The EU’s new plan to address irregular migration

Implementation of the European Union’s new Asylum and Migration Pact still requires difficult political compromises on national and EU levels. June elections to the European Parliament will determine what is achievable.

In a nutshell

- Europe is taking a pragmatic approach to migration and relations with Africa

- The EU’s asylum pact aims for more efficient migration processes

- Irregular migration to Europe is on the rise with no end in sight

Migration – and the political challenges it creates – is a key agenda issue ahead of June elections to the European Parliament. After the surge in irregular migrants to Europe in 2015, terrorist attacks the following year and the European Union cobbling together initial rules to control immigration, disagreements prevailed.

In 2020 Brussels put forward a new plan. After significant negotiations, in December 2023 the EU’s parliament and member states agreed on the Asylum and Migration Pact – now the bloc is working toward implementation. Its initial effects are primarily symbolic; while important politically, full enactment still requires difficult political compromises on national and EU levels.

Understanding migration to Europe

Irregular migration into Europe is rising. According to the European Union’s border agency, Frontex, there was a significant increase in irregular border crossings in 2023, estimated at approximately 380,000 people, driven by economic, social and security instability in some parts of Africa. Over the last 15 years, Frontex has detected 1.4 million irregular border crossings of African nationals.

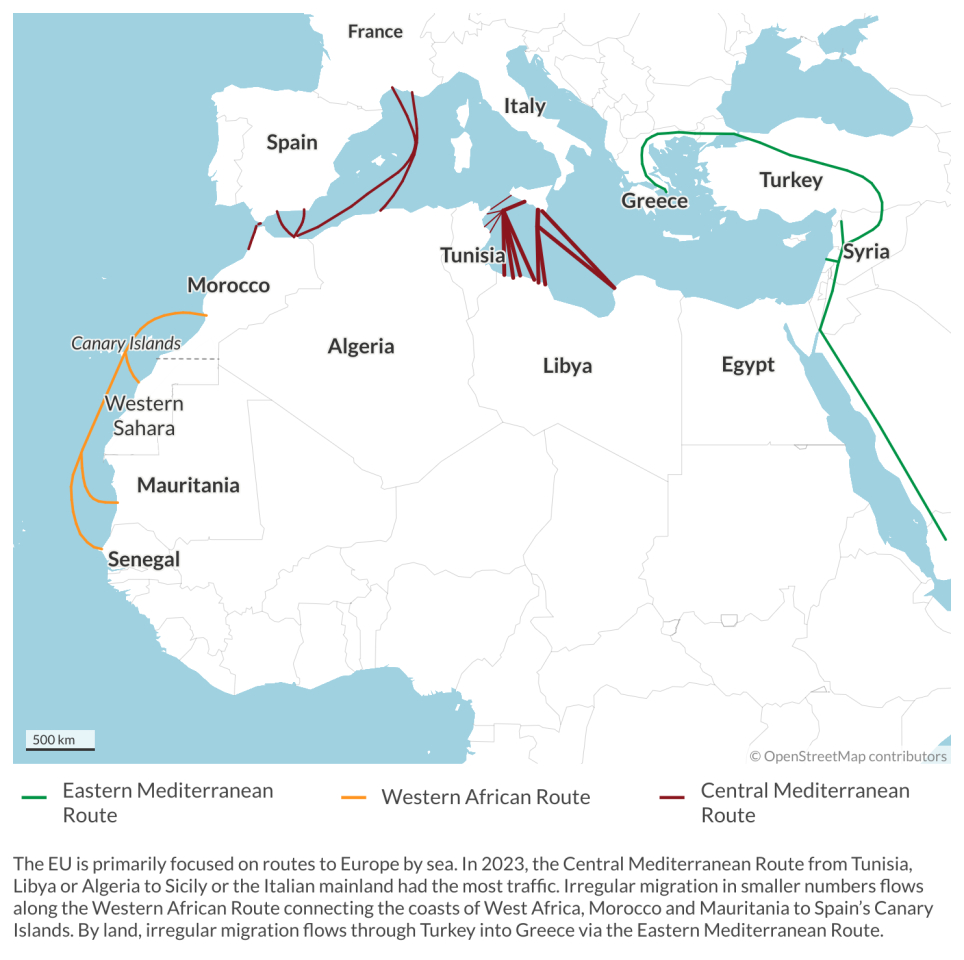

The main routes were through West Africa and the eastern and central Mediterranean. The most active migratory approach (accounting for 41 percent of irregular crossings) was the Central Mediterranean Route, with African migrants accounting for almost half (47 percent) of all recorded migrants. While smaller in number, irregular migration flows along the Western African Route doubled in 2023 to reach their highest rate since 2009.

