Paying the sustainability bill with inflation

The war on climate change will soon return to center stage, with grand policy designs to be financed by inflation.

In a nutshell

- Climate change will soon recapture the global spotlight

- Lawmakers will step up regulation and centralization

- Ambitious, expensive policies will be financed by inflation

The end of 2022 was characterized by relatively good news. The Covid-19 pandemic is no longer a global threat; supply bottlenecks are easing and central banks appear to be bringing inflationary pressures under control.

Of course, growth remains a major concern. Yet, Western leaders do not seem overly concerned about it. After all, they have a narrative to recite: a recession is indeed unavoidable, but policymakers are keeping it in check and should be praised for having upheld social justice in hard times, made unstable economies more resilient and averted systemic crises with centralization and regulation.

The major perceived challenge remains public finance, especially in the United States and in Europe, where most countries have a debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio well above 60 percent, the threshold that most economists used to consider dangerous to cross. By the end of 2022, the ratio is expected to reach 138 percent in the U.S. and about 94 percent in the euro area. However, officials do not seem overly concerned. Some even do not believe that public finance is a significant issue as long as friendly central banks can come to the rescue, buy treasuries and keep real interest rates negative.

Lawmakers are now persuaded that the limits to public debt are less stringent than previously thought, and that grand policy designs can be realized even without satisfactory growth. Though future negative shocks cannot be ruled out, both national and supranational policymakers act as if such shocks affect only the timing of their projects, not their content.

Grand designs

In this light, the war on climate change and the transition to ecological sustainability will surely return to center stage – growing in prominence as soon as central bankers again feel free to engage in new waves of generous monetary policy.

COP27, the November 2022 United Nations climate change conference held in Egypt, was the first sign of this global reversion to “grand design” thinking. Poorly prepared, it turned out to be a failure. Participants did agree on the need to contain global warming, reiterating a lofty pledge to limit any temperature rise to 1.5 degrees above preindustrial levels.

But they went no further than vague declarations to act and failed to agree on any common strategy or clear timeline.

Developing countries did take the opportunity to pressure richer participants into financing a “loss and damage” fund, meant to help them adapt to and mitigate the damages caused by climate change. In general, however, COP27 confirmed that the future of climate policy will be characterized by efforts to intensify regulation and centralization and to build the necessary consensus.

Big ideas

To understand what that not-too-distant future might look like, we may reconsider what happened to sustainability – the global project that preceded the climate change saga.

According to the UN’s Brundtland Report, a key 1987 document, sustainability means meeting “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Such an objective appears worthy enough, so much so that the UN has developed it into 17 “goals” and 169 “targets.” Yet, this very definition of sustainability in fact has little operational content. What exactly are the needs of present and future generations? Are all members of present and future generations entitled to the same needs, as defined by today’s national or global regulators?

