Paraguay: Awakening from a long slumber

Known in Latin America as a backwater haven for criminal enterprises and eccentric dictators, Paraguay began to turn around over the past decade. The country’s elite is taking steps to strengthen state institutions and improve the rule of law.

In a nutshell

- Paraguay is the world’s biggest producer and exporter of hydropower per capita

- Foreign sales of soybeans are another engine of economic growth

- These benefits of the globalized economy and a desire to attract FDI have mobilized Paraguayan elites to tinker with reform

For generations, Paraguay was a small backwater state in the interior of South America. The last decade and a half, however, witnessed surprising changes as the country’s economic fortunes were buoyed by the global commodities boom. Limited reforms have been introduced by the ruling elite to facilitate trade and foreign investment. Whether Paraguay makes a further transition to democratic modernity may hinge on the global economic climate.

The country has been known as a setting for novels, including Graham Greene’s The Honorary Consul and Augusto Roa Bastos’s prizewinning I, the Supreme, which portrayed the 19th-century dictator Jose Gaspar Rodriguez de Francia. Friedrich Nietzsche’s sister, Elisabeth, came to Paraguay with her husband Dr. Bernard Forster in 1887 to found Nueva Germania, a colony to preserve the “Aryan Race.” They failed.

Off to a poor start

Paraguay won notoriety in the 19th century for a series of particularly megalomaniacal dictators. The first, Francia (1814-1840), tried to seal off the country from the outside world. His successor, Carlos Antonio Lopez (1841-1862), turned outward with a bellicose posture, and his son and successor, Francisco Solano Lopez (1864-1870) recklessly involved Paraguay in a geopolitical contest between Argentina and Brazil. The result was a war that remains the bloodiest in South America’s history. The nearly six-year-long slaughter cost Paraguay two-thirds of its male population and big portions of its territory.

Not quite a century later, the Paraguayan dictator of the day got into a war with Bolivia over a chunk of empty, arid lowland between the two countries known as Chaco Boreal. In that conflict, Paraguay won back some territory. Since then, the country has been ruled by a series of strongmen representing the National Republican Association – Colorado Party (Partido Colorado, or ANR-PC), the best-known of which was General Alfredo Stroessner (1954-1989).

World Bank studies suggested that Paraguay had been underpaid by nearly $1 billion per year.

Paraguay is also notable for its unique ethnic composition. Some 95 percent of its people identify as mestizo, a mix between European settlers from the Spanish colonial period and the indigenous Guarani people who preceded them by at least a millennium. Nine out of 10 Paraguayans speak the Guarani language and many locations in the country are named in that language. It is the only case in Latin America where the elites and those who consider themselves white, self-identify as mestizo and speak the language of the area’s indigenous people.

Facts & figures

Paraguay, vital statistics, 2017

- Independence from Spain 14 May 1811

- Territory 406,752 square kilometers

- Climate Tropical to temperate

- Natural resources Hydropower, timber, iron ore, manganese, limestone

- Population 7.0 million, most residing in the eastern half of the country

- Government system Presidential republic

- Legislature Bicameral National Congress with 45 senators, 80 deputies

- Council of Ministers Appointed by the president

- GDP (official exchange) $38.9 billion

- Budget deficit -1.1% of GDP

- Public debt 19.5%

- Inflation rate (consumer) 3.6%

Source: CIA World Factbook

As a base for continued economic growth, landlocked Paraguay has exploited its position between two great river systems, the Parana and Paraguay, by joining with its neighbors in the construction of two gigantic hydroelectric power plants. Together with Brazil, it built the world’s second-largest dam on the Parana River in Itaipu, which began generating power in 1984. The Yacyreta Dam power plant, built with Argentina, went on the grid a decade later. These two installations have made Paraguay the world’s biggest producer of hydropower per capita and proved to be a fabulous source of income. In 2018, for example, Paraguay consumed only 5 percent of the power generated at Yacyreta and exported the rest of its half share to Argentina. Similar proportions apply at Itaipu, with the excess power being sold to Brazil.

Facts & figures

Paraguay learned to benefit from its geographic location

These energy sales constitute nearly a third of the total value of Paraguay’s exports. However, despite the stipulation in the original investment agreements that Paraguayan hydropower should be exported at a “just price,” just what that price should be has been in dispute for many years. World Bank studies suggested that Paraguay had been underpaid by nearly $1 billion per year for the past two decades. In 2018, Argentina’s President Mauricio Macri negotiated directly with his Paraguayan counterpart to resolve the issue by forgiving a significant Paraguayan debt from the dam’s construction and adjusting the price of the power sold to Argentina.

