The Arab world faces China’s ambitions

China is engaging in a quiet but determined Middle East diplomacy, seizing diverse opportunities to expand its influence with Arab governments and peoples.

In a nutshell

- The Middle East holds economic, diplomatic and cultural appeal for China

- Beijing seeks to woo Arab states leery of a new Cold War

- Western powers will seek to contain China’s influence

A Chinese proverb says that the best conduct in war is beating your opponent without having confronted him. China’s diplomacy in the Middle East has thus been progressing patiently, without vehemence or hype, but with an obligation to achieve results under Beijing’s national Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

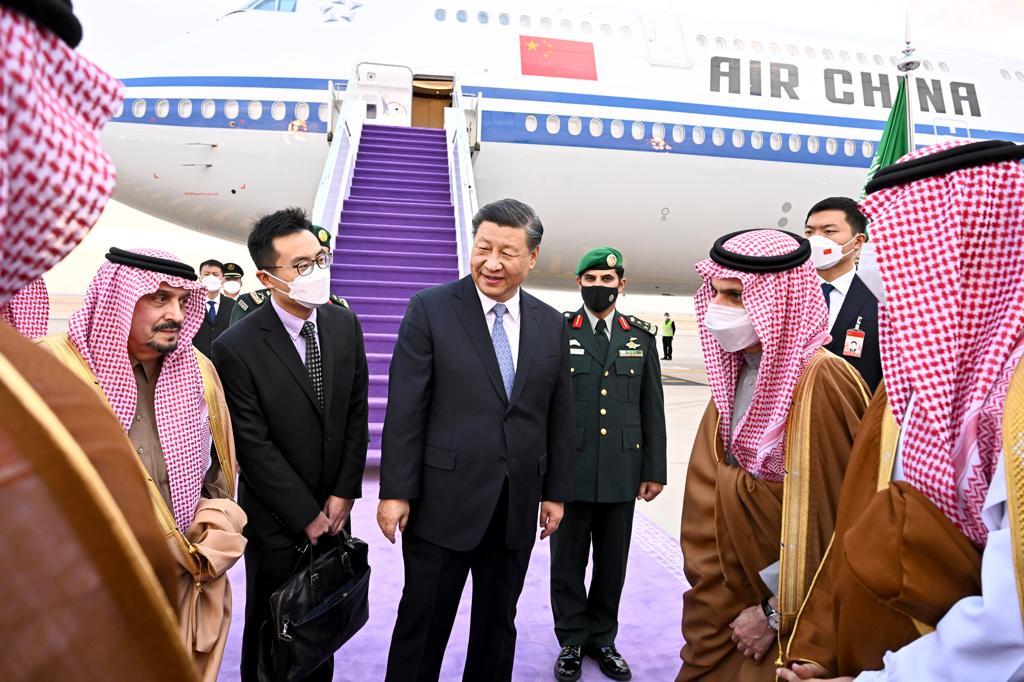

The 2022 China-Arab States Summit and the China-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Summit, held last December in Riyadh, were the result of a long process of reflection and diplomatic efforts toward engagement. China outlined its policy toward the Arab world in a 2016 policy paper, which outlined plans to develop relationships with key Middle Eastern states in order to develop strategic hubs. Beijing now sees the current regional context as favorable. Former colonial powers are in the midst of an economic crisis; Moscow is busy with war in Europe; and Chinese experts are convinced that the United States has entered a period of decline. They are focused on an eventual U.S. withdrawal from the region – a scenario discussed periodically in Washington think tanks, and one that would present a real opportunity for China.

