India-Russia relations show renewed spark

The bilateral partnership is strong but has its limits as New Delhi seeks to develop closer ties with the West.

In a nutshell

- New Delhi and Moscow have cordial relations, reaffirmed by high-level visits

- Booming bilateral trade, no criticism of the war in Ukraine highlight ties

- India may avoid closer military cooperation with Russia to placate the West

Near the end of 2023, Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar arrived in Moscow for a five-day visit that included meetings with both President Vladimir Putin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. Both sides emphasized the strategic nature of their long-standing friendship, and the Kremlin leader took the opportunity to invite Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to visit Russia.

Given India’s outspoken ambition to toe the line between Russia and the West in matters relating to Ukraine, Mr. Jaishankar needed to raise the prospect of a return to the traditional practice of annual summit meetings. The last time the two sides met was in late 2021, when President Putin met Prime Minister Modi during a short visit to India. Following the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, India has preferred to keep a low profile, maintaining the relationship but at a distance.

Mr. Jaishankar’s visit may be viewed as a sign that the traditional friendship is being cautiously reaffirmed. In the words of Manoj Joshi, a distinguished fellow at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi: “The foreign minister’s visit to Moscow emphasizes that we still have close ties but at the same time it avoids all the attention that a high-profile summit gets.” That may now be about to change. In response to a question following his meeting with President Putin, Mr. Jaishankar said he was “very confident” that a Russia-India summit will take place in 2024.

India helps ease Russian isolation

From a Russian perspective, the high-level Indian visit was a much-needed positive development, a sign that its international isolation is being broken. The very fact that President Putin does not normally meet with foreign ministers drives home the new reality that he needs as many friends as he can get.

Although the West has been frustrated by its lack of success in achieving unified international condemnation of Russia, the Kremlin has been steadily losing friends and allies because of its war on Ukraine. A case in point is Kazakhstan, which was once part of the Soviet Union. In response to the Russian aggression, it has taken important symbolic moves like increasing the official use of the Kazakh language, instead of Russian, and it has even blocked Russian television channels.

Another case is Armenia, also an ex-Soviet republic, which had been a staunch ally of Russia. Following its defeat in Nagorno-Karabakh, where Russian peacekeepers failed to intervene to prevent an Azeri victory, it has downgraded relations with Russia and instead made overtures to Europe and America.

Russia has been successful in winning support from several smaller countries in the Global South, but that falls far short of compensating for the loss of more significant friends and allies. The key question then concerns the potential impact of a reaffirmed Indo-Russian friendship. A parallel to the much-touted Sino-Russian “unlimited friendship” may provide part of the answer.

More on Russia by Stefan Hedlund

Russian arms exports in a tailspin

Russia’s emerging war economy

Nordic media take aim at Russian threats

India stays neutral on Ukraine, profits from Western sanctions on Russia

While the West has been frustrated by the Chinese refusal to condemn Russia, the Beijing-Moscow friendship has proven to be anything but unlimited. China has pounced on the opportunity to purchase Russian oil and gas, which has angered the West, but such purchases are at rock-bottom prices.

Similarly, there is mounting evidence that China is using countries in Central Asia as conduits for a booming trade with Russia, which again has angered the West. But although this trade includes large volumes of critically needed dual-use items like ball bearings, it has stopped short of supplying the weapons and ammunition that Russia desperately needs.

Absent serious military assistance from China, which could have turned the tide in Ukraine, Russia has been forced to turn to North Korea for a resupply of artillery ammunition and ballistic missiles. There is plenty of anecdotal evidence that illustrates the poor quality of this assistance, from the abysmal accuracy of missiles to artillery shells that self-eject or even detonate inside gun tubes.

The parallel to the Indo-Russian friendship is obvious in two regards. One is that, like China, India will maintain its policy of neutrality over Ukraine, refusing to condemn the Russian aggression, and the other is that, like China, it will continue purchasing Russian oil at rock-bottom prices. What remains, then, is the question of whether India may provide help on the military side. This is where the Indian visit to Moscow did provide some news.

