The oil-market crunch

The Covid-triggered collapse of global demand for oil has produced the worst disruption in the industry’s history. Output reductions agreed upon by OPEC and other major actors have made little difference, as much of the world’s economic activity was frozen by governments.

In a nutshell

- The oil industry is going through its worst contraction ever

- As oil demand remains at historic lows, OPEC is powerless

- The industry cannot cut its output enough to raise oil prices

This report is part of a GIS series on the consequences of the COVID-19 coronavirus crisis. It looks beyond the short-term impact of the pandemic, instead examining the strategic geopolitical and economic effects that will inevitably be felt further in the future.

This will be a watershed year in the history of oil markets. Since 2020 began, several unprecedented developments have taken place, from an unparalleled decline in global demand, to negative prices for the first time, to record production cuts aiming to salvage revenues and the closest cooperation among oil producers the industry has ever seen. The governments aim “to use all available policy tools to … maintain market stability,” the G20 said in its April Energy Ministers Meeting Statement.

Facts & figures

Oil industry in the times of crisis

- On Monday April 20, 2020, the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) turned negative for the first time in the history of the oil industry

- The Chinese economy, the world’s second-largest after the U.S., shrank by 6.8% in the first quarter of 2020, marking the country’s worst performance for decades

- OPEC+ was formed in December 2016 and agreed on a cumulative cut of 1.8 mb/d (1.2 mb/d from OPEC and 600,000 b/d from non-OPEC group of producers led by Russia), effective as of January 2017 and set for six months

- Between January 2017 and January 2020, OPEC’s global oil market share shrank from 55.6% to 49.2%

- The NOPEC bill was first introduced in the U.S. Congress in 2000 and was voted on several times since, but never passed

- Prior to the coronavirus crisis, most organizations expected a global economic growth of around 3% for 2020

- Russia has a budget break-even price of $42 per barrel.

‘Crisis like no other’

As of late April, the negative price phenomenon has occurred only in the United States and affects one crude oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI). Other important crude markers, such as Brent, remain in positive price territory. Records show that natural gas prices turned negative on several occasions over the last few years in the U.S. because of oversupply and infrastructure bottlenecks. Also, in the early days of the American oil industry, oversupply caused some oil to be wasted. (No environmental regulations or future contracts existed then; if they had, prices might have turned negative.) The waste led the Railroad Commission of Texas to introduce production quotas long before OPEC came into existence in 1960.

Today, oil market drivers are much bigger than the sector itself. There is no guarantee that any government action can deliver market stability. Powerful outside forces will likely dictate the markets’ shape throughout most of the year, perhaps even into 2021. To slow the spread of COVID-19, countries around the world imposed strict lockdowns, which have hit the global economy hard and, subsequently, reduced oil demand. How the world will recover from a “crisis like no other,” to quote the International Monetary Fund (IMF), will depend on a wide range of uncertain factors. This unpredictability has resulted in a spectrum of forecasts – which, in turn, lead to several scenarios for oil markets.

Low oil prices will support an eventual economic recovery.

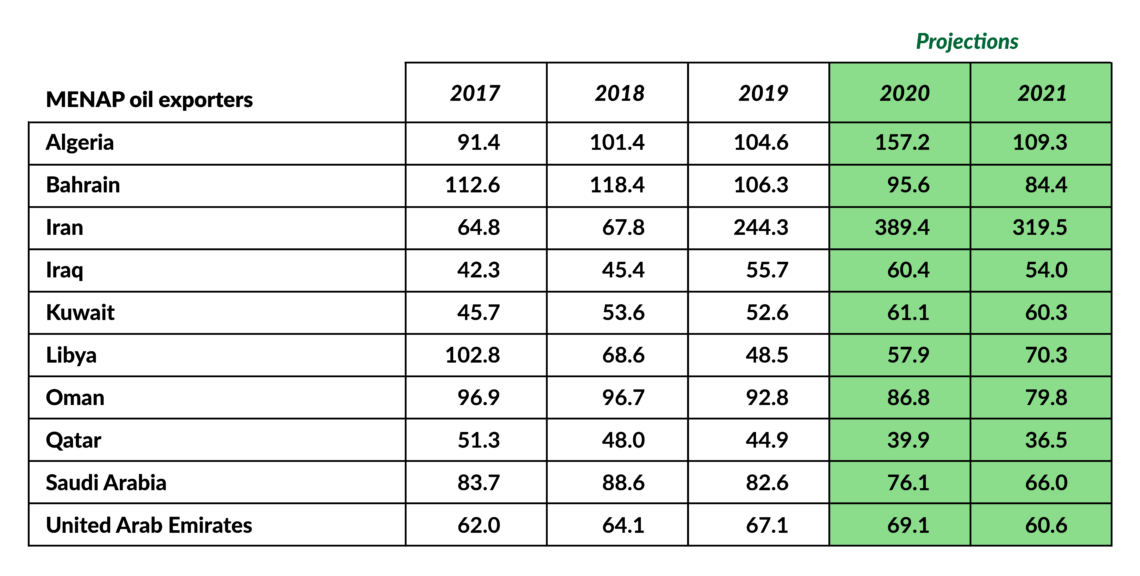

If history is any guide, it may take a long time for oil prices to regain their pre-pandemic levels. That prospect is most alarming for oil-producing countries, particularly those where economic diversification has made little headway and governments are most dependent on income from the energy sector.

