The economics of a trade crisis

Financial markets were not happy that the U.S. and China failed to sign a long-overdue trade agreement. The world of business believes that the crisis is not temporary but that its consequences are far from dramatic. Thus, the dip in stock prices is just a healthy correction after the recent fat gains. There are, however, less rosy scenarios, too.

In a nutshell

- The markets may be right in assuming that the U.S.-China trade crisis is only temporary

- They may also be right in assuming that the crisis’ impact on global commerce will remain limited

- If these assumptions are wrong, however, the resultant uncertainty could hurt global business

The trade dispute between the United States and China has become a never-ending story. In April, the final agreement was about to be signed. It seems that at the eleventh hour, the Chinese showed up with new proposals, which the Americans considered a regress compared to what had been established, and therefore unacceptable. A new broadside of tariffs and counter-tariffs followed. What will come next? And what consequences can we expect for the world economy?

In truth, financial markets did not seem frightened by the recent setback. Stock markets retreated from their recent highs, but only by a few percentage points. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, for example, is still 10 percent above its early January levels, while German and Chinese stocks are about 15 percent higher than in early January.

Three explanations

In this context, three options are worth exploring. Either the markets are right because the crisis is only temporary, or they are right because this crisis is less important than the media presume. Alternatively, the markets are wrong and sooner or later, investors will have to reassess their expectations. Let us consider these three scenarios in turn.

The Chinese president probably needs to demonstrate at home that Washington has not bullied him.

A scenario in which the current trade crisis is only a temporary flare-up rests on two assumptions. First, the two leading players – Chinese President Xi Jinping and U.S. President Donald Trump – are powerful and charismatic individuals rather than bureaucratic figures. This has consequences. Bureaucrats move slowly and do not care much about popularity, image, clienteles or electoral success. In a word, they are predictable. High-profile actors are different. President Trump insists on showing his leadership, but he must also produce results, especially if the American economy slows down before the next elections take place. The Chinese president, for his part, probably needs to demonstrate that Washington has not bullied him and that benefits in other areas are compensating his eventual concessions on the trade front.

According to this scenario, the Americans will insist on forcing the Chinese to come closer to the free-trade vision. However, President Trump will probably be ready to relent in other areas and thus allow the Chinese to revise the draft of the trade deal that was about to be signed at the end of April. The big question, of course, regards the content of these “other areas” that would be included in a new, comprehensive agreement.

One delicate issue is communications technology. For example, the Chinese might be willing to go back to the previous draft of the deal if the Americans opened their high-tech communication market to the Chinese. Will this happen? Maybe it will, especially if the Americans realize and admit that the Chinese could be leading the industry before long. Put differently, many observers assume that the new technological standards will come from American giants such as Google, Apple or Microsoft. What would happen if they came from the other side of the Pacific Ocean before long? Would the Americans force the rest of the world to boycott Chinese technology? Or would they try to cooperate and compete?

Preferred outcome

If investors believe that the second strategy is more realistic and that it will soon come true, then they will likely put their money on a relatively quick settlement of the current trade disputes. Of course, this would be the preferred outcome from the outside world’s viewpoint. Cooperation between the U.S. and China would mean tolerance, rather than kissing and hugging. Tolerance necessarily implies simmering tensions, but cutthroat competition and unfettered free trade would unleash economic growth and ensure geopolitical stability for years to come.

