if the EU adopts CBAM. There is, however, some optimism about the timeline, as restrictions may take a long while until implemented.

There is no doubt that climate concerns will lead to restrictions on trade. The question is how and when. The EU’s CBAM provide a blueprint for a regional set of barriers to foreign trade. The WTO’s condition of a worldwide tariff system on standardized carbon accounting is another cornerstone in this development.

Such restrictions will have a negative impact on the economy, social development, welfare and even geopolitics. They are also highly likely to interfere with efforts to combat climate change, especially the reduction of carbon emissions.