The rock-bottom oil prices, however, are not uniformly disastrous. On one hand, they may not boost oil demand during the lockdown, which cripples the transport sector, a leading user of oil. On the other hand, low oil prices will support an eventual economic recovery. Depressed oil revenues also provide a powerful incentive for many governments to start pursuing long-delayed economic reforms.

Miscalculations

At the start of 2020, oil market discussions were focused on one central issue: geopolitical risks. Following the United States’ January 3 attack that killed Iranian General Qassem Soleimani, experts rushed to analyze its impact on oil markets, with many fearing an Iranian retaliation would cause a spike in prices.

A few weeks later, such fears evaporated as the developing pandemic began to capture the attention of the global community. Until the end of February and early March, however, the prevailing perception was that the coronavirus, like SARS before it, would largely remain confined to Asia. “Within a couple days [it] is going to be down close to zero,” President Trump stated on February 26, referring to the rate of infection in the U.S.

Also in February, BP’s chief financial officer estimated that oil demand would be only 300,000 to 500,000 barrels a day (b/d) weaker this year on the account of the virus. Similarly, in its February Oil Market Report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) expected the demand to fall by 435,000 b/d year-on-year in the first quarter of 2020. The agency also cut its 2020 growth forecast by 365,000 b/d, to 825,000 b/d.

Likewise, in early March, OPEC still expected a demand increase, albeit smaller than its previous forecasts. The organization projected oil-demand growth of 480,000 b/d in 2020, down from 1.1 million barrels per day (mb/d) in December 2019. As a result, on March 5, OPEC reconvened in Vienna and announced additional production cuts of 1.5 mb/d (OPEC 1 mb/d and non-OPEC 500,000 b/d) until the end of 2020. A short while later, all these figures appeared minuscule.

Short-lived war

Just before the substantially revised data began surfacing, highlighting the overlooked severity of the crisis, OPEC+ (a group of 23 oil-producing countries that includes Russia and Mexico), made a mistake.

Russia and Saudi Arabia surprised each other and overlooked the consequences of their actions.

For the first time since its formation in December 2016, OPEC+ failed to reach an agreement. Russia, which has led the non-OPEC group of producers within the alliance, refused to play along. Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak told reporters that, “from April 1, no one — neither OPEC countries nor OPEC+ countries — are obliged to lower production.” Saudi Arabia announced that it would put an additional 2.6 mb/d above the March ceiling into the market (with total production reaching 12.3 mb/d in April) and drastically cut its export prices. The UAE also said it would increase output by around 1 mb/d, to 4 mb/d.

Facts & figures

The media labeled the move a price “war,” variously described as launched by the Saudi kingdom against Russia, or against the U.S. shale industry, or even – in one of many conspiracy theories – by the kingdom and Russia jointly against the U.S. This “war” was, however, short-lived. In hindsight, it looks like both Russia and Saudi Arabia surprised each other and overlooked the consequences of their actions.

Oil prices were in freefall, crashing by more than 50 percent between March 1 and March 18. Brent oil reached a low of nearly $15 per barrel by the end of the month.

The U-turn

In an unprecedented move, the U.S. called on Saudi Arabia and Russia to put their differences aside and for OPEC+ to reconvene. This would have been unheard of in the past. The U.S. was never shy expressing its resentment of OPEC. In 2018, for example, the champion of the No Oil Producing and Exporting Cartels (NOPEC) bill, Republican Senator Chuck Grassley, stated, “It’s long past time to put an end to illegal price fixing by OPEC. The oil cartel and its member countries need to know that we are committed to stopping their anti-competitive behavior.”

These days, however, the U.S., the world’s largest oil consumer, is also its biggest producer thanks to the shale industry – a sector that the current administration is keen on protecting, especially now, during the presidential elections campaign.

On April 2, President Donald Trump referred to a potential cut by OPEC+ of 10 mb/d. One week later, OPEC+ announced an output decrease plan of 9.7 mb/d over two years, effective from May 2020. (At first, it said 10 mb/d, but Mexico agreed to shoulder only 100,000 b/d instead of the original 400,000 b/d allocated to it.) Furthermore, OPEC+ cuts would be accompanied by decreasing output (of somewhere between 3.7 to 5.0 mb/d) from other large producers, mainly the U.S., Canada and Brazil. That latter reduction, however, would not come from formal commitments, but declines caused by lower prices.

