Kuwait oil: Time to catch up

Small Kuwait is sitting pretty with one of the largest known oil deposits under its surface. The colossal resource earned the emirate its staggering sovereign wealth fund. However, Kuwait faces a longer-term existential threat as the world begins to wean itself off fossil fuels.

In a nutshell

- Kuwait finds it difficult to ramp up oil production

- Its vast proven oil reserves may soon begin losing market value

- Projections show the emirate will exhaust its wealth in 50 years

During the last 10 years, Kuwait announced bold oil production capacity targets only to revise them downward later, unlike its more successful Middle East peers in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Kuwait’s ambition to reach 4 million barrels per day (mb/d) in production capacity by 2020 has been pushed back repeatedly, most recently by another 20 years.

At first sight, such a delay should not matter much for a small and rich country that has accumulated substantial financial wealth in the world’s oldest sovereign wealth fund (SWF). The size of the fund, however, is no reason for complacency. At current production levels, Kuwait’s proven oil reserves have a life span of more than 90 years. In a world that is determined to move away from fossil fuels, this asset’s value is at risk of shrinking over time, its oil reserves becoming “stranded assets.” Furthermore, as long as the country fails to diversify its single commodity economy, it risks seeing its SWF contract as well, with adverse economic and social consequences.

Resource-rich

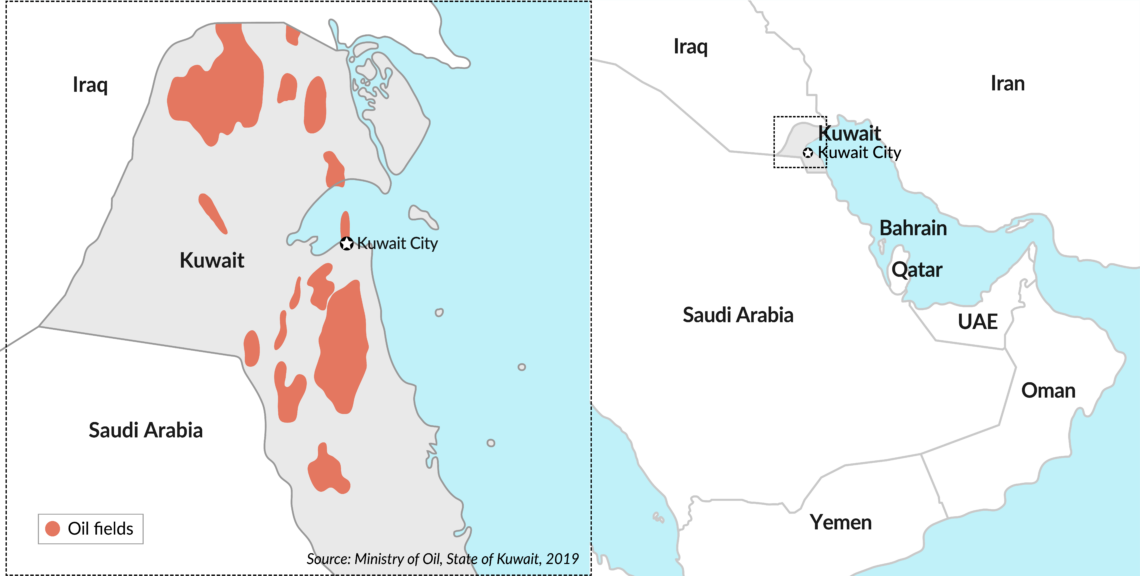

Kuwait sits on 102 billion barrels of proven oil reserves – an amount equivalent to 6 percent of the world’s total, placing Kuwait seventh in the world (after Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Iran, Iraq and Russia).

Facts & figures

Most of Kuwait’s oil reserves and production are concentrated in a few mature onshore oil fields discovered in the 1930s and 1950s. The Greater Burgan oil field, the world’s third-largest (after the U.S. Permian Basin and Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar field), accounts for most of Kuwait’s reserves and production.