As GIS has previously noted, the factors causing African migration to Europe will persist. Africa has the lowest average per capita income in the world. At the same time, deterioration of the continent’s security landscape – as evidenced by war in Sudan, ongoing tensions in the DRC or persisting patterns of violence and instability in the Sahel – is increasing displacement and refugee flows. That in turn weighs on the political and economic prospects within Africa. This suggests that migration – both within Africa and from Africa to other regions – will remain a path for Africans to escape threats to life and limb.

The continuous immigration flows are forcing Europeans to agree to new rules on external border management, asylum procedures and data collection.

Changes to EU migration rules

Primary changes introduced by the pact relate to the Asylum Procedure Regulation (APR), which aims to accelerate the processing of asylum claims and to prevent those considered ineligible from entering EU territory in the first place. In 2023 there were more than 1 million asylum claims, the highest number since 2016.

The APR introduces mandatory border procedures for asylum seekers applying at external border crossing points, in connection with illegal border crossings and following disembarkation after search and rescue operations. It applies to those presenting security risks, providing false information or migrants from countries with a personal recognition rate below 20 percent. Recognition rates – the probability of an individual being correctly identified by a system – vary both by EU country and the migrant’s country of origin. Whereas Eritrea, for example, has a high recognition rate, Nigeria has a lower one. One APR support mechanism is the collection of biometric data, which is expected to subsequently include additional data such as facial images.

Margaritis Schinas, European Commission vice president, compared the agreement to a house with three floors: one dedicated to relations with third countries, the second with the management of external borders and the third focused on responsibilities among member states.

Obstacles to consensus

One contentious and unresolved aspect of the pact is the solidarity mechanism. It aims to have member states receive asylum seekers or provide financial contributions to border management at critical moments. This would be applied in circumstances such as a migration crisis at the EU’s external borders or when external actors (non-European countries or non-governmental groups) exacerbate migration flows.

Yet the measure prevents the EU from forming a cohesive bloc. Hungary and Poland (despite changes in government) remain critical of the solidarity mechanism. The Czech Republic was an early proponent, advocating for financial contributions to EU countries taking in migrants, as opposed to redistribution quotas. Yet in February, citing last-minute concessions to the solidarity mechanism agreed in Brussels, Prague said it would withhold support and opt out of its implementation. Citing strife in Sweden as an example, none of these countries is eager to host migrants from North Africa nor the Middle East.

Germany, where 352,000 people sought asylum in 2023, as well as France are changing their migration laws to respond to voters’ concerns.

Read more on migration and its risks for Europe

- Sweden looks into the abyss

- Zero tolerance for terrorism and its supporters

- Asylum seekers versus economic migrants

- Europe’s border agency searches for support

One geopolitically critical aspect of the changing rules is the introduction of the concept of “safe third countries”: non-EU countries through which migrants transit but which are themselves considered safe havens for asylum seekers. Determining which countries meet the requirements, especially in North Africa, and how the EU and safe third countries administer the process in practice, are open questions.

Remittances from Europe

Revenue from migration is another factor worth considering, as remittances – when migrants send money they earn abroad back to individuals in their home country – have become a critical source of income for many nations. In sub-Saharan Africa, remittances reached an estimated total of $54 billion in 2023. In North Africa, they have become the largest source of incoming funds, surpassing foreign direct investment and official development aid. Remittances are crucial to the economies of Morocco, Senegal, Somalia and Gambia, where they account for 8.3, 9.4, 15.1 and 18.4 percent of gross domestic product, respectively. Many African governments will count on this source of revenue going forward.

African cooperation to tackle displacement

Frontex and Senegal have recently launched a plan to tackle irregular migration, with cooperation extending to Mauritania and Gambia. One method aims to prevent migrants from crossing the desert or the Mediterranean by relocating them from coastal cities inland or forcibly deporting them to neighboring countries.

Tunisia signed a deal with the EU worth 1 billion euros, under which financial support will follow an agreement with the International Monetary Fund in exchange for Tunis’s commitment to curbing illegal migration. The country became the primary departure point for migrants trying to reach Europe after the fall of Muammar Qaddafi in Libya. But while talks on migration continue, tensions between President Kais Saied – who is becoming increasingly autocratic – and the EU have been rising.

Facts & figures

Because their cooperation is necessary for Europe’s quest to curb migration, these countries enjoy increasing leverage in talks with the EU (and some individual European countries) and can force geopolitical concessions.

