World race to self-sufficiency in strategic manufacturing

Global value chains have been shrinking for a decade; the pandemic has only accelerated the process. Western countries are now racing to reshore parts of their strategic manufacturing and make supply chains more resilient. China, meanwhile, continues its quest for dominance.

In a nutshell

- Global value chains in manufacturing are under pressure

- Governments want to limit economic reliance on China

- Companies want to streamline logistics and curb risks

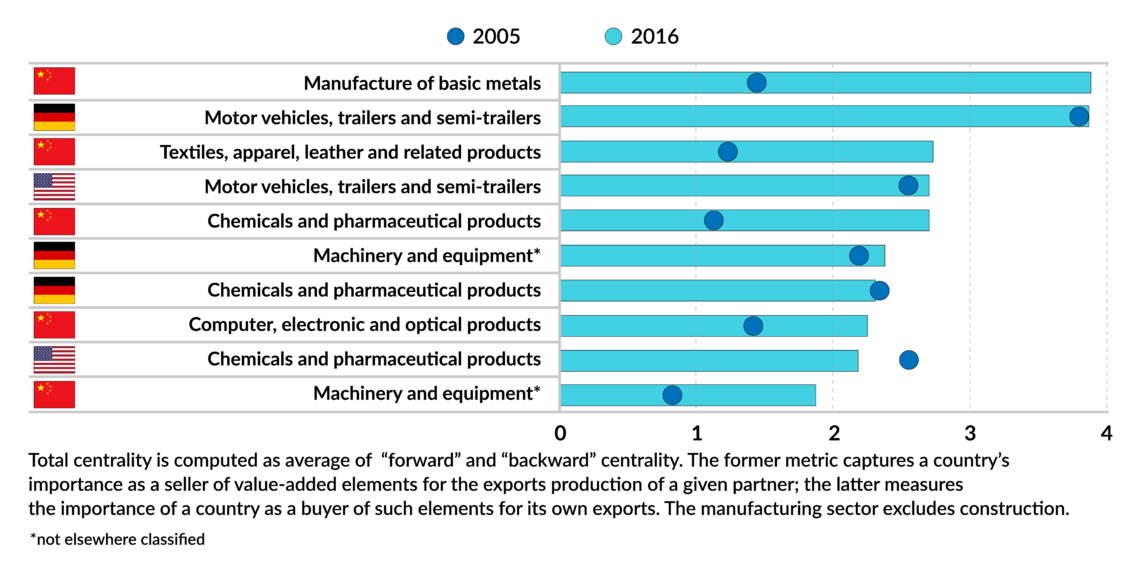

The last decade was marked by the rethinking of global supply chains. Excessive reliance on just one or a few suppliers or export markets, coupled with political tensions, economic nationalism and trade protectionism, forced global value chains (GVCs) to become more regionalized. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), goods crossing the ocean reached their peak around 2011.

Since then, the foreign value-added content of exports has gradually fallen for many major economies, and the expansion of GVCs has stopped. In some sectors, though, a few Asian countries, especially China, maintained their central role as the main manufacturing hub. The Covid-19 pandemic revealed the fragility of GVCs in such sectors. It showed, for example, excessive reliance on China and other Southeast Asian countries for medical supplies and devices. It also exposed logistics, transport, labor and other difficulties that may appear in fragmented GVCs, putting into question the applicability of the “just-in-time” concept. The surge of trade restrictions around the world further worsened the situation.

Reshoring part of manufacturing to advanced economies could improve social and environmental standards of production.

Disruptions and shortages of specific products forced governments in large economies to examine critical dependencies and reconfigure strategic GVCs. Such decisions include diversification of suppliers and reshoring manufacturing, bringing part of the industry “back home.” According to the OECD, special emphasis in policy discussions worldwide is given to food, basic pharmaceuticals, electronic equipment and motor vehicles.

To counter China’s nonmarket-oriented policies, the European Union and the United States plan to adopt similar strategies: increasing government support, restricting technological flows and building national champions in strategic sectors. China, on the other hand, is betting on domestic production in critical sectors and reducing dependence on foreign supplies and technology.

Facts & figures

With the World Trade Organization losing its significance and the multilateral enforcement mechanism still paralyzed, there are no efficient ways to question anticompetitive practices. In this scenario, an uncontrolled race to self-sufficiency in strategic economic sectors may worsen global economic imbalances. Simultaneously, reshoring part of manufacturing to advanced economies could be beneficial, as it could potentially improve social and environmental standards of production.