Bad guys’ paradise

Paraguay has been also South America’s contraband haven. From the 1930s to the 1970s, during the era of closed economies in Argentina and Brazil, it was the continent’s center of duty-free exports and smuggling. That expertise was put to new use beginning in the 1970s, when drug trafficking became a booming industry and many other forms of organized crime capitalized on the country’s strategic position to conduct illicit business. The critical location was the Triple Frontier, where the borders of Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay come together at Ciudad del Este.

Walking the streets of that city was like finding oneself in the first Star Wars movie, at that scruffy bar in Mos Eisley spaceport, a place where all the bad guys in the galaxy could be found. By the 1980s, cells of Hezbollah and other terrorist groups had set up shop in Ciudad del Este. It was almost certainly from there that Hezbollah carried out two devastating terrorist attacks, in 1992 and 1994, against the Jewish community in Argentina.

Paraguay is one of the last countries in the region to retain diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

Today, change is afoot in Paraguay. Perhaps it can be attributed to the Chinese-led commodities boom. Perhaps the political elite wanted more than a sleepy economy with a world-notorious den of iniquity could provide. Beginning about a decade ago, Paraguay’s government, still in the hands of the hegemonic Colorado Party, began a concerted effort to make the rule of law more secure and transparent for all to see. The purpose of these changes was to attract foreign investment.

Today, Paraguay derives about 85 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) from foreign trade. As a result, its ruling elite must follow new rules of the game. Interestingly, Paraguay is one of the last countries in the region to retain diplomatic relations with Taiwan – even as the value of its exchange with the Peoples’ Republic of China is increasing.

Economy, stupid

When Mario Abdo Benitez took office as president of Paraguay in August 2018, his goals were to maintain the economic growth that the country had enjoyed for more than a decade and to make government institutions more transparent. He is much more likely to achieve the first objective than the second.

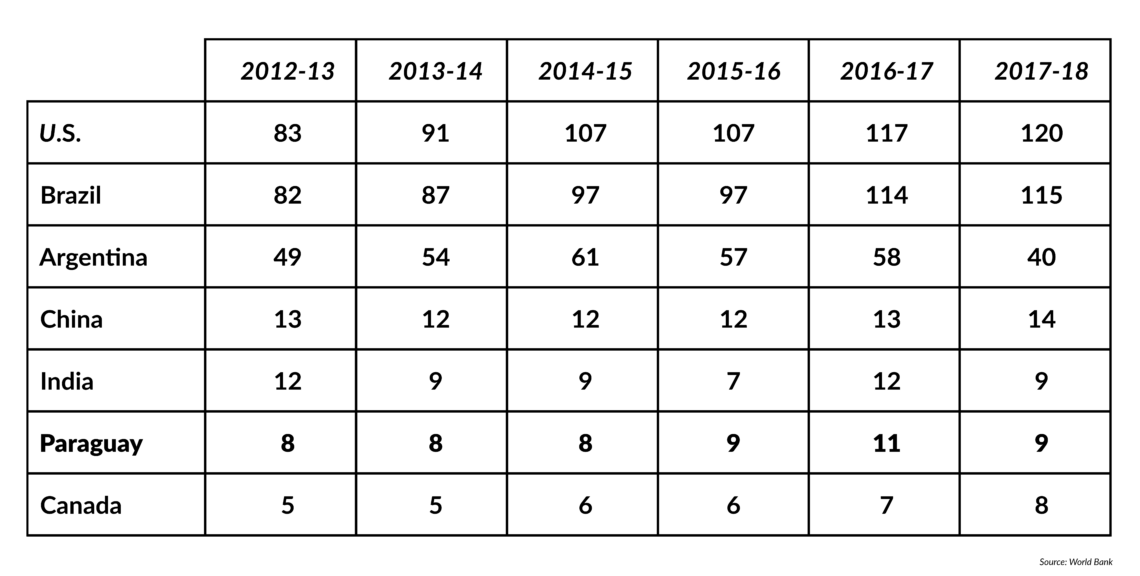

Paraguay has been democratic since the ouster of President Stroessner in 1989. Its democracy remains, however, of rather poor quality. At the same time, the country’s economy has transformed dramatically in the past decade and a half. While the principal engine of this economic success has been soybean exports, the whole agricultural sector has flourished. The forestry industry is also doing well. Soybean sales abroad had soared from little more than 1 million tons in 1990 to nearly 11 million tons in the 2016-2017 season, when a drought in Argentina increased demand for the product.

