Scenarios for India’s economy

New Delhi had an ambitious budget plan for the 2020-2021 fiscal year. Now that Covid hit, the government has a third of the Indian economy under lockdown and strives to preserve development momentum.

In a nutshell

- India’s economy faced headwinds before the Covid crisis

- New Delhi has had to shelve its privatization program

- A strong rebound hinges on the pandemic’s quick end

This report is part of a GIS series on the consequences of the COVID-19 coronavirus crisis. It looks beyond the short-term impact of the pandemic, instead examining the strategic geopolitical and economic effects that will inevitably be felt further in the future.

The global pandemic has ruined India’s plans for reviving the flagging economy. The government had to redirect its attention away from declining domestic consumption to deal with a slew of new challenges, including foreign capital flight. However, the significant drop in oil prices will at least give New Delhi financial ammunition to right some of these wrongs. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi plans to press ahead with reforms to regain economic momentum, including a massive privatization scheme, after the COVID-19 pandemic eases.

Pre-pandemic

India faced economic headwinds as it prepared its annual budget, usually presented in early February, at the start of 2020. Domestic consumption, the traditional driver of the country’s economic growth, had fallen for the first time in four decades. A drop in private investment and a slowing world economy shaved an additional one to two percentage points off the expected growth rate. Most gross domestic product (GDP) forecasts at the start of 2020 were in the 5.0-5.5 percent expansion range – acceptable when compared to the global average but way below the level needed to make India a middle-income country. Mr. Modi’s overarching ambition has been to reach this goal.

Another challenge facing Mr. Modi’s budget drafters was the apparent need for more government spending.

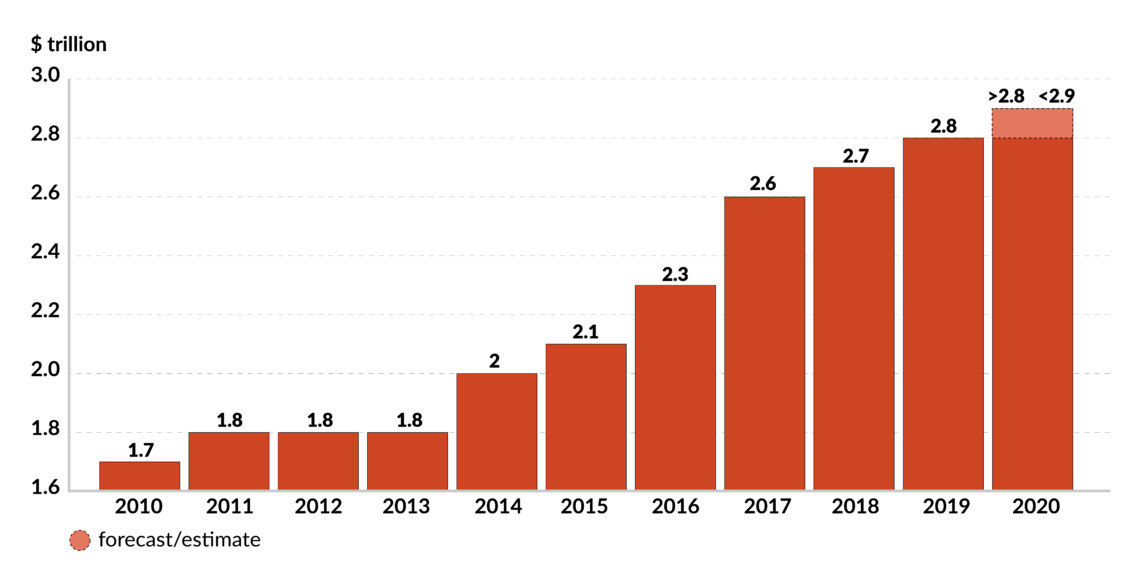

One roadblock was the government’s strapped finances. Falling revenues meant New Delhi would struggle to maintain its fiscal deficit target, set at an ambitious 3.5 percent of GDP. Sticking to this number was critical to keep the momentum of foreign direct investment (FDI). India experienced a record FDI inflow in 2019.

Prime Minister Modi is known for his fiscal prudence. His 2020 budget plan emphasized investment incentives and growth-spurring regulatory changes, not government handouts.

