China’s success and Eurasia’s future lie in Balochistan

China’s vulnerability to militants and unrest in Pakistan’s southwestern province, Balochistan, threatens its projection of power in Asia and the BRI as a whole.

In a nutshell

- Balochistan is a maritime choke point for Eurasian trade and security

- China struggles to balance security investments with local discontent

- Pakistan’s instability challenges Beijing’s control over the region

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

In 2011, Hillary Clinton, then-United States Secretary of State, declared that the “future of politics will be decided in Asia, not Afghanistan or Iraq.” However, like many in the West, she overlooked a critical point: Afghanistan and Iraq are part of Asia. Power dynamics in the Middle East and its vital waterways in the Arabian Sea are essential to shaping the geopolitics of the world’s largest continent.

Historically, naval strategists have understood this better than diplomats. Portugal and the United Kingdom recognized that controlling Eurasia meant controlling South Asia, and doing so cost-effectively required securing key points in the Arabian Sea. Eurasia’s vast size and terrain have defeated more would-be great powers than armies have. From the west, Napoleon and Hitler were halted by Russia’s harsh winter. From the east, the Mongols faced European forests and Middle Eastern deserts. In the 19th century, the British Empire and Russia clashed in Afghanistan during the “Great Game.”

China, like other aspiring hegemons, must contend with its geography. Its military standoff with India in the Himalayas and its single, easily blocked coastline facing Taiwan and Japan leave it vulnerable to blockades and a two-front war. China cannot attain control of the Eurasian economy without access to the Indian Ocean.

To avoid both scenarios and the geographic entrapment they cause, Beijing must connect its western province of Xinjiang to the Indian Ocean via Pakistan. It is doing so through the development of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a central part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Leading to the deep-water port at Gwadar in Balochistan, the opening of the CPEC to the Arabian Sea provides easy access to Middle Eastern oil, facilitates trade with Europe and Africa and, if the port becomes a fully militarized naval base, may help Beijing in its goal of encircling India in the Indian Ocean.

While the geopolitics surrounding the CPEC reflect a well-crafted Chinese strategy, the situation in Balochistan tells a different story.

Facts & figures

Balochistan and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

Balochistan: China’s Achilles’ heel

Pakistan is a nuclear power that achieved this status with China’s help. However, its internal uncertainty, Islamist factions and Baloch rebel groups, as well as proximity to India and the instability in Iran, make the CPEC as precarious as it is indispensable for Chinese interests. Just as past great powers have encountered challenges in Central Asia, China now faces the perennial issue of managing local threats.