Strategic sovereignty

In February 2021, the U.S. initiated a comprehensive review of American supply chain vulnerabilities, beginning with a 100-day review of four key products facing shortages: semiconductors, large capacity batteries, critical minerals and active pharmaceutical ingredients. The administration of U.S. President Joe Biden has also started a one-year review of supply chain vulnerabilities for the industrial bases in the following sectors: defense, public health and biological preparedness, information and communications technology, energy, transportation and supply chains for agricultural commodities and food production.

The EU is preparing similar studies and is already starting to unveil policies that will help build self-sufficiency or increase the availability of inputs and technologies in the sectors mentioned above. Both the U.S. and the EU see China as central to their strategies. The U.S. calls China its “strategic competitor” and “the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system.” The Biden administration plans to actively pursue wider economic and technological decoupling with China, building alliances with other advanced economies to counterweight Chinese hegemony.

The EU is adopting a less confrontational and more nuanced approach. The European bloc has recently concluded negotiations of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China, which aims to remove regulatory obstacles for increasing investments of EU companies in China. In some sectors, Western economies’ push toward self-sufficiency collides with China’s strategy to secure supplies. Semiconductors and rare earth elements are the most notable examples. Semiconductors are essential for everything that is electronic or digital, and rare earth oxides, metals, and magnets are powering the global production of modern machinery.

The EU has joined the race, calling chips essential for its ‘digital sovereignty’.

According to data published by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), 75 percent of the world’s chip manufacturing is concentrated in East Asia. Taiwan’s TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung are the largest semiconductor companies, responsible for 55.6 percent and 16.4 percent of the global production, respectively (data from TrendForce). China, which today is a net importer of microchips, is projected to have the world’s largest share of microchip production by 2030 due to an estimated $100 billion in government subsidies.

SIA reports that U.S. companies account for 48 percent of the world’s microchip sales, but U.S. factories account for only 12 percent of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing, down from 37 percent in 1990. A bipartisan Chips for America Act, introduced in the U.S. Congress, proposes $23 billion in potential funding and tax credits for the advanced semiconductor sector through 2026.

The EU has joined the race, calling semiconductors essential for its “digital sovereignty” and announced plans to increase local manufacturing, which today represents less than 10 percent of the global production in value, to at least 20 percent by 2030. Both the EU and Americans are in talks with Taiwanese and Korean companies about opening new production facilities on their territories.

A similar race to secure supplies is happening in the rare earth sector. Although mining has been increasing in the U.S., Australia and some other countries, around 80 percent of the global refining of rare ores and production of magnets takes place in China. Beijing is studying measures to control 17 rare earth minerals’ production and export. It also plans to secure, by 2025, a 50 percent share in the world’s electric and hybrid vehicles’ production, which uses rare earth metals and magnets. The U.S. and EU are looking for ways to revive domestic production or secure non-Chinese supply of rare earth elements.

Costs and benefits of reshoring

The costs of reshoring manufacturing to advanced economies could be considerable. According to SIA, depending on the type of facility, a new semiconductor factory in the U.S. could cost approximately 30 percent more to build and operate over 10 years than one in Taiwan, South Korea, or Singapore, and 37-50 percent more than one in China. As much as 40-70 percent of that cost differential is directly attributed to government incentives.

Reshoring would fail to shelter economic actors from uncertainty as interconnected supply chains usually show more resilience.

These costs are high mostly because of the need to create specific technical skills and acquire knowledge that does not exist today in advanced economies. There are also costs associated with higher labor and environmental standards. OECD adds that despite higher costs for businesses and consumers, reshoring would fail to shelter economic actors from uncertainty. More interconnected supply chains usually show more resilience.

Nevertheless, the new European and American strategies have positive aspects. The EU’s declared objectives are “more sustainable and fairer globalization” and “promoting responsible and sustainable value chains.” The U.S. is adopting a similar approach, placing climate change and human rights at the core of its foreign policy and its actions to rebuild supply chains.

From an environmental perspective, re-localization can bring important advantages. With less fragmentation of production, there will be less “carbon leakage,” with advanced economies importing less embodied carbon from countries with a higher tolerance for pollution. For example, the OECD estimates that from 2005 to 2015, net imports of embodied carbon (CO2) into OECD countries fell from just under 2.2 to 1.6 gigatons.