Another challenge facing Mr. Modi’s budget drafters was the apparent need for more government spending. Public investment had to fill a gap in the overall demand left by the private sector. The latter was battered by repeated shocks from the poorly executed demonetization policy, the severe dislocations in the real estate sector and a banking system traumatized by the government’s anticorruption drive, to name just a few. An additional complication was that the prime minister wanted to continue rolling out his signature welfare programs, including those on improving citizens’ access to potable water and universal healthcare. Mr. Modi knew that such policy initiatives had been at the heart of his electoral successes and sturdy personal popularity.

In the end, the government concluded that the best way to square this budgeting circle was through a massive sale of government assets. A privatization scheme targeting some of the large state-controlled companies could bring money to plug the fiscal hole while maintaining public spending and keeping foreign investors happy. As a bonus, the maneuver would restore some luster to Mr. Modi’s credentials as an economic reformer.

The project enthused many in the New Delhi officialdom and – a rare development – won the support of a majority of Indian economists. There was a sense that the green shoots of economic recovery were about to start sprouting.

The viral attack

As the budget was debated in Parliament, coronavirus hit. On March 22, 2020, the Indian government announced a nationwide lockdown. It affected as much as a third of the economy.

Facts & figures

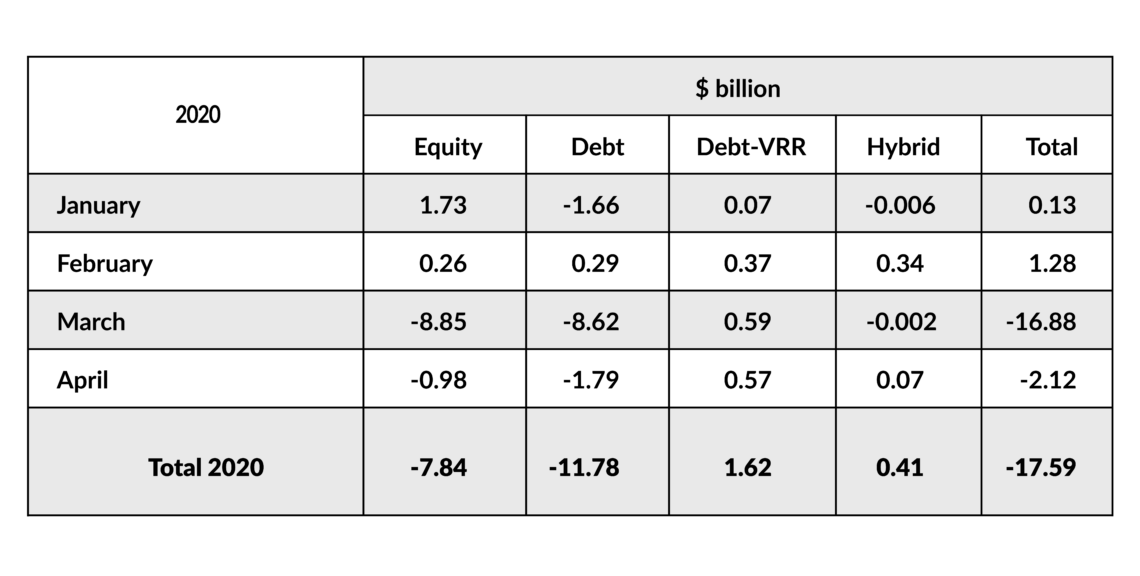

Every economic tracker showed a massive drop in consumer demand with a knock-on effect in the manufacturing and service sectors. Axis Bank estimated the monthly loss of discretionary spending as equal to 1.4 percent of the GDP. Barclays Capital believes each week of lockdown is taking a $26 billion bite out of the economy. Also, there was a significant outflow of foreign capital – some $36 billion fled the stock markets and a quarter of their capitalization evaporated in only one month. The mere announcement of the lockdown led most forecasters to slash 3-4 percent points from India’s expected growth rate. The estimates for 2020 currently vary from the International Monetary Fund’s 1.9 percent to Nomura’s -0.5 percent range.

New Delhi’s economic response to this unprecedented crisis has been similar to those of other governments. A relief package of 1.7 trillion rupees ($13.25 billion) was rolled out, most of it in the form of cash payments to the poorest 150 million citizens (via a newly introduced digital wallet program). Existing welfare programs had their payments frontloaded or increased.