Facts & figures

Production of soybeans (main world players, in millions of tons)

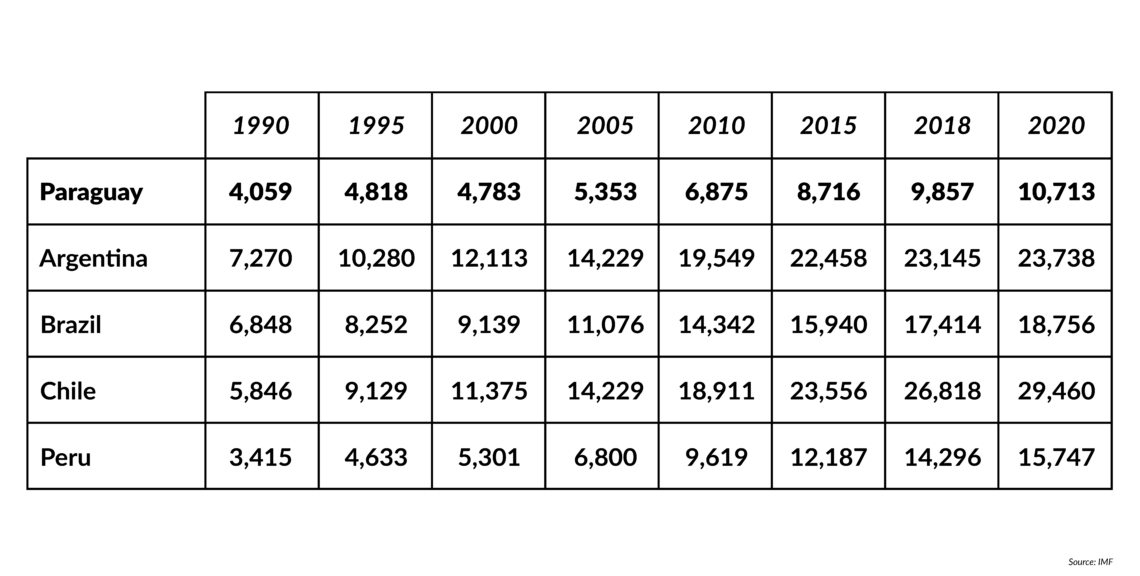

If expansion continues at the current clip, Paraguay will soon enter the club of “middle-income countries,” as classified by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It is one of the least-known success stories in the hemisphere.

The unique element of this economic surge is that while an improved legal framework has boosted the agriculture sector, the country’s political institutions remain weak, corruption-ridden and limited in their capacity to sustain a competitive electoral process. The critical issue, therefore, is whether the Paraguayan elite will continue reforming the country or stop short of a complete overhaul.

Impressive growth

Paraguay’s development is even more remarkable when one considers the political instability and economic stagnation of its much larger neighbors, Argentina and Brazil. In contrast to their malaise, according to the IMF, the Paraguayan economy expanded at an average rate of 6.05 percent between 2008 and 2018 and topped out at a rate of 11 percent in 2010, the highest pace of development in the world that year. Its GDP increased from $29.98 billion in 2004 to $72.7 billion in 2018 (PPP, not nominal). During that period, poverty was reduced by nearly 50 percent and the middle class almost doubled. The Central Bank of Paraguay offers similar computations.

Facts & figures

Income per capita ($ in purchasing power parity, 1990-2020)

The dramatic expansion of soy cultivation has been accompanied by an increasingly ambitious institutional framework that includes environmental protection. In the new production area northwest of the capital city, Asuncion, the norm was established that for every 100 hectares deforested for agriculture, 15 hectares must be maintained in natural vegetation. Remarkably, given the traditional inefficiency and opacity of the Paraguayan bureaucracy, both state and private actors agreed to abide by these standards. A public-private consensus has also been achieved on respecting property rights. This is especially critical as most investment in expanding Paraguay’s agricultural output has come from outside the country.

Meanwhile, the illicit activities in Ciudad del Este go on as if soybeans did not exist.