The order of magnitude of the agreed cutbacks and the collusion from countries that normally follow market principles, is unprecedented. It highlights the mammoth challenge faced by the oil industry. The big question is, however, whether such cuts are enough to salvage it. The answer lies in demand.

Demand story

Because of the COVID-19 lockdowns, economic growth has been hit hard. Despite a lack of consensus, all economic growth forecasts continue to paint an increasingly dire picture. In its April (2020) World Economic Outlook, the IMF projects that the global economy will shrink by 3 percent in 2020, a whopping downgrade of 6.3 percentage points from the January 2020 projection. That is a remarkable revision over a very short period.

Just like forecasts of economic growth, projections for oil demand are becoming increasingly pessimistic.

This downturn makes the “Great Lockdown,” as the IMF calls it, the worst recession since the Great Depression and far worse than the Global Financial Crisis of 2007/2008. However, the IMF cautions that such forecasts depend “on the epidemiology of the virus, the effectiveness of containment measures, and the development of therapeutics and vaccines, all of which are hard to predict.”

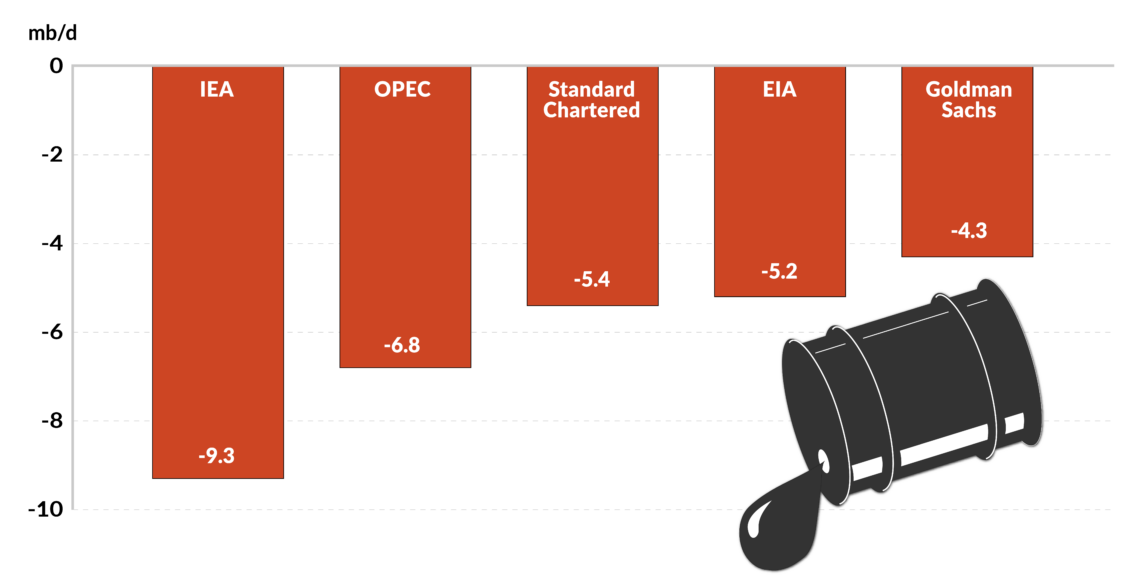

Economic activity is, by far, the most important driver of energy consumption. Just like forecasts of economic growth, projections for oil demand are becoming increasingly pessimistic, with the direst scenario to date coming from the IEA. A few days after OPEC+ announced its cuts in April, the agency predicted demand for oil would fall by a whopping 9.3 mb/d year-over-year in 2020.

OPEC projects a smaller decline – of 6.8 mb/d – and the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) puts the figure still lower, at 5.2 mb/d. Goldman Sachs expects a drop by some 4.3 mb/d. Either way, this is easily the biggest demand shock ever.

Hazy outlook

Under today’s market conditions, supply is merely chasing demand. If, over the next two years, average declines in oil demand exceed production cuts, commodity prices will come under pressure again. In a joint statement on April 17, 2020, Russian Energy Minister Novak and his Saudi counterpart Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman highlighted their countries’ readiness “to take further measures jointly with OPEC+ and other producers if these are deemed necessary.” This is, however, easier said than done. OPEC+ has not acted coherently since its formation and cheating has continued throughout.

If demand falls by less than the production cuts, prices and production may recover. Under such a scenario, U.S. tight oil, which is the first to leave the market when oil prices decline, will be the first to reenter the market, again giving OPEC+ the same headache it had over the last three years. Either way, oil-producing countries cannot expect a smooth ride. This applies particularly to those that rely on oil revenues to keep their economies afloat and need high oil prices to balance their budgets.