Fast economic growth in 2021, but not for everybody

Many forecast that 2021 will be characterized by vigorous economic growth. The author takes a more discriminating view and argues that only a few countries, China among them, will be back on track.

In a nutshell

- There is hope for a partial recovery once restrictions ease

- China and India will outperform their Western competitors next year

- In 2021, Europe will only grow by about half of its 2020 losses

The year behind us has been rather problematic worldwide. According to the International Monetary Fund, global gross domestic product (GDP) should contract by 4.4 percent and 5.8 percent in the advanced economies. The figures for Europe and the eurozone are worse: -7.2 percent and -8.3 percent, respectively. Globally, very few countries show signs of growth. One of them is China – its projection shows a 1.9 percent GDP increase.

There is more bad news. In most countries, the public sector is relatively large and its added value has remained more or less constant. This means that the crisis has hit the private sector harder than most statistics reveal. The real postcrisis contraction is closer to 6 percent worldwide and 10 percent in Europe.

There are also some bright spots, however. The data on economic activity between the two Covid waves shows that when restrictions were lifted, most economies were able to bounce back vigorously, albeit not enough to return to their long-term trends.

Partial recovery

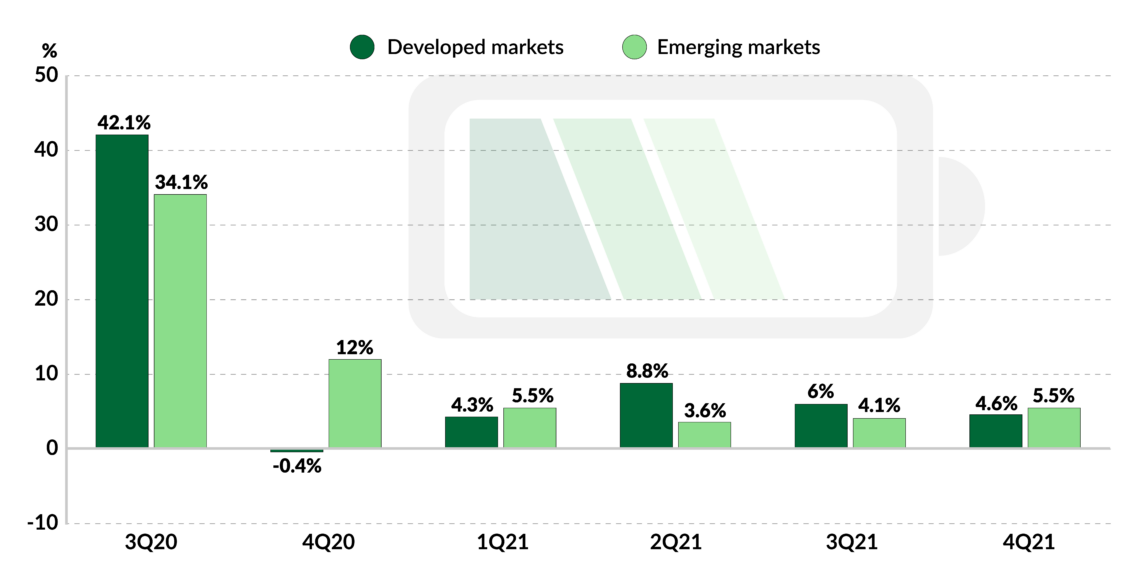

The upshot is that, once Covid-related restrictions ease, there will be hope for a V-shaped, partial recovery. The emphasis on “partial” is crucial. Advanced economies will only grow by about half of their 2020 GDP losses, while world growth might reach about two thirds. Authoritative observers are more optimistic. For example, Morgan Stanley predicts that in 2021, global growth will be faster (6.4 percent) and that the economy will be back on track by the end of the year. China’s and India’s economic growth rates should reach 9.0 percent and 9.8 percent, respectively. Further ahead, the world growth rate should then settle at about 4 percent in 2022, once again led by developing countries – China and India in particular.

The labor market dynamic suggests that East Asia is probably well equipped to bounce back.

The overarching situation is relatively clear, and the vaccination campaigns planned for the first part of 2021 have boosted optimism. But scenarios for 2021 differ when it comes to the possible shape of this recovery. Such forecasts provide insight as to whether and when economic activity will be back to normal. The main issues analyzed in this report concentrate on three areas: the labor market, public finance and monetary policy. These will be examined next and conclusions will be drawn.

Asia’s strength

Employment is problematic mainly in high-income countries. In China, the unemployment rate has been at around 5 percent over the past few years. It hit 6.2 percent in March 2020 and is currently back to normal (slightly above 5 percent). Although Chinese statistics can underreport unemployment, a strong recovery might cause a labor shortage. It is unlikely that the government will be inclined to boost growth just for the sake of creating more jobs. This is why a 9 percent growth rate is an overestimate: the Chinese do not need it.

A similar analysis applies to India, where the unemployment rate was 7.2 percent in January 2020, surged to almost 24 percent in April and fell back to less than 7 percent in the fall. The advanced Western economies present a more troubling picture.