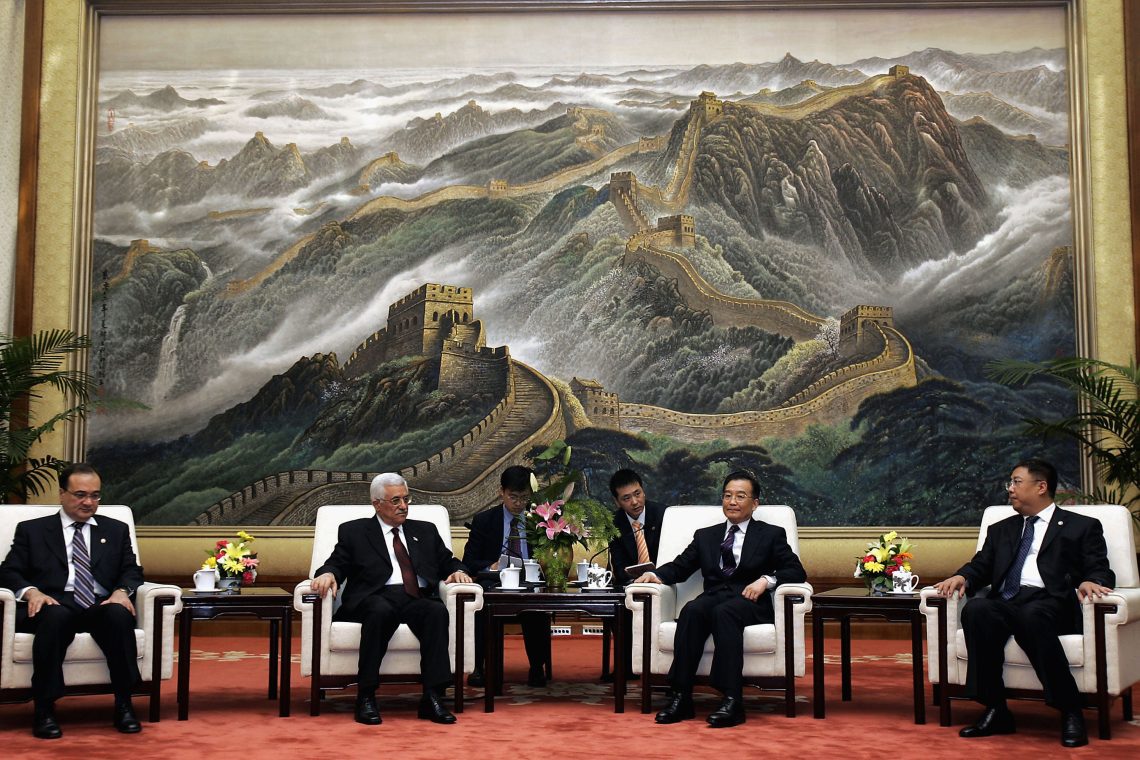

Unlike in financially bankrupt states, where China practices a kind of diplomacy of smiles and money printing, its approach in the Arab world is more subtle. China has understood that money does not buy everything: politics is paramount. To that end, Beijing has prepared the ground by offering to contribute to resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Middle Eastern dignitaries are received with honors in Beijing’s Zhongnanhai Pavilion, with past visitors including the presidents of Turkey and the Palestinian Authority and leaders of the Kurdish cause.

Behind-the-scenes diplomacy is carried out in the Syrian insurrectionary zones controlled by Islamist rebels, some of whom are branded terrorists by the United Nations and who are in direct contact with the Islamic Party of Turkestan, which China considers an extension of its Uighur minority. China is shifting from its noninterference posture with extreme caution, forging ties with formal and informal actors across the region.

Long term foundation

Selecting Riyadh as the venue for last year’s summit was not a trivial choice. Beijing has understood the special role of Saudi Arabia as the guardian of Islam’s holy places. If only for symbolic reasons, it must transcend political quarrels and crises. Similarly, China presents itself as a power without enemies that practices “pragmatic cooperation.” This reassuring message is addressed to both Arab populations and Chinese Muslim minorities. China hopes that strengthening its ties with the Gulf states will help mitigate accusations of crimes against humanity against the Muslim Uighur population made by the United Nations and others.

China is probably genuine when it says it seeks stability for the BRI. While access to fossil fuels is a central factor, it does not explain everything. Beijing knows that the Arab market is dynamic and hungry for consumption.

Its diaspora is already in place, notably in the United Arab Emirates, where there are 300,000 Chinese nationals and 4,000 businesses. Small and medium-sized businesses globally have weathered successive crises under Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine, but the Gulf is one of the few regions in the world that saw accelerated growth in 2022.

Beijing has understood the special role of Saudi Arabia as guardian of Islam’s holy places.

The other, less discussed but equally essential Chinese strategy involves laying objectives for the long term. Economic performance requires modern port infrastructure along sea lanes between Asia and the West. Beijing is developing special relationships in BRI countries to avoid red tape and fragmented supply chains. Now the world’s largest user of the Suez Canal, it has signed contracts with the Suez Canal Authority, which manages all navigation activities, and is investing locally, for example in building tug boats. The objective is clear: to become a privileged partner rather than just a customer.

The safety of Chinese ships at sea is also a factor. The deployment of China’s 40th and 41st naval escort forces in the Gulf of Aden to protect its commercial lines has not been renewed in 2022 because it is too cumbersome and costly. Beijing prefers to cooperate with states that have port access to share the task of securing the high seas. This helps with cost savings, and incidentally promotes warships like the 167 Shenzhen destroyer, which has already engaged in anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, or the Type-928D assault boats designed for coastal protection.

