Geopolitical wrangling over Iran’s nuclear program

Iran has demonstrated grit and determination in mastering nuclear technology. The time it would now need to build atomic weapons may be too short for the West’s comfort.

In a nutshell

- Iran’s nuclear weapon “breakout time” is short

- A nuclear-capable Tehran could further disrupt the Middle East

- Iran might still cautiously refrain from taking such a consequential step

From its belligerence in the Persian Gulf, to its support of Russia against Ukraine and its sponsorship of terrorist organizations like Hamas and Hezbollah, the Islamic Republic of Iran has posed never-ending challenges to international security. But the issue that generates the most profound anxiety in the West is its nuclear program. While its goals, officially geared toward civilian energy production, remain somewhat debatable, it is generally agreed in Western security circles that Tehran has been mastering nuclear technology to be capable of building atomic weapons should it want them.

That leads to two highly pertinent questions: will Iran move to acquire a nuclear military capability or ultimately refrain from doing so, and what would be the consequences of each decision?

Nuclear know-how

Iran has been involved in both covert and overt nuclear efforts for decades. While concern over the program goes back to the 1990s, when Russia pressed ahead with the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant for Iran, worries became significantly heightened in the early 2000s.

At that time, evidence emerged that Iran was engaging in undeclared nuclear activities and was suspected of violating its obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which Tehran ratified in 1970.

The NPT seeks to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and technology beyond the five original nuclear powers while allowing for civilian nuclear programs for peaceful pursuits and establishing confidence-building monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

While Iran has long insisted that its nuclear program is for peaceful electricity generation purposes, its undeclared involvement in uranium enrichment has been of particular concern. This process can be purposed for both the production of low-enriched uranium (LEU) and highly enriched uranium (HEU).

Facts & figures

Factbox: Enriched uranium

Uranium is one of the most common elements in the Earth’s crust. Enriched uranium is made by enhancing naturally occurring uranium. Enrichment increases the concentration of uranium U-235 atoms that can be used to produce energy.

Natural uranium deposits contain about 0.7% of the U-235 isotope. Low-enriched uranium, or LEU, has enrichment levels up to nominally 4.95%. LEU is suitable to make fuel for a typical light-water reactor, the most widely used reactor type for nuclear power generation worldwide.

Highly enriched uranium (HEU) has a 20% or higher concentration of U-235. The weapons-grade variety usually contains 85% or more of the U-235 isotope. The first uranium bomb, used by the U.S. in 1945, contained 64 kilograms of 80% enriched U-235.

Trying to persuade Tehran to stop

In an effort to stem the expansion of the Iranian nuclear program, a multilateral international agreement known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was reached with Iran in 2015, involving the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, the European Union, China and Russia.

Iran no longer considered itself bound by the JCPOA. In mid-2019, the IAEA stated that Iran had breached the agreement.

In exchange for limiting its nuclear program and allowing additional international monitoring and verification, Iran would receive several benefits, including the release of foreign-held financial assets that had been frozen and relief from some, but not all, punitive economic sanctions.

The JCPOA assumed that, based on the restrictions in the agreement, it would take Iran at least a year to accumulate the necessary fissile material for a nuclear warhead, providing sufficient time to detect Tehran’s intentions to militarize its program and then intervene to prevent it.

Red more on Iran’s stakeholders

Iran’s decision makers

Examining Iran’s strengths and weaknesses

In 2018, during the administration of President Donald Trump (2017-2021), due to perceived shortcomings in the JCPOA including the “sunsetting” of critical provisions, verification and compliance issues, and the absence of restrictions on ballistic missiles, the U.S. withdrew from the agreement.

As a result, Iran no longer considered itself bound by the JCPOA. In mid-2019, the IAEA stated that Iran had breached the agreement.

Under President Joe Biden, who took office in January 2021, the U.S. pledged to negotiate with Iran for a “longer and stronger” JCPOA-like agreement that would deal with the “deeply problematic issues” of its predecessor. However, to date, the negotiations conducted in Vienna have failed to revive the 2015 accord or conclude a new agreement.