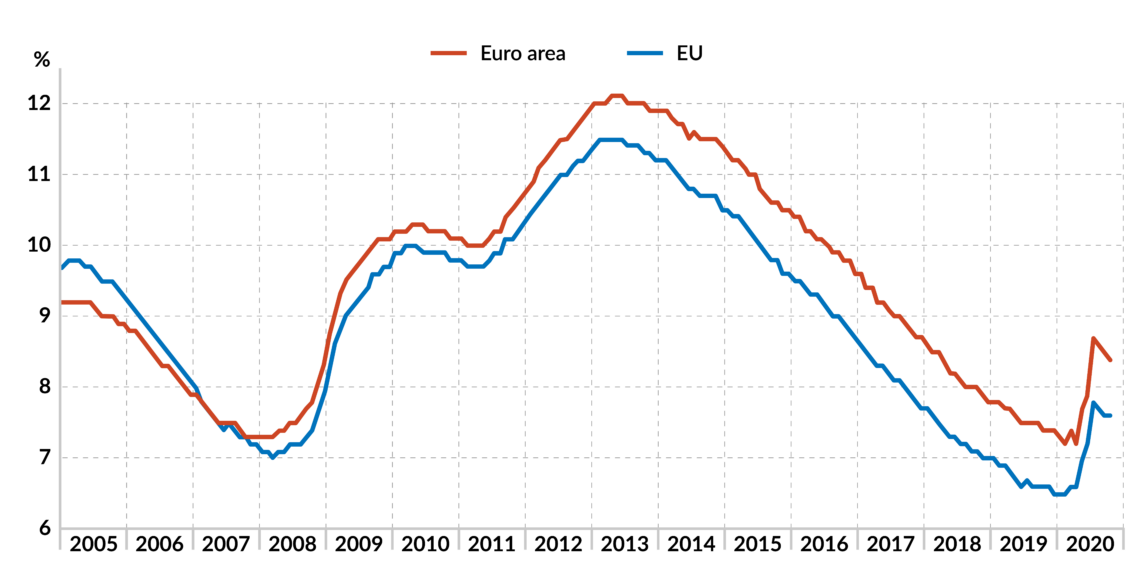

At the end of 2019, unemployment was below 4 percent in the United States and 7.6 percent in the eurozone. It rose to 14.7 percent and 8.8 percent in the spring and summer of 2020. Then, it dropped significantly in the U.S. to 6.7 percent in November 2020, while it stayed high in the eurozone: 8.4 percent in October 2020. (Actually, it might have increased since many Europeans opted to drop out of the labor force after they lost their jobs, lowering unemployment figures.)

To summarize, the labor market dynamic suggests that East Asia is probably well equipped to bounce back and follow more or less the same production patterns as before the pandemic. The prospects for America are far less satisfactory.

Lower grades: Europe and the U.S.

The worst is probably over. However, many individuals stopped looking for jobs and the economic rebound has lost much of its energy in the past few weeks. The U.S. rate of unemployment is unlikely to fall much below 6 percent in 2021. If this proves correct, it would reveal the American economy is less flexible than usually assumed.

This rigidity might intensify if the business world adopts a wait-and-see attitude toward the new administration, which has announced higher taxation and more intrusive regulation. In other words, regardless of what the new government will do, it will take time before the Americans undertake new investments and entrepreneurial ventures.

Facts & figures

Unsurprisingly, Europe receives the lowest grades. A frozen labor market does not necessarily cause slower recovery, although it can. But a highly regulated labor market and an overly generous welfare state make producers think twice before they engage in long-term initiatives. In such an environment, an increasingly large number of potential workers prefer to rely on various forms of subsidy rather than accept a job, especially if it is not on their doorstep.

There are therefore good reasons to be pessimistic about growth in the eurozone in 2021. It will take another year before the region reaches its pre-Covid output volume. At the same time, new labor problems might emerge if the safety nets provided in 2020 are gradually withdrawn.

Public finance quandary

As mentioned earlier, public finance will also play an important role. Decisions in this domain will influence – and be affected by – monetary policy. Public debt in China is currently less than 50 percent of GDP, a tiny fraction of which is owned by foreign creditors. When observing the Chinese economy, public debt is not a critical variable. China’s government relies on loans handed out by the central bank to commercial banks, companies and various agencies, rather than on debt. In 2019, the money supply increased by 8.4 percent, while in 2020, it rose by 10-11 percent.

The U.S. and the eurozone can hardly change their monetary policies without rocking the boat.

In other words, the Chinese authorities did take action during the crisis, but intervention did little to change the financial context and merely kept track of the rising demand for credit. Not surprisingly, interest rates were on the rise.

Of course, this does not mean that the Chinese economy is in perfect health. Many companies and banks remain on the verge of bankruptcy and one has the impression that easy financing and much public investment in infrastructure are driven by the desire to absorb hidden unemployment and keep troubled companies alive. Indeed, Covid-19 has not been a blessing. Yet, the crisis has not seriously undermined China’s economy.

This is one more reason to predict that in 2021 China will vastly outperform its Western competitors. By contrast, the U.S. and the eurozone can hardly change their monetary policies without rocking the boat.

Not much choice

As mentioned earlier, the new U.S. administration will probably engage in even more deficit spending, which will require new debt and encourage the Federal Reserve to refrain from raising interest rates. The recent appointment of Janet Yellen – who presided over a massive Fed balance sheet from 2014 to 2018 – to serve as secretary of the U.S. treasury may support this view. Mutatis mutandis, the European Central Bank will also keep interest rates close to zero.

Of course, the goal is less a matter of encouraging growth than dealing with the legacy of former ECB head Mario Draghi: financing highly indebted governments and ensuring that bad companies and stressed banks stay afloat. In any case, American and European policymakers will not reduce public expenditure to pre-Covid levels, already abnormally inflated.

They will continue diverting resources from the private sector to finance projects run or controlled by government authorities. That is why 2021 growth might be less vibrant than many anticipate.