Facts & figures

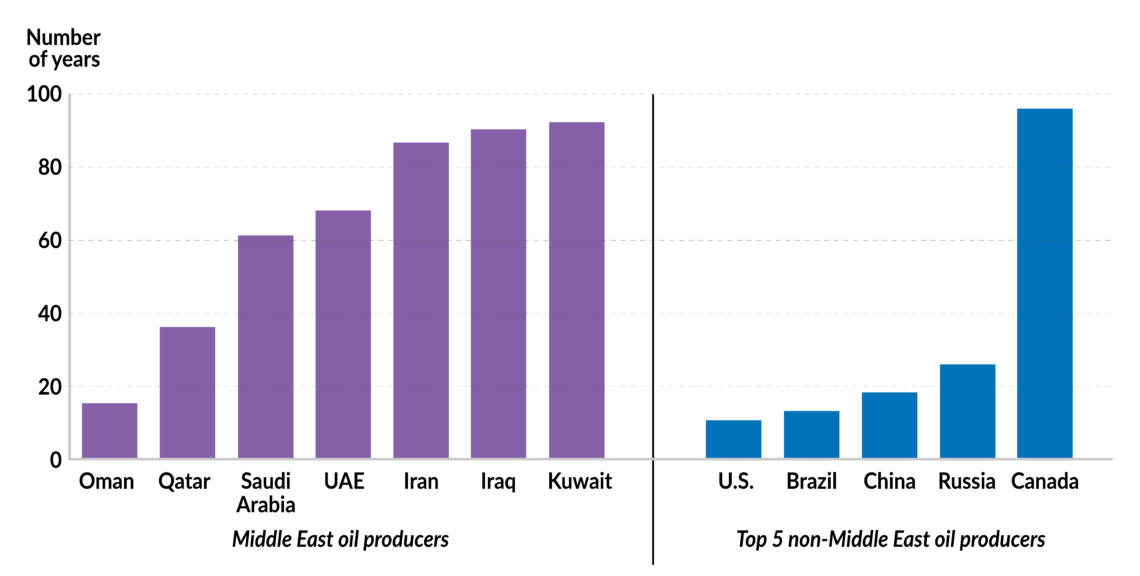

At current production levels, Kuwait’s reserves would last for more than 90 years, second-longest only to Canada’s. The question is whether these reserves will have any market value by that time.

Production

In 2019, Kuwait produced around 2.7 mb/d, or more than 3 percent of global oil. It ranked eighth in the world (after the United States, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Canada, Iraq, the UAE and China). Within OPEC, Kuwait is the fourth-largest producer (after Saudi Arabia, Iraq and the UAE), accounting for nearly 8 percent of the organization’s oil output.

What gives Kuwait greater importance, however, is the fact that, along with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the emirate has a spare production capacity estimated at around 100,000 b/d, excluding the Partitioned Neutral Zone (PNZ), whose oil resources it shares with Saudi Arabia. Such a spare capacity gives Kuwait a swing producer status, even if it is modest compared to that of Saudi Arabia’s.

The PNZ covers some 5,770 square kilometers and runs south from Kuwait along the Gulf coast. Kuwait and Saudi Arabia are sharing it. The PNZ used to produce more than 500,000 b/d, equally divided between the two states, but since 2015, production from the two main fields (Khafji and Wafra) has been interrupted because of a dispute between Riyadh and Kuwait City. In December 2019, the two states reached an agreement to resume oil production from the shared fields.

Low-cost producers such as Kuwait are typically the last to leave a shrinking market, not the first.

Given its small population, Kuwait consumes only about 15 percent of its total petroleum production; the rest of Kuwaiti oil is exported via the Strait of Hormuz. Kuwait’s exports account for around 5 percent of global oil trade, with more than 80 percent heading to Asia.

Expansion

In 2018, Kuwait announced plans to spend more than half a trillion dollars by 2040 to boost its oil and gas output and refining capacity. The plan called for $114 billion in capital outlay in the first five years, with an additional $394 billion up to 2040. About 70 percent of this expenditure has been earmarked for the upstream oil sector to help expand crude oil production capacity to 4.75 mb/d by 2040, up from 2.86 mb/d as of January 2020. Domestic refinery throughput would increase to 2 mb/d, up from 0.7 mb/d, while global petrochemical production is to triple to 16 million tons per year, also by 2040. Additionally, Kuwait hoped to increase natural gas production to 2.5 billion cubic feet a day by 2040 from just 200 million cubic feet a day currently.

Recently, however, Kuwait Petroleum Corporation (KPC), the country’s national oil company, was quoted as reassessing its capital investment plans and considering reducing its oil production target to 4 mb/d.

