Belt and Road: The Asian perspective

The Belt and Road Initiative has had a broad impact across Asia and beyond. Up to $1 trillion has been committed to projects, with the goals of bridging economies and opening Chinese companies to new markets. Although outside criticism will likely change the nature of new projects, the core features of the BRI will remain the same.

In a nutshell

- The BRI has created new infrastructure and trade flows

- It has taken heat from Washington and some recipients

- Future projects may be leaner, but core features will persist

Since it was launched in 2013, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become the most extensive bilateral development financing mechanism in the world.

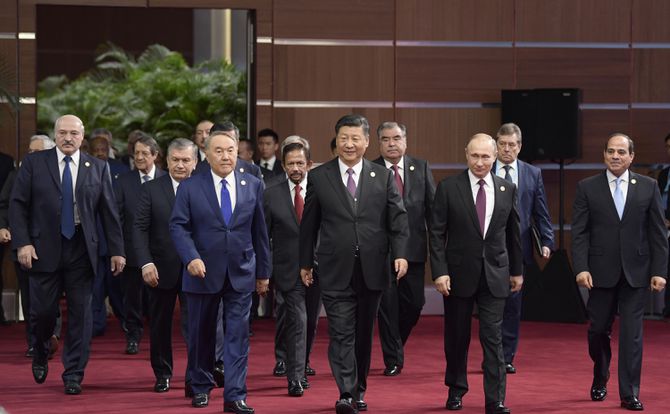

From the start, it had several internal and external drivers. When Chinese President Xi Jinping first assumed his post, the BRI was the kind of policy that could ensure his legacy in Chinese and world economic history. The project’s mission is “building a community with a shared future for mankind.” According to official documents, it seeks to bring economies, peoples and cultures closer through investment and cooperation in policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, trade, and people-to-people.

All this is not simply for the global good; historically, with the Silk Road, China was one of the significant centers of trade, knowledge and power. Undoubtedly, one of the aims of the BRI is to make China a new economic superpower in the 21st century.

Open for business

The second factor in establishing the BRI was the fact that the rapid growth of Chinese companies, mainly state-owned enterprises (SOEs), required foreign markets. The “state capitalism” peculiar to China, its explosive growth and economic influence, is making many uncomfortable — at least in terms of perceptions and potential impact, if not imminent reality. On the other side, billions of much-needed funding in infrastructure was offered in soft loans or development assistance, and later as equity investment, together with a broader cooperation agenda.

The BRI offered exclusive deals for Chinese companies, especially SOEs, just as Japanese companies used to use the government’s official development assistance (ODA) to bid under soft loans to developing countries and as South Korean companies still do today.

The rapid growth of Chinese companies needed new foreign markets.

From one perspective, the BRI is a business proposition that helps Chinese companies grow their businesses while also addressing the actual needs of recipient countries. This type of Chinese funding existed before, but after the announcement of the initiative, it has become much bigger and more systemic.

The third driver is related to financing. The existing regional and global development finance institutions, such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or World Bank, are part of the Bretton Wood institutions and their decision-making is dominated by the United States and its European and Asian allies. While China is becoming a significant contributor to these institutions, its influence inside their structures will not be commensurate with those of the traditional powers.

The BRI, together with new multilateral institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), are proposed by China and headquartered there, and can create parallel mechanisms for international cooperation. Substantive coordination and collaboration have been pledged from both sides, but on the ground, it is only beginning, mostly as People’s Bank of China’s contributions to IMF programs. In the meantime, these institutions are growing in global reach. By 2019, AIIB membership has expanded from 57 countries to 93. China has already signed 173 cooperation agreements with 125 countries and 29 international organizations under the BRI framework.

Broad reach

The scope of BRI implementation in just six years is breathtaking. According to the official BRI information portal, Western China is now connected to Western Europe by an expressway through Kazakhstan and Russia. The southern Chinese city of Kunming is connected to Bangkok. Railway connections include China-Laos, China-Thailand, Hungary-Serbia, Djibouti-Addis Ababa, Mombasa-Nairobi and Jakarta-Bandung, all either completed or in the process and funded under the BRI.

The projects launched in Pakistan alone, one of the largest BRI funding recipients, include the Gwadar Port and the Gwadar Free Trade Zone, sections of the Peshawar-Karachi Motorway and Karakoram Highway, the Lahore Orange Line Metro, and several power plants. The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan highway and China-Vietnam Beilun River Bridge II are all completed. Upgrading of the Piraeus Port in Greece has been finished and its Phase III construction is next.

The Khalifa Port Container Terminal Phase II in the United Arab Emirates was also completed and investments have been made in Walvis Bay port, Namibia. Along the China-Russia crude oil pipeline, sections of the Eastern route of the China-Russia natural gas pipeline will enter into service in December 2019, and the entire link will be completed by 2024. The China-Myanmar oil and gas pipelines have also been completed.

Trade flows

Besides billions in infrastructure connectivity, under a trade facilitation framework, the China-Kazakhstan Khorgos International Border Cooperation Center, the China-Laos Mohan-Boten Cross-Border Economic Cooperation Zone have been built and more are planned or under construction. Customs clearance time for agricultural products at the borders between China and Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan have reportedly been reduced by 90 percent. Already, Kazakhstan is emerging as a potential large meat exporter to China, with American producers such as Tyson preparing to invest heavily to mitigate the United States-China trade war.

Besides these completed or ongoing projects, very significant regional projects are in the pipeline, such as the upgrade of Pakistan’s Karachi-Peshawar Railway Line, the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway, and the China-Nepal cross-border railway.

In addition to bilateral BRI funding from the Chinese government, the AIIB alone has 35 approved projects in 13 countries all over the world. In terms of people-to-people relations, 38,700 students from BRI countries have studied in China on Chinese government scholarships. Confucius Institutes and classrooms operate in 54 BRI countries.