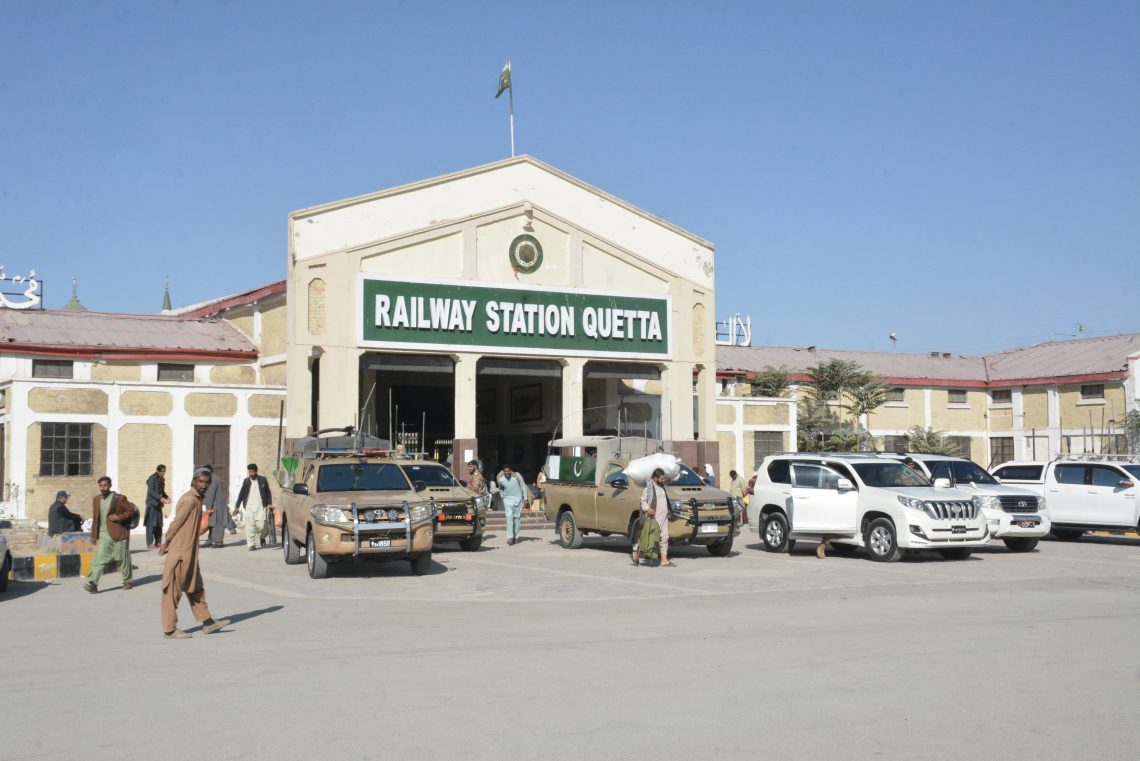

Since 2021, Chinese nationals working on projects along the CPEC have increasingly become targets of attacks by jihadist groups and Baloch rebels. Separatist factions, organized in the Baloch Raaji Aajohi Sangar alliance, include the Baloch Liberation Front, the Baloch Republican Guard, the Baloch Republican Army, the Sindhudesh Revolutionary Army and the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA). These groups have launched a series of assaults against both the Pakistani government and Chinese nationals. The incidents range from suicide bombings and railway attacks to assaults on the Gwadar Port Authority and the storming of the Chinese consulate in Karachi. The attacks highlight both Beijing’s vulnerability in the CPEC and Islamabad’s inability to defend it.

The economic exploitation of Balochistan’s vast resources, combined with severe poverty, systemic neglect by the federal government and exclusion from CPEC projects, drives separatist anger. State repression – including thousands of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings – worsens the cycle of violence, effectively sustaining the insurgency.

Facts & figures

Timeline of Baloch separatism

- 1947: Creation of Pakistan

- 1947: Accession of Balochistan to Pakistan

- 1948,1958-1959, 1963-1969, 1973-1977: Baloch insurgencies against central rule

- 2002: Announcement of the Chinese-funded Gwadar Port

- 2004-present: Start of the fifth, ongoing insurgency

- 2015: Launch of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a flagship BRI project

- 2020s: Rise in attacks on Chinese projects and nationals by Baloch militant factions

Economically, Balochistan’s unrest is taking a toll on Pakistani trade. The Gwadar port, constructed in 2007 and managed by the China Overseas Ports Holding Company since 2013, handled less than 1 percent of Pakistan’s maritime trade in the fiscal year 2022-2023, according to the Ministry of Maritime Affairs. Despite slow growth, the country is working to expand the port, including plans for a ferry line to Gulf Cooperation Council states.

Pakistan’s own geopolitical situation complicates Islamabad’s ability to fully secure Balochistan, as a greater Chinese security presence could alienate the U.S., with whom Pakistan is seeking to build better relations. After a suicide bombing in Karachi last October that claimed the lives of Chinese employees of the Port Qasim Electric Power Company, Islamabad has sought to address Beijing’s security concerns. This has involved enlisting counterterrorism support from China’s intelligence agencies and security firms, as well as allocating an additional $162 million to its military to safeguard Chinese assets and personnel.

In recent months, securing the CPEC has become more complicated due to declarations of independence by Baloch leaders, who have sought support from both India and the U.S. India’s historically ambiguous stance on Balochistan suggests that it does not officially support the region’s separatists, while the U.S. has designated the BLA as a terrorist organization. Against this backdrop, Pakistan faces a challenging situation, caught between its partial reliance on America and the security risks it would encounter if it openly supported the Baloch cause. This also presents a complex dilemma for China.

For Beijing, the question is whether to expand its security presence in a region that is already hostile toward it. Doing so could validate separatist fears about China’s growing encroachment and jeopardize what is arguably the most vital component of the BRI by exposing it to rising insurgent attacks.

The province is a paradox: It is Pakistan’s largest province by land area, but it is also its least populated. Only 5 percent of the land is arable. Yet, Balochistan is the richest in natural resources, containing Pakistan’s largest reserves of natural gas and boasting abundant reserves of coal, copper and other valuable minerals.

The regional economic landscape combines existing industries and employment opportunities in a manner that promotes centralization and resource extraction. These factors contribute to growing economic discontent among the Baloch population, which in turn sustains support for separatism. China’s use of its own workers rather than locals for CPEC projects further aggravates the situation. According to the Pakistan Economic Survey for 2021-2022, approximately 40,000 Chinese workers were engaged in CPEC projects, along with 75,000 Pakistani workers, most of whom are non-Baloch.

Challenges of controlling Balochistan’s Arabian Sea access

Pakistan has long been a state in crisis due to chronic political turmoil, severe economic downturn, substantial military involvement in civilian affairs, a history of coups and security challenges. Regional dynamics worsen Pakistan’s issues, with neighboring Afghanistan once again becoming a hub of jihadist activity after the U.S. withdrawal in 2021. Meanwhile, Iran was rocked by its recent war with Israel and American strikes on its nuclear facilities.

