Clientelism makes a mockery of nonaligned policy claims

Many African leaders’ claim of neutrality in Russia’s war on Ukraine cannot be squared with their reliance on Wagner mercenaries and aligning with Moscow’s global agenda.

In a nutshell

- Africa has good reason to keep political distance from the Ukraine war

- However, dependence on Moscow draws the continent into the conflict

- Wagner mercenaries deepen Africa’s instability and governance ills

Among the unforeseeable consequences of Russia’s full-bore invasion of Ukraine is how it has trained the spotlight on Moscow’s presence in Africa. The continent is being drawn into the conflict raging in a theater that appears distant. More than 18 months after the Russian invasion began, the position of African countries toward that war and Russia’s conduct in it has shifted from touting their “nonaligned” status to trying to extricate themselves from complicity in barbarism that directly threatens the global food supply network.

In the United Nation’s March 2022 vote on a resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, 28 out of 54 African countries supported the measure. Seventeen African countries voted to abstain – including South Africa, Algeria and Angola – and eight countries did not submit a vote. One, Eritrea, joined Russia, Belarus, North Korea and Syria in voting against the resolution.

During the war’s first months, African states distanced themselves from it, arguing that the conflict had no bearing on their material interests or peace and security in the continent. Further, African capitals took Western powers to task by reminding them of ongoing conflicts in Africa and demanding a global response to these tragedies that would be no less robust than the West’s reaction to the events in Ukraine.

African countries caught in a trap

The posture of nonalignment adopted by African states in the earlier months of the war may seem prudent and morally defensible. African governments were hardly interested in becoming proxies in conflicts and tensions involving major global powers such as Russia, the United States and China.

There were some notable variations in how different African states interpreted the terms of their nonalignment, sometimes in line with the level of their dependence on Russia. South Africa emerged prominently among the regional players with excessive exposure to Russian economic and business interests and political culture. That quickly has translated into Pretoria adopting a nonaligned stance that borders on abetting and supporting Russian efforts in Ukraine. So exposed, South Africa consequently finds itself used as a tool in Moscow’s push against the Western pressure to isolate Russia in Africa and globally.

Even with different permutations of nonalignment across African states, the position was generally meant to convey that Africa was not directly involved in the Ukraine conflict and did not desire to be drawn into it. As the war progressed, however, African capitals had to recognize how the war constrained the global supply chain, including the supply of grain needed to maintain food security for impoverished African nations.

Not ready to condemn the aggression

While the harm to the global food supply network did not necessarily turn African states against Russia, it inspired some criticism of the far-reaching economic consequences of Russia’s conduct in the war. However, they stopped short of condemning Russian President Vladimir Putin for launching an avoidable conflict, and Africa’s stance on the war remained unchanged. When the relationship with Russia was at stake, refusing to take sides in Moscow’s war of aggression posed no moral dilemma for African leaders.

Read more on Russia and Africa

Russia returns to Africa

Unity eludes Southern Africa over Russia’s war

The failed Wagner mutiny changed this all at once. It has focused attention on Africa’s nonalignment posture, bringing the bloodletting in Ukraine much closer to Africa’s doorstep. The role of Wagner in hotspots across Africa suddenly gives rise to ethical doubts. The exposure of Russia as a country that relies excessively on a mercenary group to extend its grip on Africa’s security theater introduces awkward questions about Africa’s complicity in long-term instabilities in the region.

No free lunches from the Kremlin

This directly leads to another brutal query – about the extent to which the nominally nonaligned policies entail supporting Russia’s global agenda. The Wagner group has, over a decade, emerged as a force to call when it comes to procuring ruthless security assistance to regimes and embattled rulers in Africa. That assistance is usually required by fragile states with a history of persistent internal conflicts, pointing to the desperate shape that many countries in the region are in – on the brink of failing if not already failed.

With some African countries entangled with foreign mercenaries as the security situation in the region deteriorates, the claim of nonaligned is untenable.