Facts & figures

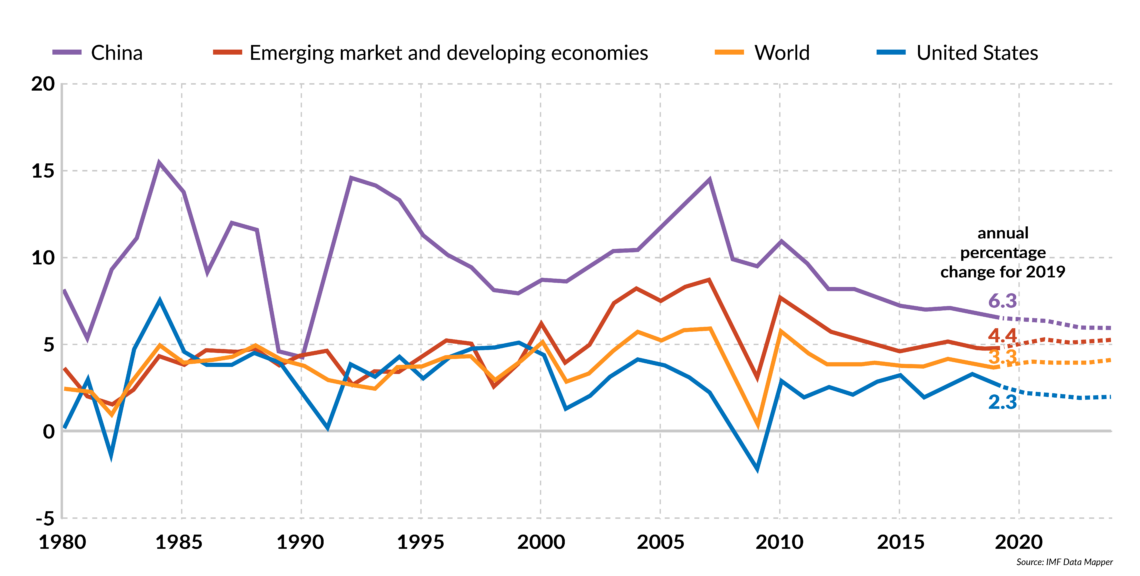

Real GDP growth, annual percentage change

The second scenario would take into account what has transpired since the beginning of the trade war in early 2017 and draw conclusions. Briefly put, the data show that in 2018, world growth was relatively satisfactory at 3.6 percent in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), as measured by the International Monetary Fund. It was 3.8 percent in 2017, and the prospects for the current 2019 remain good (a 3.3 percent uptick). In other words, although tensions have been a burden, their impact has not been and will not be catastrophic. In particular, the U.S. economy is doing well, and the same is true for China, where the slowdown in GDP growth continues to be milder than commentators have been predicting for the past decade.

Parts of Western Europe, Russia and parts of Asia may become coveted markets for China and the U.S.

If China and the U.S. keep doing well, and the rest of the world is allowed to carry out business as usual with these two superpowers, why should one worry? Moreover – one may argue – weaker trade flows between the U.S. and China imply more opportunities for those producers who can exploit unmet demands for foreign goods in the two countries. Of course, the underlying assumption characterizing this scenario is that it cannot get any worse and the rest of the world can keep producing and trading regardless of the trade relations between the two superpowers, with nobody forced to take sides.

In particular, if all this were true, ongoing tensions between Beijing and Washington could offer unexpected chances to some lagging and undeveloped economies. Parts of Western Europe, Russia and parts of Asia would become coveted markets for China and the U.S. Their players would be looking for buyers, suppliers and possible recipients of foreign direct investments.

The uncertainty factor

The third scenario is a gloomy one: it refers to a situation in which the bilateral trade war does not remain isolated and threatens competition and cooperation worldwide. Although we believe that the dangers in this direction are overstated, the real threat comes from uncertainty. Most companies might not care much about what happens in Beijing and Washington. But large corporations usually do care, and refrain from engaging in major investment programs until the picture clears up, and the network of geopolitical relations stabilizes. This does not mean that investors duck their head until everything is quiet. Investors are likely to stay put until they believe they know of the intensity and geographic extent within which tensions will be mastered and contained.

Although nobody feels the need for a new international order, capitalists want to know how much disorder they can expect and play defense when they are facing an overly blurred picture. In our view, this is what is happening now. The plans for expansion overseas – in Asia and in North America – have been shelved, at least for a few months. Global competition will still be relentless and the race to meet buyers’ needs will continue to create winners and losers, depending on the companies’ past investments and their exposure in sensitive markets. However, the competition will fail to encourage companies – winners and losers – to do what it takes to win the next rounds. This attitude is slowly being captured by stock prices, which could drop further until the clouds dissolve, at least partially.

To conclude, we are inclined to believe that the world can easily survive a trade war between China and the U.S. Surely, consumers and selected producers will pay the price on both sides of the Pacific Ocean. One should not overlook that the main advantages of free trade lie in the competitive pressures that go with it. These pressures will not weaken just because some 15 percent of world commercial flows has become the hostage of a trade war. However, they could weaken because global business is unwilling to take chances. In this light, one may argue that this crisis has revealed the lack of vigor of today’s entrepreneurs. Or, perhaps, that excessive taxation and regulation have reduced net expected profits and, thus, the willingness to take chances. Most likely, both phenomena play a role and, in the future, even relatively minor ripples might appear as daunting obstacles.