Some media outlets ascribed such revisions to increasing concerns about climate change and the fear that demand may not be able to absorb additional oil supplies. Such an argument, however, is hard to sell. After all, low-cost producers such as Kuwait are typically the last to leave a shrinking market, not the first.

Underperforming

Kuwait is no stranger to revising its oil production targets downwards. Almost two decades ago, it aimed to achieve a production capacity of 4 mb/d by 2020. That target was rolled over by another 20 years.

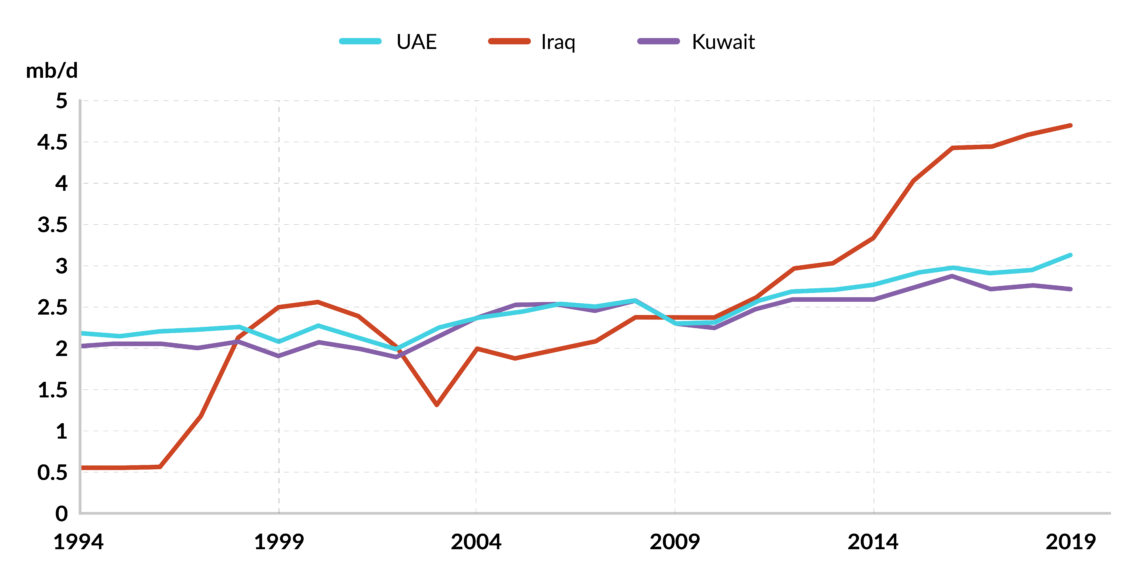

Despite its oil potential, Kuwait lags its peers in the Middle East. It took the emirate 25 years to increase production by nearly 700,000 b/d. In sharp contrast, in the last 10 years alone, Iraq has succeeded at increasing its production by more than 2.3 mb/d. Although its oil reserves exceed those of the UAE (68 billion barrels), Kuwait’s oil production has generally trailed that of the UAE and in recent years, the two OPEC members have headed in opposite directions.

Kuwait is a rare oil-producing country that remains closed to the private sector.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects Kuwaiti oil output to stay at current levels up to 2024 at least. The suspension of production from the PNZ is partly to blame. But looking at the general trend, other factors have played a more significant role.

Kuwait’s oil is not getting any easier to produce. Investment is required in enhanced oil recovery, heavy oil and offshore oil, among others, putting strains on KPC.

The Iraqi experience can provide useful insights. Iraq heavily relies on international oil companies to extract its crude. These companies have brought the capital and expertise necessary to expand Iraqi oil production rapidly. Given its vast resource base, the Iraqi government has been able to establish some of the most stringent fiscal terms with more than 95 percent effective tax rates, clearly confirming that engaging oil companies has a positive effect.

In sharp contrast, Kuwait is one of the very few countries that remain closed to the private sector, particularly in the exploration and production of oil. The industry was nationalized in 1975. Since the mid-1990s, Kuwait has made some attempts to engage international oil companies to boost production, but the issue remains politically sensitive. Take Project Kuwait, for example, which was initiated in 1997, a period of low oil prices. To incentivize investment, companies would retain control over the operational management of oil fields. However, even that aspect was considered within the emirate as ceding control to foreign investors, and the project was quickly discontinued.