Weaker institutions

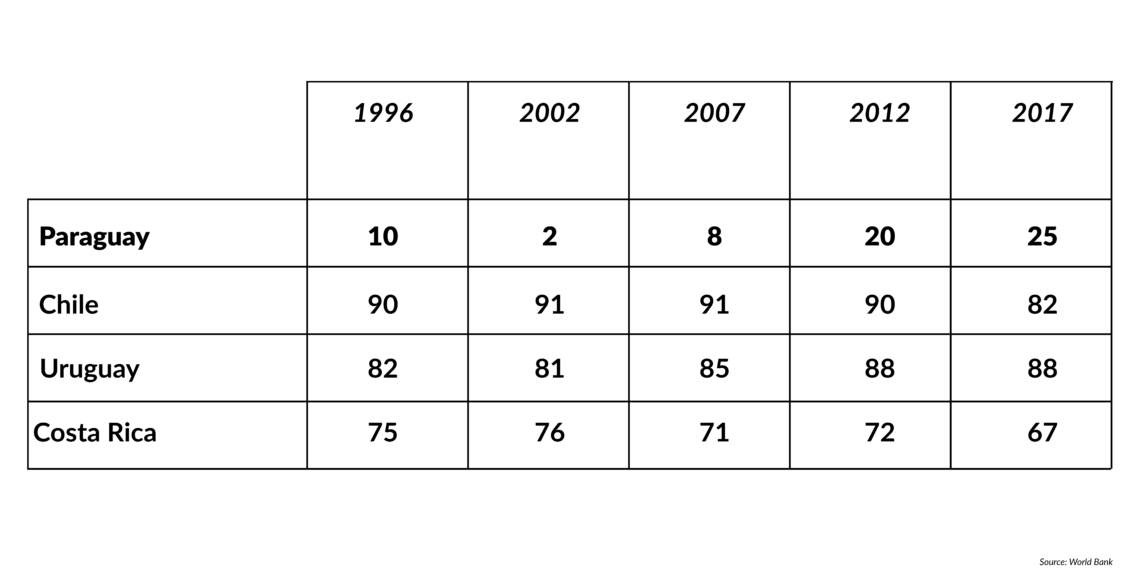

Compared to Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay – the Latin American countries with the most stable and effective institutions – Paraguay still has a long way to go in terms of democratic governance. At the same time, the progress it has made on the World Bank’s scoresheet for political stability and violence avoidance is quite substantial.

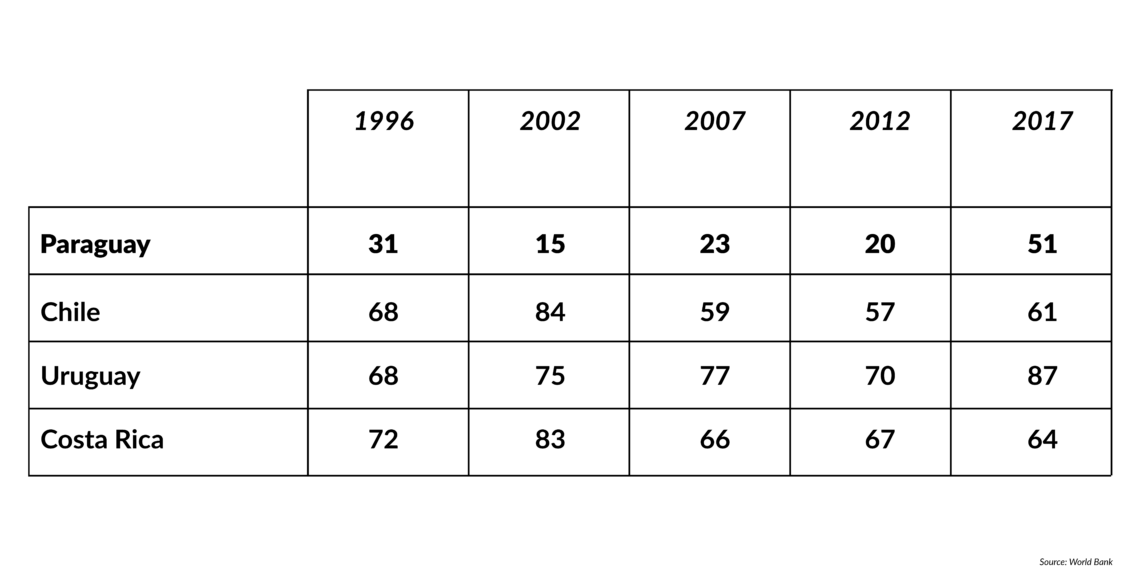

Facts & figures

World Bank stability ratings

(Scores based on absence of political instability, violence or terrorism)