For Balochistan itself, the province has been in conflict with Islamabad since the partition of British India in 1947. Adding to the challenges facing Pakistan’s central government and China as they seek to secure the CPEC, Baloch politics are dominated by tribal dynamics.

In the long run, neither Beijing nor Islamabad is likely to achieve stability in the region. Without significant job creation and the meaningful inclusion of the Baloch population in CPEC projects, which could drive economic growth, or unless extreme measures like population transfer are taken, there appears to be no viable long-term solution.

Balochistan arguably presents China with its first neocolonial challenge. On one hand, Pakistan is an unreliable yet essential proxy state that Beijing needs to circumvent India and maintain sea access in case of a major conflict in the South China Sea. On the other hand, Pakistan’s weakness and Balochistan’s tribal politics create challenges akin to those faced by European colonial powers, likely requiring Beijing to deploy substantial security forces and funding to safeguard its presence.

Externally, the province’s location makes it susceptible to Indian intelligence activities and naval operations in the event of open hostilities in the Himalayas.

More on South Asia

- China’s increasing footprint in South Asia

- India’s multi-alignment and rising geopolitical profile

- Indo-Russo relations amid emerging global realities

There is no certainty about how long and to what degree Pakistan or China will be able to maintain control and sovereignty over the region. While Pakistan’s lack of state capacity is evident, China faces a different challenge related to perception and support. For decades, Beijing has positioned itself as a champion of the developing world. However, the resources it may need to commit to securing the CPEC could undermine this image and portray India as a more favorable ally for these countries. This commitment could lead to discontent within China if Balochistan evolves into a full-fledged insurgency.

Scenarios

Most likely: Balochistan and CPEC overshadow China’s BRI strategy

The most likely scenario facing Beijing in Balochistan is one of increasing security and economic costs. Currently, Pakistan’s government has proven unable to successfully integrate the province into the country in a way that resolves the underlying causes of the insurgency. As a result, China faces the challenge of having to safeguard its own interests within Pakistan as it seeks to mitigate an ethnic conflict.

In Beijing’s case, its usual strategies of Sinification, used within China to forcibly absorb ethnic minorities in provinces like Xinjiang, will not work in Balochistan. The province’s location along the sea means that even if fully colonized by Beijing, it would still depend on infrastructure connecting the Chinese hinterland through Pakistan to access the region.

Additionally, Pakistan has a strong history of Islamist movements and an active insurgency on a scale that China has not experienced since its civil war in the 1940s against the Kuomintang. If the Baloch insurgency deepens and expands, Beijing faces the prospect of costly state-building efforts in Pakistan that go beyond the current projects within the CPEC.

Even if Balochistan’s resistance to Chinese influence does not develop into a fully armed insurgency, it could still potentially gain outside support from one of China’s adversaries and become the largest liability within the BRI. Gwadar and the rail systems connecting it to China are the single-most important infrastructure projects that underpin Beijing’s efforts to access natural resources in Africa and maritime trade with Europe.

Least likely: China pivots to support Baloch independence to safeguard CPEC

Beijing could prevent the growth of Baloch resistance groups by adopting a strategy of economically integrating the population into the CPEC and addressing the root causes of the region’s tensions with Islamabad and its hostility toward foreign nationals. While this strategy may not be effective with Islamist groups, it could help reduce the underlying motivations for a conflict that began before Beijing’s involvement in Pakistan in the early 2000s.

For example, Beijing could emulate its success in transforming Macau into an economic hub by applying similar strategies in Pakistan. China assumed control of Macau in 1999 as a Special Administrative Region under its “One Country, Two Systems” policy. It could replicate aspects of this model by gaining a degree of autonomy over Balochistan from Pakistan through a lease-like agreement. This approach might bring job opportunities and upward mobility for the local population.

Although this strategy could potentially be effective, this scenario is unlikely. First, China’s treatment of foreign workers in other parts of the world suggests that such an approach may not have crossed Beijing’s mind. In Africa, for instance, where China has invested considerable money and effort in securing natural resources, it continues to rely heavily on its own workforce, often at the expense of local populations.

Another factor that obstructs such a Chinese approach is the nature of Baloch society itself. While many groups are secular nationalists, there are jihadist groups operating in the region. Those like Jaysh al-Adl, which operate out of Iran but straddle the Pakistani border, could become a source of resistance to China that Beijing would find more difficult to counter.

Similarly, terror groups like the Islamic State Khorasan Province and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi have also proven hostile to China’s presence. Lacking clear political solutions due to their religious focus, conflicts with such groups could worsen China’s security challenges even if there is an agreement with mainstream Baloch separatists. Combined with the inertia of Chinese foreign policy, Beijing is unlikely to settle Balochistan anytime soon.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.