Facts & figures

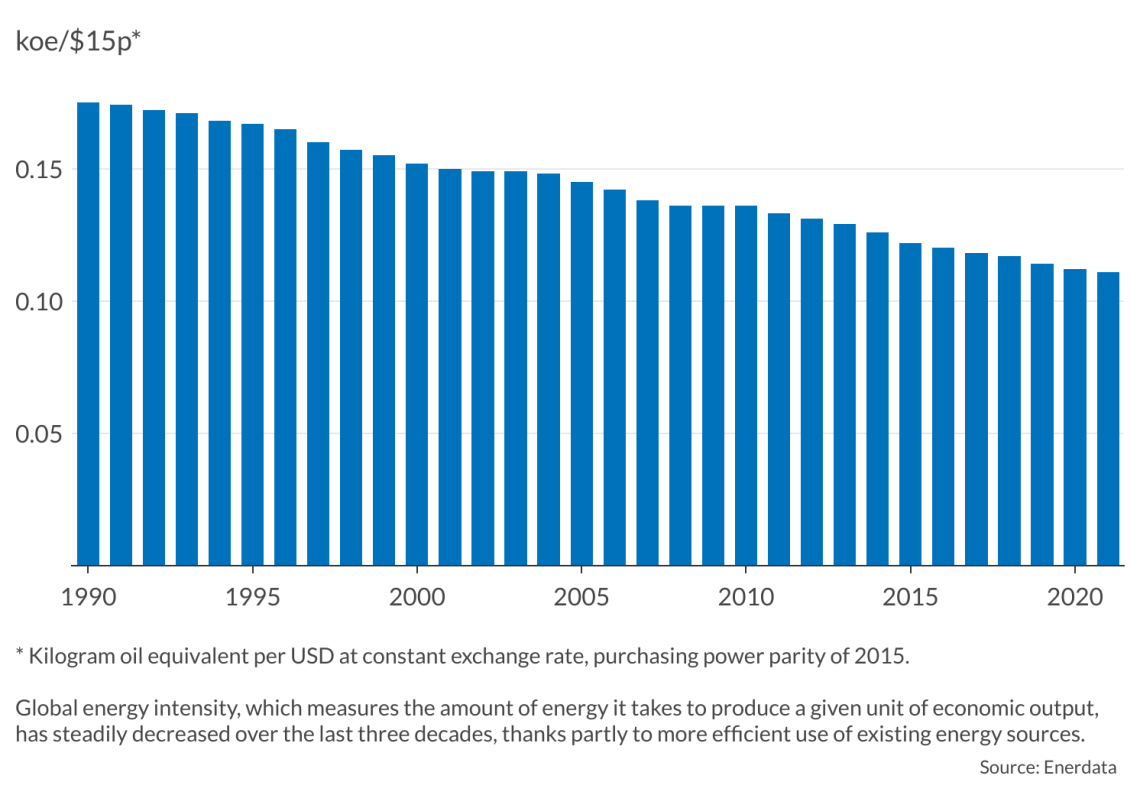

Moreover, since the notion of sustainability regards the exploitation of inputs, one may doubt that regulators know which inputs will be available in the future or how technologies will evolve. For example, did UN experts anticipate that over the past 30 years, proven oil reserves would grow by 70 percent? Similarly, these experts may know that the world’s annual energy needs amount to the power we receive from the sun in 90 minutes. Are they really sure that our descendants will fail to develop technologies able to exploit a tiny fraction of that enormous energy source? Or those that will make more efficient use of the resources already familiar to us? After all, this is what has happened in recent decades, such as with coal, oil and nuclear power.

More generally, we already have a system for signaling when the exploitation of a resource becomes potentially unsustainable, encouraging scientists, engineers and entrepreneurs to look for alternatives. It is called the “price system.” Are we sure that policymakers and regulators can do a better job of monitoring scarcity and encouraging successful innovators?

Central planning

Many observers would answer these questions in the negative. And still, the rhetoric of sustainability is not just a fad – it is a battle cry that will likely justify a vast program designed to control individual consumption and to allocate resources (taxpayer money) to selected industries and companies. Although the public may tolerate controls and regulation for the sake of sustainability, it may well oppose systematic subsidies to the producers eligible for compensation. Under such circumstances, one may expect at least partial nationalization of key sectors.

Of course, sustainability also includes efforts to make the economies more “circular,” promoting a framework that “involves sharing, leasing, reusing, repairing, refurbishing and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible,” as the European Union has put it. Again, such thinking distrusts the price system, overestimates the wisdom of regulators, and ignores the costs of reusing and recycling. To take one example, the failure of sorting and recycling plastics has already become clear. And we do not yet know just how much money has been squandered on similar programs that never had a chance to succeed or that were simply inferior to the alternatives.

Although the public may tolerate regulation for the sake of sustainability, it may well oppose subsidies to compensate producers.

The campaign for sustainability has aimed to design global policies under centralized supervision, with no regard for the price system. When necessary, public debt and taxation were meant to finance its champions and compensate those who would suffer from the consequences. So far, this project has failed to make much progress at a global level, although it has justified plenty of domestic regulation. The basic reason is a lack of international cooperation: an intergovernmental cartel has failed to materialize.

Price tag

For its part, the campaign against climate change has been just as successful in advocating global, centralized decision-making – announcing ambitious targets, and persuading the public that these are exceptional times and that adaptation is not enough. Not unlike the sustainability saga, COP27 has shown that these projects focus on global policy designs, rather than specific, realistic goals.

The UN summit, however, emphasized two elements that were not always evident in the debate over sustainability, and which help explain its partial failure. First, keeping the policy dream alive requires a global consensus – and that does not come free. This time, Western officials got the message, and acceded to handing out funds to those countries who threaten to walk out of the room and torpedo the entire project.

The second element regards the origin of this generosity. In the past, fundraising by government authorities was at least partially constrained by concerns of public finance. This may no longer be the case in the future, especially if people get used to living with moderate inflation and creditors accept negative real rates of interest on assets issued or guaranteed by governments and international organizations.

If this reading is correct, one should expect that future grand policies in the realm of climate change and sustainability will be financed by inflation. Western regulators and many third-world rulers will profit, and far too many people will believe they are enjoying a free lunch.