Look at Paraguay and Chile. In 1996, at the beginning of the export boom in both countries, Chile scored 68 (out of 100) points in this category, while Paraguay only 31 points. By 2017, Chile had backslid to 61 points while Paraguay advanced to 51. A considerable gap remains, but the distance between the two countries has noticeably diminished. (Chile’s lower score reflects the government’s recent strong-arm tactics in disputes with the indigenous Mapuche people, while Paraguay’s improved rating rewards its newfound determination to address the problem of international terrorists in the Triple Frontier area.)

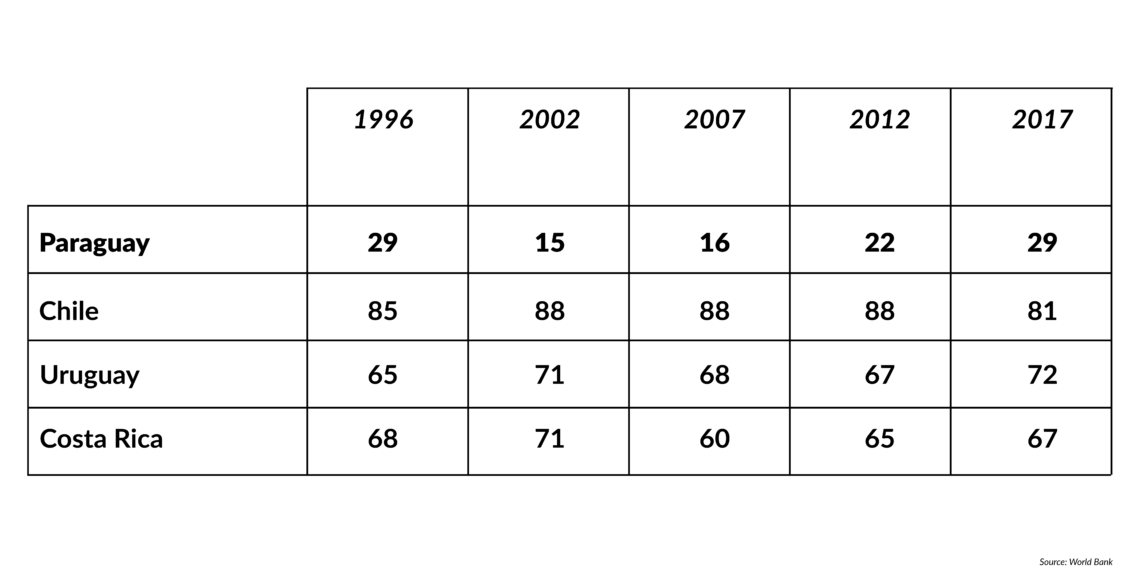

Facts & figures

World Bank corruption ratings

(Scores based on effectiveness of anti-corruption efforts)

In other areas, such as transparency and corruption control, Paraguay’s progress is significant, but it remains well behind the region’s leaders.

Without a stronger commitment to the rule of law at home Paraguay will not widen its role in the global economy.

The final table assesses the rule of law. Here, too, advances have been made over the past decade, but Paraguay is still found lacking when compared to the most stable and lawful nations in the region. The principal obstacle to further improvement is a deep-seated tradition of corruption and an opaque state apparatus that operates at the whim of a closed political and economic elite.

The progress already made and the hope for future export growth powered by foreign investment form a powerful incentive for Paraguay’s elite to continue reforming the country’s weak institutions and to tackle the problem of corruption. Without a stronger commitment to the rule of law at home, however, Paraguay may find it challenging to widen its participation in the international economy.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is that Paraguay will continue cautiously along the path it has chosen. If the price of soybeans continues to rise, as it has over the past two years, expansion of the area under cultivation will continue as well. The pace will depend entirely on foreign direct investment (FDI), with much of these capital inflows coming from China. That should serve as a sufficient incentive to keep improving the country’s regulatory framework.

Although it appears much less likely at the moment, a reverse scenario involving a sudden decline in the price of soybeans would have an immediate negative effect on Paraguay’s economic expansion. This, in turn, would undermine the governing ANR-PC’s current belief that it has a stake in reforming the country. It would then be up to the elite to decide whether to continue experimenting with modernity or relapse into the familiar old mode of corruption and opaque governance.