Biya to cling to power in Cameroon

Cameroon is bracing for contested elections as the entrenched president tightens control, touts economic growth and takes a hard line on security and political challenges.

In a nutshell

- Biya’s 40-year rule has entrenched the elite and weakened the opposition

- Security crises persist from separatist conflict and extremist violence

- Economic growth continues through mining, services and agriculture

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

When Cameroon’s independence leader Ahmadou Ahidjo decided to step down as president in 1982 after more than 20 years in office, it was an unexpected development. At the time, many independence leaders across Africa had either expressly or implicitly made themselves presidents for life. Except for Leopold Senghor of Senegal, who stepped down in 1980 to make way for his prime minister, such political decisions were extremely rare during the period.

In the previous century, the territory of today’s Cameroon was parceled into German, British and French colonies. The colonies gained independence in 1960 and 1961, at which point the Federal Republic of Cameroon was established. Admittedly, the country’s constitution, like many other African constitutions of the independence era, did not impose term limits on presidential tenures.

In the 65 years since independence, only two men have held the country’s presidency. Cameroon’s upcoming presidential election, set for October 12, is likely to see the incumbent − again − use state security to intimidate the opposition, leading to public protests and harsh security crackdowns. Despite the recurrence of political manipulation, the country’s economy – fueled by services, mining and exports of oil and gas – should remain stable and continue its modest growth trend. The cultivation and export of agricultural products like cocoa and cotton play a crucial role in providing employment.

A fated political decision in Cameroon

The late Ahidjo’s decision in 1982 to transfer power to his long-time prime minister was perhaps the most audacious move of his life, and later, a source of regret. Former Prime Minister Paul Biya has ruled the country as president ever since. A power struggle ensued, Ahidjo’s seemingly unassuming successor outmaneuvered him, and it resulted in Ahidjo going into exile. Beyond Mr. Biya’s political skill, the constitution vests enormous powers in the presidency. Most Francophone states, including Cameroon, copied France’s Fifth Republican Constitution, giving their leaders significant authority.

Over the past four decades, President Biya has entrenched himself with the support of an elite he built around him. Although some constitutional reforms were introduced during the post-Cold War period – as was common in several African countries – Mr. Biya quickly reversed them. Cameroon’s two-term, seven-year presidential limit was expunged from the constitution in 2008 by a National Assembly heavily dominated by his party, the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (RDPC, abbreviation in French).

Facts & figures

Political map of the territory of Cameroon (1901-1972)

The reversal returned the country to a political environment akin to the 1980s, when Mr. Biya had initiated one-party constitutional changes. This time, however, an additional provision was included that granted the president immunity from prosecution after leaving office. This effectively made his actions and omissions as head of state legally unquestionable both during and after his term.

Two months before the 2008 removal of term limits, Cameroonians had protested the regime and demanded President Biya’s resignation. The government’s response was heavy-handed, resulting in about a hundred deaths and thousands of arrests by state security. The regime, undeterred by rising dissent, remained resolute in its efforts to solidify its power by pushing forward with its constitutional amendment.

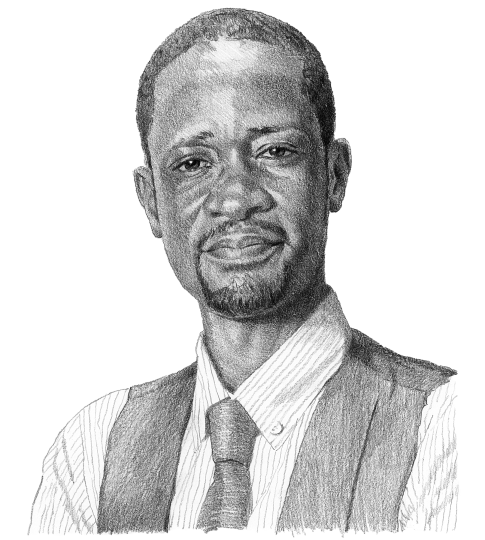

The current decision by 92 year-old President Biya to run for an eighth term after ruling for over 40 years amid heavy criticism and discontent is only a continuation of the regime’s pattern, albeit with some temporary flexibility after the fall of the Berlin Wall. With his candidature confirmed, the physically frail yet still politically strong leader, surrounded by an elite rife with intrigue, is poised to win the next elections, as he has done consistently since the 1980s.

Strategic location, economic progress and security challenges

Located in northwestern Central Africa, Cameroon is a transitional country between West Africa and Central Africa, and between the Atlantic Coast and the geopolitically sensitive Sahel. Its location, combined with shared borders with Nigeria (the continent’s most populous country), Chad (geographically the largest landlocked country in Africa) and by extension the Lake Chad Basin, which it shares with Niger, Nigeria and Chad, makes Cameroon important for the stability of multiple regions.

The Central African Republic, Gabon and mainland Equatorial Guinea also share direct borders with Cameroon. The Equatorial Guinean Island of Bioko, where the capital is located, is closer to Cameroon than to the mainland. Chadian oil is exported through a pipeline that terminates at Cameroon’s port town of Kribi. Domestic developments in Cameroon therefore have significant regional ramifications.

The International Monetary Fund projected a gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 3.6 percent for an economy valued at about $52 billion in 2024. Youth unemployment stood at 6.2 percent during the same year. These figures were underpinned by a growing mining industry and a robust services sector, which accounted for 49.9 percent of GDP.

Cameroon faces major security challenges, the most pressing being armed separatism in the southwest and violent extremism in the north.