Facts & figures

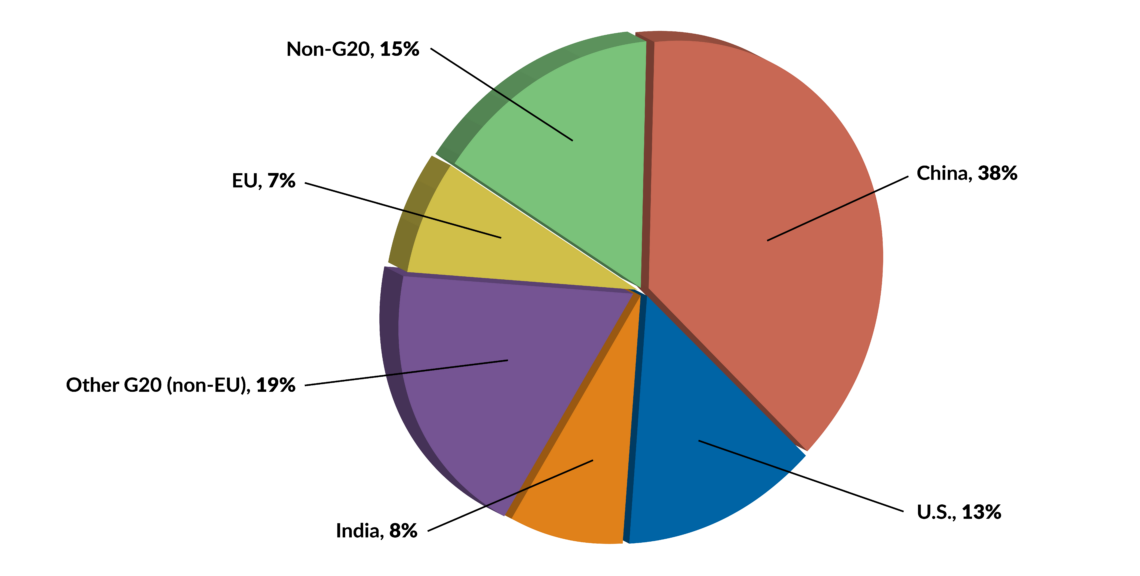

Specialists say that China’s new Five-Year Plan lacks the drive to reduce emissions. The country has yet to officially submit its revised “nationally determined contributions” (or specific commitments) for 2030 under the Paris climate agreement. The International Monetary Fund estimates that China will account for 38 percent of projected baseline carbon emissions in 2030. The U.S.’s predicted share is 13 percent, and the EU’s 7 percent. Both U.S. and EU actions to make supply chains more sustainable will be essential so that the world stays on track with warming targets established by the agreement.

Ultimately, a significant portion of the higher costs of reshoring could be a premium paid by consumers for having products that foster a fairer and greener world. From a political standpoint, it may be challenging to explain the price increase caused by this strategy.

Scenarios

Global economic development in the next decade will be defined by the U.S. and Europe’s attempts to find non-Chinese supply alternatives, build domestic production facilities in strategic sectors, and make supply chains more sustainable and responsible.

In the short to medium term, the following scenario is likely to unfold:

- China will continue its own race to self-sufficiency, competing with Western economies over access to strategic suppliers. For example, with semiconductors, Taiwan and South Korea will be sought after as strategic partners. China could try to assert political control over Taiwan, as it did with Hong Kong.

- Many countries will be caught in the middle of self-sufficiency politics and technological decoupling. Australia and Canada show how choosing to side with the U.S. can complicate a country’s political and economic relationship with China.

- Government incentives will increase exponentially in strategic sectors, coupled with more trade and investment restrictions and protectionism. This will lead to more nonmarket-oriented practices, more barriers to competition, and more economic imbalances.

- Investment in R&D and capacity building in strategic sectors will increase, as countries will need to create know-how and skills.

- Multinational companies will play an important role. The OECD estimates that 70 percent of international trade involves exchanges of raw materials, parts and components, services for businesses and capital goods that firms use to produce and serve their customers. Multinational enterprises do one-third of the world’s production and account for half of the global trade. Advanced economies, which still dominate the list of Fortune Global 500 companies (although it now features 124 Chinese companies), will increase regulatory standards for enterprises to make GVCs greener and more responsible.

- Vaccine diplomacy will be an important tool. The U.S. plans to vaccinate its adult population by the end of May, having set July 4 as its target for returning to normality. Together with its $1.9-trillion stimulus package, this paves the way for a rapid economic recovery. Soon, the U.S. will be able to compete with China, which was the first to recover from the pandemic and to use vaccine politics when building alliances with other countries.

- The rest of the world will probably start recovering only in 2022-2023. Trade disruptions in strategic sectors are likely to continue. The race for self-sufficiency will further increase stockpiling and risk of shortages in the near future, increasing costs and causing concerns for companies and consumers.