From a Western perspective, the potential warming of relations between India and Russia comes at a point where the broader geopolitical stakes have risen to alarming levels. There is constant concern about the impact of Sino-Russian friendship on developments along the Pacific Rim, ranging from Korea and Japan to Taiwan and the South China Sea. If a warming Indo-Russian friendship were to add to the problems in the Indo-Pacific, then it would be highly unwelcome news. But is this a realistic outlook?

The prospect of closer military cooperation

The core question concerns what a warmer Indo-Russian friendship may have to offer, beyond continued Indian refusals to condemn Russian aggression in Ukraine, and the answer is – not much.

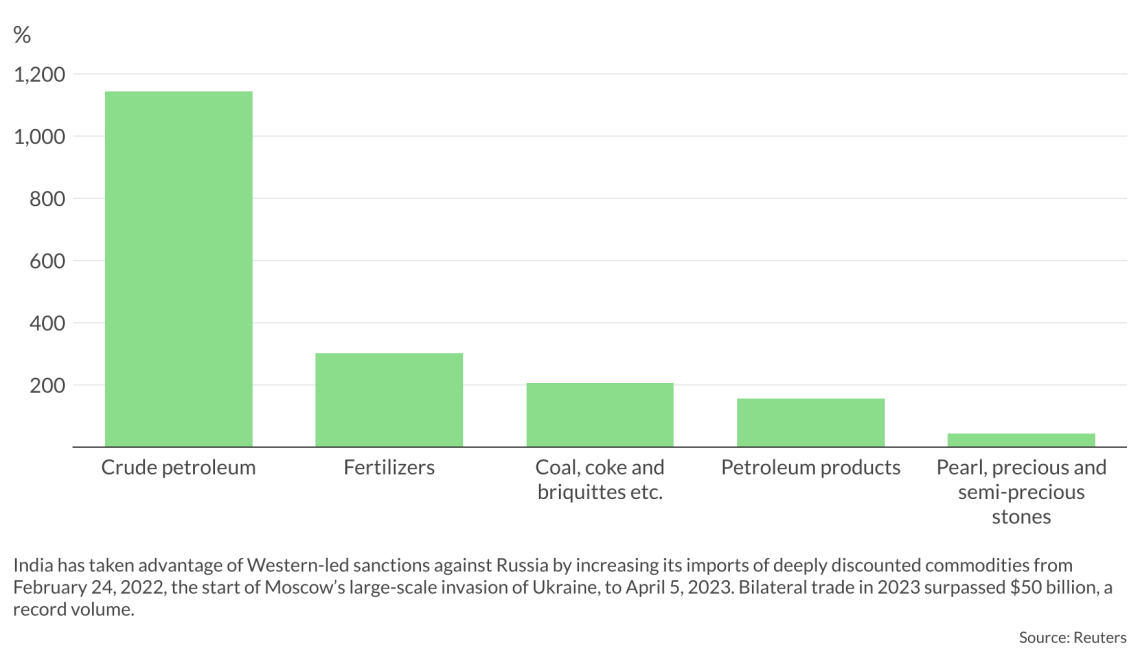

At his meetings in Moscow, Mr. Jaishankar noted that bilateral trade had hit an all-time high, likely topping $50 billion in 2023, and that trend was expected to continue: “What is important is that this trade is more balanced, it is sustainable and it provides for fair market access.”

What he failed to add was that the upward surge has been driven by trade diversion, as Russia has lost markets in the West, and that Russian purchasing power is boosted by the rise in Indian purchases of oil. It may also be added that conflicts over whether to pay in Chinese yuan or in Indian rupees have caused several oil cargoes to be diverted to China.

There was renewed talk about a north-south transport corridor that would link India with Russia via Iran. On paper, it makes a lot of sense, but in practice, it does not seem to be going anywhere. To date, it has been limited to gunrunning from Iran to Russia, and associated Iranian investment in relevant transport infrastructure.