Industry contributed 25.6 percent of GDP, with manufacturing making up 13.9 percent. Gold production grew by 20 percent alongside a boost in foreign direct investment (FDI), driven by tax exemptions and relaxed permit processes. The mining sector has vast untapped potential, with experts pointing to promising cobalt reserves, a critical mineral. As of June, inflation stood at 3.2 percent, far lower than Nigeria’s 22.22 percent. Nevertheless, poverty remains widespread with 23 percent of the population living below the international poverty line.

Despite apparent economic progress, Cameroon faces major security challenges, the most pressing being armed separatism in the southwest and violent extremism in the north. The Anglophone separatist crisis highlights the Biya regime’s tendency to respond to dissent with disproportionate force. The government’s crackdown on protests in 2016 and 2017 militarized the separatist movement in the southwest. Since then, separatists have relied on guerrilla tactics against the military, making it one of the government’s biggest national security concerns. A Swiss-mediated peace effort launched in 2019 failed.

The security situation is compounded by ferocious extremist attacks in the country’s northern territory within the Lake Chad Basin. Along with the Sahel, this area is currently considered the epicenter of global terrorism. Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), Boko Haram and other armed groups pose significant threats. Boko Haram has carried out multiple deadly attacks in Cameroon’s far north. In August this year, its operations in Nigeria’s Borno State forced several civilians to flee across the border into Cameroon. While Cameroon’s role in the Lake Chad Basin’s Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) is commendable, it has not ended the threat, and some member states have recently threatened to withdraw.

Cameroon’s elite and political opposition

For more than four decades under Paul Biya’s rule, multiple generations of elites have risen to prominence. From military top brass to boards and management of leading institutions and partially state-owned corporations, these elites remain closely tied to the government.

Consequently, it is rare to find any influential figure in any sector who is not firmly under the regime’s control or pliable to its dictates. As the main beneficiaries of the status quo, they are committed to supporting measures that guarantee its continuity. With RDPC loyalists at the grassroots ready to endorse any decision from the top, the elite is prepared to secure an election victory for the nonagenarian president, who spends extended periods in Europe near his doctors.

That said, Cameroon’s elite is not monolithic. Internal rivalries and competition for power and resources exist between those at the top. This has been evident in recent declarations by some prominent regime allies announcing their candidacy for the presidency in July. Nonetheless, President Biya’s official declaration to run will automatically lead to loyalists rallying around him, as has been the case since he took power more than 40 years ago.

Over 80 candidates have declared their intention to run in the October presidential elections, making the opposition extremely fragmented and weak and paving the way for the Biya-backed elite to more easily secure victory. The ruling RDPC is also well-positioned to re-energize its grassroots, relying on state resources and incumbency advantages.

The disqualification of the most formidable opposition leader Maurice Kamto vividly illustrates the regime’s determination to stay in power by any means possible. Prior to his disqualification, the government had consistently thwarted his rallies, which were attracting large crowds. Opposition candidates cannot rely on state security for protection.

The international dimension

The most recent serious international condemnation of Cameroon’s government came in May following a Cameroonian court handing life imprisonment to Anglophone peace activist Abdul Karim Ali, who was convicted of “hostility against the homeland” and “secession.” Amnesty International denounced the sentence as “deplorable” and called for his release. Apart from this, regional and international actors have largely remained silent on President Biya’s authoritarian entrenchment and the complicity of the elite.

More from geopolitical and security advisor Fidel Amakye Owusu

- Senegal as a strategic player in the Sahel

- M23 rebels defy peace talks, expand control in DRC

- GIS Radio: Unconventional Knowledge. Fidel Owusu on mediating conflicts

The Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), of which Cameroon is a member, has been weakened in recent years by internal crises. The 2023 coup in Gabon and the ongoing conflict in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo caused tensions among member states. In June, Rwanda announced its withdrawal from the bloc, further diminishing ECCAS’s capacity to intervene in Cameroon. Moreover, President Biya is not the only leader extending his rule; Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of Congo, Chad and until recently, Rwanda have all seen entrenched regimes. Thus, ECCAS lacks the moral authority to intervene.

France, Cameroon’s former colonial power, has become more cautious in the region and has withdrawn most of its forces from Africa as successive coups and shifting geopolitics have weakened its influence. Paris is not in a strong position to pressure President Biya. Similarly, the administration of United States President Donald Trump has shown little interest in mounting such pressure. As a result, the only real threat to the regime may come from Cameroon’s mostly youthful population, the majority of whom have known no other leader than the aged president.

Scenarios

Most likely: The regime intimidates opponents, is reelected, quashes protests

President Biya wins the elections with an overwhelming majority, despite his inability to physically campaign at the many rallies organized by the RDPC across the country. The regime will continue using state institutions and security forces to intimidate opponents.

The opposition is expected to reject the results, leading to protests, especially in opposition strongholds and Anglophone regions. The government is more likely to respond with heavy-handed measures, including torture and rushed sentencing, as in the past.

Somewhat likely: Military coup or the regime puts forward another candidate

In 2023, Gabon’s military removed then-President Ali Bongo from power in what was one of the least expected developments, given the country’s history. While Cameroon has never experienced military rule, it is possible that some elements within its military could seize power from the civilian elite if the opportunity or need arises.

Massive protests – or even the threat of them – could also force the regime to make concessions. This might include the reinstatement of Mr. Kamto.

Another possibility is President Biya’s passing before the elections. While this would likely result in another regime member stepping in, it could also spark internal divisions within the RDPC.

Least likely: Opposition unites behind a single candidate to win the presidency

The least likely scenario would be the youthful population massively rallying behind a formidable opposition candidate before the polls and voting to defeat President Biya. This would require both the mobilization of a very large number of people, as well as protecting the ballot against manipulation by the ruling party.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.