Under another program, businesses and individuals can suspend payments on their loans for three months. There has also been an injection of 3.7 trillion rupees (over $49 billion) of liquidity into the financial system and a sharp interest rate cut by India’s central bank.

The intervention, however, was criticized on two accounts. To some, the measures were insufficient, while others pointed out that much of the money earmarked for them was to come from existing programs and funds. New Delhi hints that another industry-specific bailout was planned for after the lockdown.

If oil prices remained in the $25 per barrel range, the Indian government would realize a huge financial benefit.

All of this has inevitably rendered the government’s original economic plan moot. The fiscal deficit can grow an additional 0.5 percent of GDP – but past that point, it would push up against the legal limit. Making up for the lost ground would require a restoration of consumer confidence at home and an introduction of more alluring incentive schemes for foreign investors.

The crude savior

If coronavirus is a black swan event for the economy, the white knight may prove to be the collapse in crude oil prices. India is the world’s second-biggest oil buyer and the bill for these imports is one of the two largest it foots every year. With prices near $20 per barrel – the lowest level in the last 20 years – the country stands to save $30 billion in the fiscal year 2021, assuming no significant uptick in global demand.

The central and state governments pile so many taxes on oil sales that, at the pump, Indian consumers pay an equivalent of $150 per barrel for this commodity. When oil prices softened in the past, customers hardly benefited: the governments usually pocketed the difference. The Modi government has raised excise surcharges on gasoline and diesel fuel even as the crude prices have crashed, signaling the path it would take.

If oil prices remained in the $25 per barrel range over the coming months, the Indian government would realize a huge financial benefit, potentially defraying some of the costs inflicted by the pandemic. Weighing the pros and cons of an oil price drop, investment bank JP Morgan Chase has calculated that each $20 fall in the price adds between 0.4 to 0.5 percentage points to India’s GDP growth.

In the long run, a commitment to deeper structural reforms could boost confidence among foreign investors. Prime Minister Modi has already assembled several task forces to see how the pandemic can be used to India’s advantage. The most ambitious plans revolve around wooing foreign electronic and other manufacturing firms fleeing from China. Other expert groups are looking at privatization schemes, labor reforms and accelerating infrastructure spending.

Scenarios

As long as the pandemic’s trajectory remains uncertain, predictions on the scope of the economic damage it will inflict must be hedged.

The worst-case scenario for India posits that the economic disruption would continue until the first quarter of 2021. This would press supply and demand into a vicious downward circle and almost certainly tip the economy’s growth into negative territory. With the rest of the world presumably finding itself in no better shape, there would be no external lifeline. Under such conditions, Prime Minister Modi would be forced to jettison all of his ingrained fiscal probity and pile on government debt to try to keep the economy from prolonged depression. India’s investment-grade rating could suffer, driving away conservative foreign institutional investors like the pension funds.

The consequences for India would be severe for several years: a swollen public debt, constrained private sector and reduced growth potential.

The most likely scenario, however, assumes the health crisis will ease by June. If this proves the case, India could expect a modest GDP growth rate in the 1-2 percent range. The government would need to stretch its fiscal operation, but the oil dividend would make the task easier. However, privatization plans would be shelved until markets become propitious. The year 2020 would not advance India toward its goal to become a medium-income country. However, its ability to retain a better-than-average economic growth would likely entice a return of foreign capital flows by early 2021.

The last, most optimistic script assumes the pandemic will end as suddenly as it started. The Indian economy, thanks to pent-up demand and a reservoir of liquidity, would roar back to life. Combine this with an oil windfall and a decision to press ahead with reforms, and a positive macroeconomic environment emerges complete with large government spending, good investment opportunities, low taxes and low interest rates. Foreign capital, thanks to the stimuli pumped out by the world’s central banks, would begin to return to India as early as the third quarter of 2020. Achieving a 4-5 percent growth rate would be conceivable under these conditions. The IMF surprised many by saying India could rebound to 7.4 percent growth next year. Admittedly, this scenario is not very likely, as it requires some lucky breaks and quick and pragmatic policy responses, not only from New Delhi but other capitals as well.