Sweden’s pivotal role in critical materials for Europe

Amid Europe’s drive for sustainability and autonomy, Sweden emerges as a rare metals pioneer aiming to challenge China’s dominance.

In a nutshell

- Europe needs stable rare-metal supplies for climate goals, geopolitical risk reduction

- China’s dominance prompts Europe to reassess mining, processing needs

- Sweden aims to play a strategic role in Europe’s rare metal diversification

For Europe to reach its climate and sustainability goals while reducing geopolitical risk from dependence on a single autocratic superpower, it needs a stable supply of rare metals. Sweden, a rare earths pioneer, seeks to play a strategic role.

“Lithium and rare earth metals will soon be more important than oil and gas,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said in her 2022 State of the European Union address. This displayed an awareness in Brussels that to stay relevant, the bloc must overcome bureaucracy and think geostrategically regarding critical mineral supply chains.

Europe, while countries worldwide are de-risking from China, is reassessing the importance of mining and mineral processing. In March 2023 the EC presented its proposal for the European Critical Raw Materials Act, a regulatory framework for the safe and sustainable supply of critical raw materials. In December, the European Parliament approved it; the act was adopted by the European Council in March.

To develop cutting-edge industries, economies need stable supplies of rare metals. Critical raw materials, including rare earth metals needed for digital development, security and the green transition, are of growing interest to great powers; in particular to China and the United States in the context of their technology race.

This also applies to the EU. While tensions rise over defense and economic policies between democracies and authoritarian states, it is possible that major powers will try to secure their access to rare metals by entirely different methods than the conventional trade practices of the globalized world. This creates a significant risk of a resource war for strategic raw materials.

If the EU is to have some degree of autonomy, it must hurry to secure access to deposits of the 17 rare earth elements.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), annual demand for various critical metals and minerals will increase from roughly 7.5 million tons in the 2020s to 28 million tons by 2040. In a scenario aiming for net-zero emissions in 2040, the IEA’s forecast surges to 43 million tons.

These materials are used in semiconductors, monitors, lasers, camera lenses, catalysts, strong permanent magnets, batteries and nuclear power rods, as well as in cancer treatment and in equipment for X-ray and bone density diagnostics.

Europe’s rare earth sourcing

Today, the EU imports the metals primarily from China, which is by far the world’s largest extractor and refiner of rare earths. This, however, is problematic for several reasons. Production in China poses risks both for the environment and human health. It also jeopardizes the EU’s sustainability goals, since the necessary production – for example, of wind turbines and batteries for electric cars – is completely dependent on China. As a result, rare earth metals are now on the EU’s list of raw materials at risk of becoming scarce.