Chinese officials present themselves to the Arab world as “equal” economic partners, not as a superpower. This official line is at times belied on the ground. U.S. intelligence agencies have reported to their Emirati allies that work has begun on a secret Chinese military base in the port of Khalifa. When the information leaked, the project was stopped cold. The Americans are watchful because they know the Chinese will need runways for their fighter jets, including the Chengdu J-20 Weilong (Mighty Dragon), a fifth-generation stealth aircraft that has stoked fears in the Pentagon. Beijing already has a base in Djibouti, but there is no indication that it will be enough for its defense ambitions.

Curiosity and prudence

China’s rhetoric of noninterference may be disingenuous, but it is successful. The Arab world is concerned about the specter of a new Cold War set off by the Ukraine crisis: one defined by two-way geopolitics and an almost obligatory choice between allegiance to the East or the West. None have forgotten that the former Soviet Union abandoned its supposed Arab “brothers” when the Berlin Wall fell. As for American interventions, they have brought down dictators but left behind unresolved civil wars.

Some in the region certainly view Chinese power as manageable. Despite the vast gap in gross domestic product, the Gulf states have considerable fossil wealth and financial resources. They do not see themselves holding weak positions at the negotiating table. Moreover, Riyadh and Beijing share a penchant for giant initiatives, such as Saudi’s “Neom” project, a $500 billion high-tech city-region planned to be built in the desert by 2030. Chinese companies are already pre-positioned to cooperate on this pharaonic site.

Arab countries are aware of the drawbacks of the Chinese model, which melds the two opposing ideas of communism and capitalism. They have watched Beijing maneuver in Africa, taking control of natural resources and quietly influencing the policies of African states. Arab countries are as clear-eyed about this rapprochement as they are intrigued with the Asian dragon, a former land of famine that has become a global economic power.

Their perception includes a fascination with the industrial prowess of an Asian country capable of manufacturing nuclear missile silos in record time – but also a skepticism of its ability to resolve conflicts in the Middle East or to deal with sensitive relations between the Saudis and Tehran, with which Beijing has signed a $400 billion strategic partnership. These expectations are not exclusive to the region’s governments; the Arab population is also concerned. A rare Saudi opinion poll found that 57 percent of residents believe the relationship with China is “important,” compared to 53 percent for Russian ties and only 41 percent for the U.S.

The Gulf monarchies are pursuing a strategy of balance. The idea is an old one, anchored in the region’s culture: that of a third party, bridging Asia and the West. To achieve it, Riyadh is prepared to make strong gestures, even if they are not very well-received in Washington. The Sino-Saudi oil agreements signed in November were thus denominated in yuan, not in American dollars. For its part, Qatar, a traditional ally of Washington, has just concluded a $60 billion liquefied natural gas deal with China.

Days after the December Riyadh summit, U.S. President Joe Biden announced an upcoming tour of sub-Saharan Africa. The American leader would arrive on a continent where China is the largest trading partner and holds a third of foreign debt (worth $696 billion). Mr. Biden’s aim will be to strike a contrast with China – promoting not just a $55 billion investment plan, but an entrepreneurial philosophy that emphasizes the private sector and respect for labor standards. He will attempt to demonstrate that American business ethics are unlike China’s, which are unbothered by human rights abuses, over-indebtedness and risks of industrial interdependence. This discourse will be addressed to African populations as well as to Arab observers, with a simple message: there is an alternative to partnering with China.

Scenarios

There are two scenarios moving forward. In the first, China further digs into its diplomatic strategy in the Arab world. It assumes a “third voice,” playing on the weariness of Arab populations in the face of the Russia-U.S. confrontation. Beijing builds its credibility by investing in vital regional issues, like the energy transition, access to water, and health challenges. It manages to transpose its status as an economic power into that of a mediator and “impartial” interlocutor, beginning to intervene in the region’s major geopolitical issues: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, negotiations on the Iranian nuclear program, the inextricable civil war in Yemen and others.

In the second scenario, the U.S. and its ally Israel mobilize their Abraham Accords partners, the UAE and Bahrain, to contain China’s economic inroads in the Middle East. A strategy of containment is pursued to fend off Chinese diplomats and limit Beijing’s presence to economic activities in nonstrategic sectors, like consumption, manufactured products and the transportation of goods. Washington reluctantly accepts the Arab argument for diversifying economic partnerships, but the U.S. administration prepares for the future. It develops forward-looking military scenarios in the event of a China-Taiwan conflict that would necessarily involve the U.S. The American objective would be to block China’s New Silk Road, by neutralizing Chinese footholds in the Middle East and North Africa.