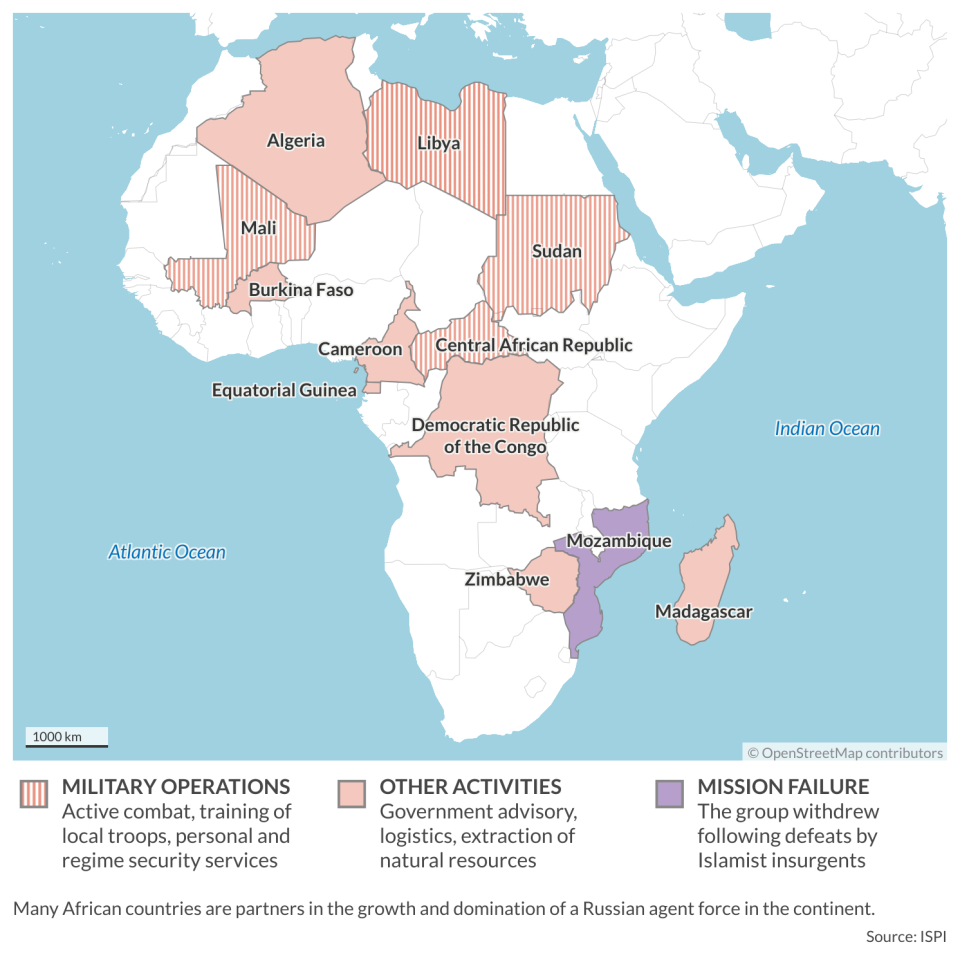

This sad reality turns the nonaligned narrative upside down, giving it a different meaning when considering how this position has effectively advanced Russian interests by propping up Wagner on the continent. With some African countries entangled with foreign mercenaries as the security situation in the region deteriorates, the claim of nonaligned is untenable, given that African countries are partners in the growth and domination of a Russian agent force in Africa.

Ultimately, this partnership sustains the broader Putin-Wagner agenda as it manifests itself in the war in Ukraine and other areas such as Libya and Syria. Africa is eventually drawn into different theaters of conflict by its association with Russia and Wagner. That removes the idea of impartiality from the nonaligned posture expressed by Africa regarding the invasion of Ukraine.

Facts & figures

Now tied up with the survival and maintenance of Wagner in Africa, African countries need to explain how this does not leave peace and stability on the continent at the mercy of non-state actors sanctioned by international conventions to which Africa is a signatory. Wagner was actively involved in conflicts in Mali, Sudan, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mozambique and, most recently, Niger – where coup perpetrators reportedly appealed to the Russian mercenary group for armed assistance as the regional body, Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS) is threatening to intervene militarily.

If anything, Africa is a strategic cash cow for the group, and trends show Wagner expanding in the continent. After the mysterious air crash that killed Wagner’s top leaders, it appears that more formal Russian government structures will take the organization’s place. The United Nations International Convention Against the Recruitment, Use, Financing, and Training of Mercenaries, adopted in 1989, prohibits states from using or associating with mercenaries because of the destabilizing effect on fragile states and democratic consolidation.

Illegal and harmful activity

In addition, the Organization of African Union (OAU) – now the African Union (AU) – Convention of Elimination of Mercenaries in Africa also prohibits states from supporting mercenary activities in any conceivable form. Article 6 of the Convention implores states to “Prevent entry into or passage through its territory of any mercenary or any equipment destined for mercenary use.”

While other African countries, such as South Africa, have deployed troops to strengthen regional response to conflicts in line with regional and international rules, using mercenary or paramilitary groups that operate outside the law’s ambit undermines such initiatives. However, even harder to understand and justify is the relationship South Africa has cultivated with Russia in the face of revelations regarding how Russia’s foreign policy in Africa is pushed through Wagner.

African states cannot maintain indifference about the conduct of a party whose agenda is harmful to the continental vital interests.

It is next to impossible to extricate the significant part of Russia’s agenda in Africa from the Wagner group and its ways of doing things, practically and philosophically. Russia’s expansion in Africa coincides with the retrenchment of Western powers in the region, notably in the Sahel region, where developments have left very little doubt regarding the methods and consequences of this change. African states reserve the right to stand aside in tensions that they see as primarily involving major global powers. However, it is worth questioning whether this should go so far as African states sustaining their neutrality position where such pressures are detrimental to peace and stability in the continent. Further, it smacks of hypocrisy for African states to maintain indifference about the conduct of a party whose agenda is harmful to the continental vital interests, let alone be seen fraternizing such a party, as is the case with Russia.

Scenarios

African leaders’ stark choice

As the deceitful relationship that the Russian Federation built with the Wagner group has become public knowledge, it has shaken the African leaders who are beginning to appreciate the long-term implications for peace and stability in their region. Pressure from Western powers for African states also has accelerated the awakening process. At long last, African leaders are becoming more cautious about relations with Russia.

The recent Russia-Africa Summit (held in July 2023 in St. Petersburg) showed Africa’s position toward Russia as becoming fragmented further across the continent. Barely a third of African leaders attended the event. Among those who flew to St. Petersburg, the focus was mainly on food security and the grain corridor deal, not showing solidarity with President Putin and support for his war.

The deterioration of security in the continent from successive coups leaves African leaders with a stark choice. They can rethink the role of such actors as Russia and assert their own agenda for peace and stability – or condemn African states to remain clients of the world’s leading powers. Ultimately, the latter scenario would render the pretense of nonaligned policies an immoral farce, as is the case today.