The overall impact of the BRI had been tremendous, as many countries near and far away from China have utilized its funding to resolve long-standing infrastructure bottlenecks that could not otherwise get financed. A World Bank study, cited in BRI official documents, attributes a 4.1 percent increase in trade in 71 countries to the initiative.

The total investment committed for BRI projects is reportedly a mind-boggling $1 trillion for over 1700 projects, spread out all over the world and funded through loans, direct investment and aid. Even accounting for all the projects mentioned above, only a fraction of this funding has so far been utilized.

Alongside loans, according to official sources, direct Chinese investment to BRI countries has reached $90 billion, including $15.6 billion only in 2018. One important direct investment source, the Silk Road Fund, was established by the Chinese government with $40 billion funding in 2014 and a further injection of 100 billion renminbi. It has already contracted $11.8 billion and invested $7.7 billion and has dedicated joint-funds such as one for China-Kazakhstan ($2 billion dedicated) and China-EU ($500). The China Export & Credit Insurance Corporation also plays a significant role in these projects, with a portfolio of $600 billion in exports and investment in BRI countries.

Backlash

The most significant criticism of the BRI, especially by Washington, has been that it corners the recipient countries into debt traps to achieve some long-term geostrategic goals. Despite the establishment of the Silk Road Fund and attempts to promote direct investment and address developmental bottlenecks, many BRI projects so far have come as sovereign loans from the Chinese government to a recipient government. Ultimately, it was the recipient government’s obligation to pay it back, not the specific projects invested.

There is a noted concern in some recipient countries about BRI-funded projects.

The case of the Sri Lankan port of Hambantota, which was transferred to Chinese-Sri Lanka joint venture to service the debt obligations of the Sri Lankan government, has made world headlines. Even though funding for the port began almost a decade before the BRI, the port encapsulated all the typical criticisms of the initiative: it was very large in size, it employed sovereign debt invested into a commercial project, and earlier feasibility studies had raised doubts about its efficiency and economic sense.

These types of bilateral loans were a feature of ODA long before the BRI. Every industrial nation has these types of bilateral lending programs, in addition to multilateral institutions such as the ADB, the World Bank, the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development, and many others. Every developing country can name an ODA project funded by many of these organizations and bilateral donors that lacked in feasibility and didn’t perform as planned. As criticism of China increased, the Chinese government countered that, for instance, the Philippines had twice the bilateral loans from Japan as it does from China.

It is clear, however, that there is a noted concern in some recipient countries about BRI-funded projects. Accusations of higher pricing, corruption and poor economic logic have already led to political fallouts. Most visibly, in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Malaysia and the Maldives, infrastructure projects funded under the BRI became hot election topics. Incumbent governments lost elections there, though not only because of Chinese-funded projects.

Strategic implications

There is one more aspect that is now creeping into the debate. In Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port case, the issue was raised of China’s geostrategic footprint: its government had become the owner, through an SOE, of a large port in the Indian ocean on an important global maritime route.

Pakistan, a long-standing ally of the U.S., has had much more tumultuous relations with the U.S. in the last decade and during this period relied heavily on China for its financial needs. The changing dynamics of the relations were highlighted by the Trump administration’s decision to cancel military aid to Pakistan in 2018 over the lack of effort by the latter to root out terrorism in the areas bordering with Afghanistan.

Referred to as the “String of Pearls,” ports invested through BRI in Djibouti, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Myanmar, Nairobi, Mozambique and Kenya now connect China to major trading regions. In some of these ports, the presence of China’s military has been negotiated. Hence the BRI has been viewed by major global and regional players as evidence of China’s increasing geopolitical influence.

Scenarios

Due to these developments, the dynamics of the BRI may change. Firstly, experiences such as in Sri Lanka's port certainly impact future decisions. The financial difficulties alone of the project could seriously affect the image of the BRI, which the Chinese government certainly doesn’t want to be tarnished. International perceptions are critical to China’s growing clout.

Secondly, the Communist Party of China is not immune to political pressure, both domestically and internationally. The fact that vast amounts are being spent in places far away from China could influence domestic opinion. Even the most internationalist and globalist country does not have a public that would unequivocally support significant sums being sent abroad. Tensions in partner countries, growing with the expansion of the BRI, will also need to be mended. In some countries, it can seem to spill into thinly-veiled, racist anti-Chinese rhetoric on social media or official speeches.

Thirdly, the recently established international development assistance agency in charge of aid projects as well as initiatives like the AIIB are very likely — in the thoroughly methodical approach of modern PRC bureaucracy — to follow the path of development banks in Japan, South Korea and institutions such as the EBRD, ADB, and World Bank. The projects under the BRI are likely to undergo much more scrutiny from Chinese institutions. Commercial, economic, environmental and social impacts are likely to become more prominent in decision-making processes. This approach is expected to be adopted on loan projects as well.

Fourthly, the Chinese government is already pledging to fight corruption in BRI projects and engaging recipient countries. Greater institutionalization and more coordination of law-enforcement, combined with a sharper focus on this specific problem, is likely to bring results, as most of the implementing companies are Chinese SOEs more likely to heed the political line.

It is a fair guess that future projects are much likely to be leaner, focused on more critical destinations, and much more in line with policies considered prudent globally.

However, the core feature of the BRI — sovereign as a borrower — is unlikely to change for a very simple reason: private investment in infrastructure in developing countries is in short supply. The initiative is focused on infrastructure and in most developing states, only SOEs and governments have the capacity to borrow for such projects. Moreover, even the most developed countries have difficulty funding infrastructure projects through private funding. For many reasons, including the inability of developing countries to create a regulatory environment for public-private partnership projects, China is not alone in focusing on sovereign infrastructure loans.