This leaves the question of the proposed joint production of modern military equipment. If India does choose to go down that path, there will be a clear downside. For as long as Delhi has stayed on course in countering China, which is also very much in its interest, it has been able to count on the West to look the other way when it purchases Russian oil and refuses to condemn Russia in the United Nations. But if it were to extend its friendship to military cooperation, then there would be costs. So, what would the upside be?

Facts & figures

Poor performance damages Russia’s military reputation

The immediate answer is that there is none and for two reasons. One is that the abysmal performance of the Russian armed forces in the war against Ukraine has been a sobering experience even to seasoned observers. It is not only a question of poor planning and logistics. This may be viewed as a Russian problem that need not concern others. The real shock has been the poor performance of Russian weapons technology.

In the years before the full-scale invasion, President Putin made a habit of spicing his bellicose stance against NATO with frequent reference to new Russian wonder weapons, like the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, the Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile, the Zircon hypersonic anti-ship cruise missile, the Kinzhal hypersonic air-launched ballistic missile and the Poseidon doomsday torpedo. He was especially fond of touting the hypersonic missiles as invincible weapons that no American air defense would be able to counter.

During the war in Ukraine, these weapons have fallen well short of expectations. There is anecdotal evidence of ballistic missiles that misfire and land on Russian soil, and it is claimed that cruise missiles must be launched above water because misfires will then drop into the sea. Above all, when the allegedly invincible Kinzhal missile has come within reach of Ukrainian Patriot missile defenses, the kill ratio has been 100 percent.

In addition to the documented poor quality of Russian hi-tech arms, the Indian side will also have to consider the poor prospects for contracts to be honored. Given the high attrition rate on the battlefields in Ukraine, over the coming years, Russia may be expected to focus completely on production for its own needs. It has recently even been seeking to repurchase weapons sold to other countries.

In assessing whether India can realistically expect to get anything out of enhanced arms cooperation with Russia, it is important to note the shortcomings of past cooperation. Indian purchases of Russian arms were on a downward trajectory well before the war in Ukraine. According to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), between the five-year periods 2013-2017 and 2018-2022, Russian sales to India, long its largest customer, dropped by 37 percent.

The Indian government has instead begun looking for weapons from the West. In 2023, it contracted with Germany’s ThyssenKrupp for six new submarines and funds were made available for the purchase from France of three additional Scorpene class submarines and 26 Dassault Rafale marine fighter jets.

It is possible that India still believes that it stands to gain from renewed arms cooperation with Russia, despite the poor track record. One should not underestimate the importance to the Modi government of the “Make in India” program, which is geared toward making India a manufacturing hub. In his comments at the Moscow meeting, Mr. Lavrov made specific reference to the program: “We are respectful of the aspirations of our Indian colleagues to diversify their military and technical links. We also understand and we are ready to support their initiative to produce military products as part of the ‘Make in India’ program.”

Scenarios

Unlikely: Closer military cooperation

It is possible to envision a scenario in which the two sides embark on substantial cooperation in modern arms production. India would derive benefits from Russian know-how and, in return, offer Russia a greater role in the Indo-Pacific, which in turn would influence Russian relations to the Global South. But that is not very likely.

Likely: New Delhi will keep Moscow at a distance

A more likely interpretation is that the Indian interest is driven by a perceived need to keep up with and counter Sino-Russian military cooperation. China and India have after all been at war before, and the risk of further clashes cannot be discounted.

Although the Chinese side must be having the same second thoughts about the quality and reliability of Russian weapons, there are indications that there are remaining isolated niches of Russian technology where the Chinese side feels it can still gain some value. From an Indian perspective, it may seem useful to get inside the Russian military-industrial establishment, if only to see what may be available to China.

The main takeaway from a Western perspective is that while the prospect of a warmer Indo-Russian friendship does have an alarming undertone, the outlook remains beholden to the fact that national self-interest will trump friendship. On the one hand, fundamental opposition between India and China will ensure that the triangle will remain marred by internal opposition that limits its prospects. On the other hand, it is equally clear that fears of financial sanctions from the U.S. will constrain both Chinese and Indian support for Russia, rendering the outlook for the Kremlin rather precarious.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.