This complex relationship is visible in the case of Morocco, an origin, transit and destination country for African migrants. Moroccan authorities intercepted an estimated 87,000 illegal migrants in 2023. In 2021 amid a diplomatic spat with Spain, Rabat temporarily suspended migration surveillance along the border with Ceuta – a Spanish enclave on the North African coast bordering Morocco – leading to a chaotic situation. In the span of just a few days, roughly 8,000 undocumented migrants, including 1,500 minors, rushed into the enclave by swimming or climbing over fences. The episode marked a turning point in the kingdom’s relations with Spain, and forced Madrid to recognize Morocco’s position on the Western Sahara dispute, namely that the Western Sahara should be considered Moroccan territory.

The EU’s increasingly transactional approach also increases its exposure to side effects of political turmoil in third countries.

The EU itself reached an agreement with Morocco on migration in December 2023, and appears open to Morocco’s claims to Western Sahara. Yet the General Court of the European Union has, until now, blocked formal recognition. A European shift toward such recognition would come with additional strategic risks, such as compromised relations between the EU and Algeria, which, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, became the third-largest supplier of natural gas to Europe. In opposition to Morocco’s claims to Western Sahara, Algeria supports the Polisario Front, a Sahrawi nationalist liberation movement claiming the region as its own.

The EU’s increasingly transactional approach also increases its exposure to side effects of political turmoil in third countries. In Niger, for example, the junta that came to power after the July 2023 coup revoked a 2015 law that criminalized the transport of illegal migrants across the desert. The decision came after the EU suspended financial support to Niger.

EU member states’ migration solutions

Being heavily exposed to migration, Italy stands out as an important example of managing European solutions in lockstep with its own national strategy. Having presented migration control as a key electoral pledge, the government of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni is actively supporting the EU pact while simultaneously leading a nationally-oriented approach, called the Mattei Plan. This plan offers Italian investments in energy, infrastructure and development aid to African states willing to cooperate with Italy on migration.

Focusing on North Africa and aiming to start with projects in nine countries, the Mattei Plan provides an initial commitment of 5.5 billion euros to support the economic development of origin and transit countries (more on this in an upcoming GIS report). From a geopolitical perspective, it may bear fruit. Prime Minister Meloni has recently concluded a new cooperation agreement with Egypt, while courting other potential partners in Africa, such as Niger, where authorities have expressed their desire to work with Italy. Italy’s ever-closer ties with countries in North Africa and the Sahel contrast with the deterioration of relations between these countries and France.

Greece – where migration was a decisive issue in the last elections – is also adopting more surgical measures to curb illegal migration while responding to its own economic needs, by enhancing bilateral cooperation with Egypt and opening legal pathways for Egyptian seasonal farm workers.

Scenarios

It will take at least two years for the EU pact to be implemented. However, the announcement of the agreement confirms that Europe is now taking a more pragmatic approach to migration, and to relations with Africa. The bloc recognizes that migration patterns will be determined by a combination of factors, many of which are beyond European control.

Most likely: Instability ensures continued migration

Increasing migratory pressure will continue, driven by rural-urban migration in Africa and by the deterioration of the political and security outlook in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and, possibly, West Africa. The war in Sudan, for example, triggered 6 million cross-border displacements in 2023.

Risks on the eastern route, connecting the Horn of Africa to the Gulf states through Yemen, will also add pressure and lead to an accelerated buildup of security measures along the EU’s external borders.

African countries along migration routes will maintain, and likely increase, their leverage over the EU, especially as regards EU states more exposed to irregular migration, like Spain or Italy. In this context, Europe will remain vulnerable to the weaponization of migration and migration crises – a possibility noted in the pact – triggered by economic collapse or civil unrest (in Tunisia, for example), or by tensions over the Western Sahara (between Algeria and Morocco or between Morocco and the EU).

A scenario of crisis in a time marked by political shifts could lead to the implementation of border controls within the Schengen area (as some countries are already doing), limiting the free movement of people.

Less likely: New EU-African initiatives swiftly bear fruit

Under a less likely scenario, efforts by the EU and by individual member states, combined with higher mobility within Africa, result in better management of migration. This scenario is less likely because higher mobility and gainful employment within Africa are predicated on economic opportunities being present in the near term.

Even under a best-case scenario of enhanced mobility and economic opportunities, migration will remain a necessary way for many people in origin countries to seek improved economic prospects or escape political persecution. At the same time, there is a growing perception among European voters that current levels of migration are compromising the bloc’s social cohesion.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.