Facts & figures

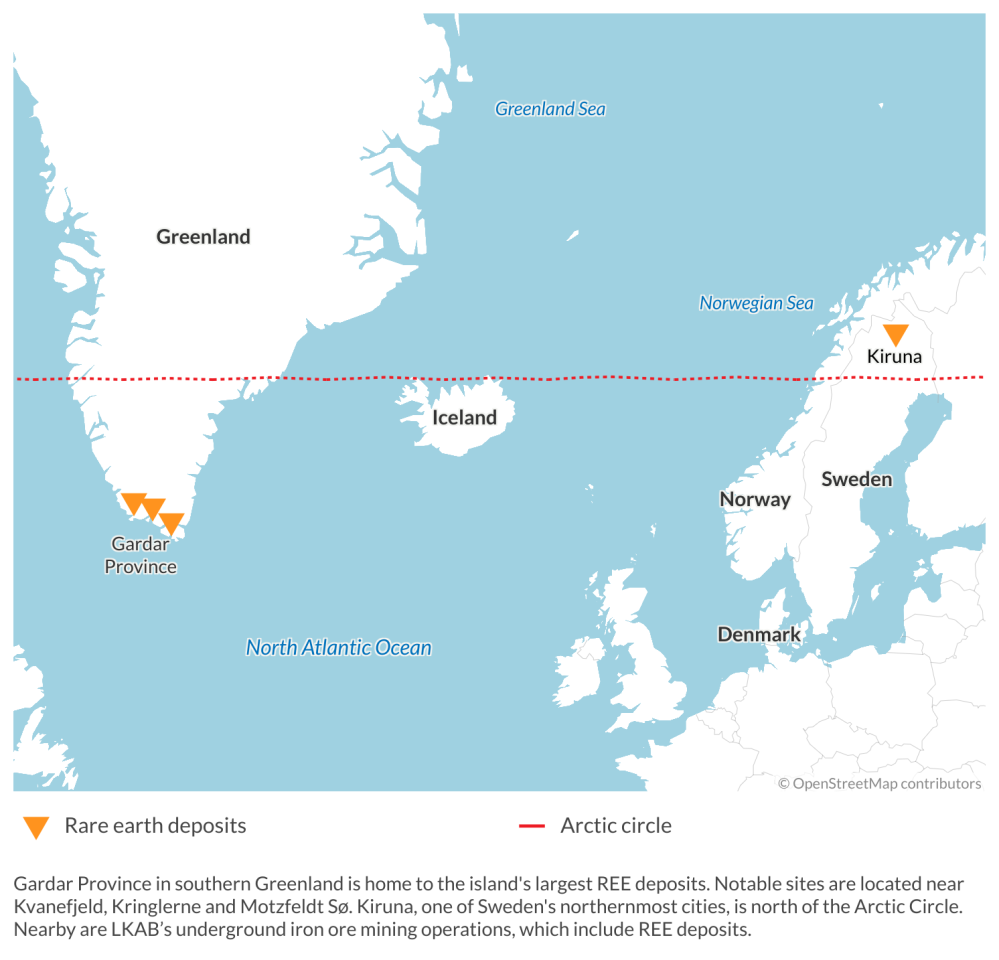

However, there are also large deposits of rare earths outside of China. One of the world’s largest deposits is in the self-ruling Danish territory Greenland. While its land mass contains high levels of sought-after uranium and thorium, reaching them is a problem. Greenland’s government has prohibited uranium mining and the exploration for other metals in rocks with more than 100 parts per million of uranium.

If the EU is to have some degree of autonomy, it must hurry to secure access to deposits of the 17 rare earth elements (REE) and several other metals which the EC classified as “critical” materials in 2011 because of their economic importance and because China’s dominance creates uncertainty. That quest leads to Sweden.

Sweden and rare metals, then and now

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries scientists began to discover rare earth elements. A large number were actually discovered by Swedes. But only recently, with the development of modern technology, have such metals become important.

The first known discovery of rare earth metals was at the end of the 18th century when a black mineral with elements unknown was found in pegmatite in the Ytterby mine outside Vaxholm in the Stockholm archipelago. The world’s likely first mining of rare earth metals in solid rock took place in the mid-19th century in Bergslagen, roughly 200 kilometers west of Stockholm. At this mine, the first light REE, cerium, was discovered and described in 1804.

Today, with industry and transport becoming increasingly electricity-based, and as supercomputing and security systems grow both in complexity and in their use of rare earths, Sweden is looking to build on its REE pedigree as a long-term alternative to China.

The most advanced commercial project is Norra Karr (east of Lake Vattern), where rare earths occur in a nepheline syenite (a plutonic rock similar in appearance to granite). Norra Karr is promising economically, thanks to high concentrations of the most sought-after rare earth metals, and environmentally, due to very low uranium and thorium concentrations. According to Swedish state-owned mining company Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara AB, or LKAB, there are more than 1.3 million tons of rare earth metal oxides in the country’s northern reaches, making it Europe’s largest deposit.

Read more on critical materials:

- The global battery race: Europe’s strategic perspectives

- The energy transition and the risk of resource nationalism

- Critical raw materials: Assessing EU vulnerabilities

- Rare earth minerals return to the U.S. security agenda

But opening a mine is a lengthy process fraught with difficulties. In addition to building infrastructure, social and environmental impact assessments must be completed before permits can be issued; a process that can take 15 years. There are also technical challenges. The REEs in Kiruna are bound in apatite, a phosphorus mineral that occurs in iron ore. To facilitate the extraction process, in November 2022, LKAB acquired the Norwegian company REEtec, which is developing a new method for extracting and separating REEs from substances like apatite.

Accessing the rare earths in Europe has the added dimension of anti-mining initiatives and significant bureaucratic hurdles. The EU needs to streamline approval processes of strategic resource projects required to achieve some independence from China. It is also still uncertain whether LKAB’s REE deposits in Kiruna can actually reduce dependence on China.