In today’s oil market, with intensifying competition partly because of the additional supplies of the shale revolution in North America (enabled by a competitive market structure) and given the growing global anti-oil sentiment, it is difficult to see such a mindset persevering. Kuwait’s traditionally conservative neighbors are moving toward opening their oil sectors, whether by allowing foreign participation in oil licenses or by privatizing some of their nationally-owned assets.

Better now than never

Many would argue that Kuwait is no Iraq. In fact, Kuwait is better off than all its neighbors, given the substantial financial reserves it has accumulated over nearly seven decades.

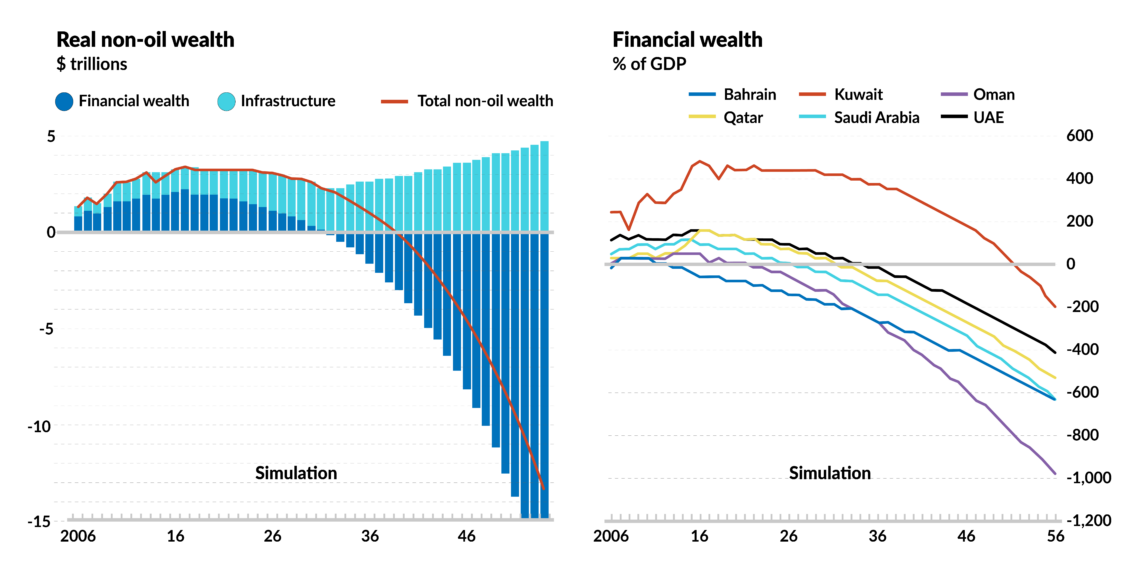

Kuwait has the world’s oldest SWF, established in 1953, eight years before the emirate achieved independence: the Kuwait Investment Board, which is known today as the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA). The fund is the third-largest petroleum fund in the world, after Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG) and Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA). Given the size of the Kuwaiti economy, according to the IMF, in a world that needs less oil, Kuwait’s SWF will help keep its net financial wealth positive until about 2052.

Facts & figures

However, there are two critical reasons why Kuwait should not be complacent. Firstly, its economy is significantly dependent on oil, as diversification attempts have had limited success.

Petroleum accounts for over half of the emirate’s GDP, 92 percent of export revenues, and 90 percent of government income. In an increasingly competitive oil market, the resulting lower prices will weigh heavily on the Kuwaiti economy – especially if not compensated for with an expansion in production. Under such a scenario, the savings of the SWF will be shrinking and withdrawals will be increasing, eventually draining the fund’s capital, especially if its interest earnings do not suffice to cover government spending.

Secondly, given the long remaining life span of Kuwait’s oil reserves, the intensified commotion over climate change and the pressure to ease the world’s dependence on oil, the emirate faces a bigger risk of stranded assets than its neighbors. Countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been investing generously to expand their oil production capacity over the next two decades – highlighting their determination to convert below-ground assets into financial wealth sooner rather than later, before their value dissipates. After all, what is the point of sitting on some of the world’s largest reserves if nobody wants them?