Furthermore, mining is only the first step in the supply chain. A new European mine does not reduce supply risks if the EU still depends on processing in China – an economic and military superpower that is neither democratic nor recognized as a market economy by the EU. China’s dominance is primarily in the technologies and facilities needed to transform the raw materials into the sophisticated intermediate products demanded by high-tech manufacturers further downstream.

China’s strategy for rare earths

In recent years, China’s share of global mineral extraction has declined somewhat, but for countries with advanced manufacturing industries, it is not the mineral – what is mined – that is considered most “critical.” What is critical and in demand are the advanced, processed products derived from the raw materials. One example is permanent magnets, which are important components in electric vehicles and wind turbines. Dependence on China is twofold: China dominates both the production of metals and the production of the permanent magnets in which the metals are included.

If the EU diversifies sourcing and is willing to pay for the extraction and processing of rare metals outside of China, it would help create divergent flows of rare metals, lowering supply and security risks.

The reasons for China’s dominance are complex and involve the cooperation of other countries. Mining and processing of metals can be damaging to the environment, socially unacceptable and unprofitable, especially in the short term. But with Chinese Communist Party financial backing, Chinese companies are assured of long-term support in their activities. In the West, high environmental requirements and labor costs result in higher production costs and prices. For many in the West in past decades, it was more profitable to simply import materials from China than build out their own supply chains.

China recognized the potential of REEs early on. In the late 1980s, when the U.S. was still the largest producer of REEs, China’s then leader Deng Xiaoping said: “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.”

REE export limitations

China has been accused of exploiting its control of REEs for geopolitical purposes. During a 2010 territorial dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, China reportedly halted exports of REE oxides to Japan. Beijing denied a ban aimed at Japan, claiming that the change was part of a previously planned reduction in export quotas. The incident spurred Japan to diversify its supply chains, which appears to have succeeded. Between 2010 and 2018, China’s share of Japan’s REE imports decreased from over 80 percent to 58 percent.

More recently, China restricted the export of certain commodities in 2023, citing national security interests. In August, export controls were introduced on gallium and germanium, two raw materials used in the production of semiconductors. In October, permit requirements were introduced to export selected graphite products, with Beijing citing their military importance.

Of specific concern for Sweden, and Europe, is that since 2020 China has stopped issuing permits for the export to Swedish companies of artificial graphite – a material used in the production of battery cells – without explanation. The measure has been viewed as an attempt to inhibit the development of Europe’s fast-growing battery industry, where Sweden is at the forefront.

In November 2023, China introduced stricter export controls for REEs and for the next two years Chinese exporters must report both material type and export destination. According to analysts, China is considering introducing yet more extensive measures to further limit exports of REE-related technology.

Scenarios

In the event of a diplomatic conflict or trade dispute between the EU and China, Beijing could double down on export bans on selected REE products for European companies. An export ban aimed at the entire EU seems unlikely, as it would have serious economic and political consequences for China as well. But a ban for individual countries and sectors within the EU – for example, Sweden and the automotive industry – would be more plausible. This makes Sweden and the future of Europe’s EV industry vulnerable to Chinese export restrictions.

Scenario 1: Legacy supply chains put Europe increasingly at risk

If Europe fails to diversify, which is realistic in the short to medium term due to entrenched European bureaucracy and China’s lead in all stages of the value chain, it puts environmental, climate, economic and security priorities at risk.

In potential crisis situations, for example a Western response with European support to an armed conflict over Taiwan, or Russian influence into Chinese policymaking leading to a deterioration in Sino-European relations, Beijing would be able to cut off European access to rare metals, exerting pressure on EU security policy and imposing an economic cost. This risk would lead to both price and security risks.

Scenario 2: Diversification results in two geoeconomic blocs

If the EU diversifies sourcing and is willing to pay for the extraction and processing of rare metals outside of China, it would help create divergent flows of rare metals, lowering supply and security risks. This not only requires the cooperation of other countries to develop complementary supply chains, but the bloc must develop its capacity for processing and manufacturing, so a larger part of the supply chain is in Europe.

The result could be one raw materials chain for the West and its partners, and another for China and those in its realm, dividing the world into different trading blocs. This would certainly disrupt rest-of-world trade, but looks increasingly likely given other geopolitical signals.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.