Whether as a signal of intent or a negotiating strategy, Iran has violated various limits specified in the JCPOA, significantly advancing its nuclear program and causing alarm in international political and security policy circles.

According to the IAEA, which monitors and reports on Tehran’s nuclear program, Iran’s stockpile of uranium enriched up to 60 percent purity in its underground facility in Fordow has continued to grow. An October 2023 report by the non-partisan U.S. Congressional Research Service lists additional compliance problems, including the number, type and locations of centrifuges used for uranium enrichment and uranium metal manufacturing that could be used in the assembly of a warhead.

If those assessments are accurate, Iran can produce more uranium to higher levels of concentration more quickly than it was previously able to do.

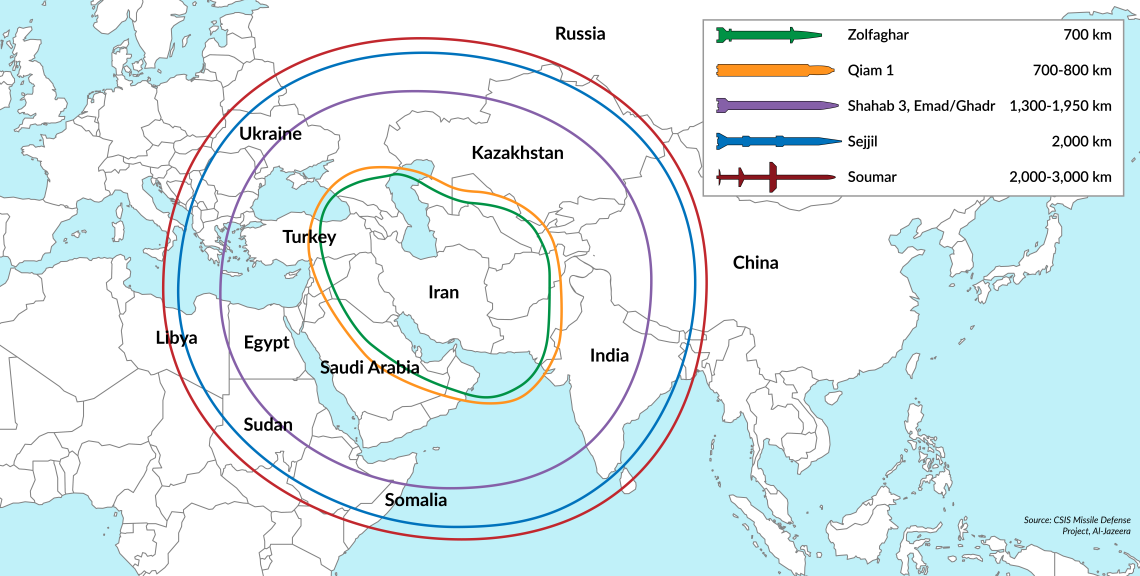

Iran has been making significant strides in developing a strategic ballistic missile. It already fields the largest conventional missile arsenal in the Middle East.

As a result, the “breakout time” – the time Iran needs to manufacture the necessary weapons-grade uranium required for assembling a single nuclear weapon – is significantly shorter than conceptualized under the JCPOA.

The IAEA now asserts that Iran has enough enriched uranium for several bombs if it decides today to build them. The U.S. Congressional report estimates that Iran is now capable of enriching uranium to weapons-grade in a matter of one to several weeks.

The delivery systems

A country needs a delivery system to make a nuclear weapon militarily significant: a missile or bomber to carry the atomic explosive to its target.

Many believe that Iran has been making significant strides in developing a nuclear-capable ballistic missile. It already fields the largest conventional missile arsenal in the Middle East, capable of covering the entire region, parts of southern Europe and Russia, and even western China. In 2023, Iran boasted of having added the hypersonic missile Fattah to its force.

Iran’s ballistic missiles

Tehran is also assumed to be working on long-range ballistic missiles under the guise of a civilian space program currently used for launching satellites. Notably, the technology used in a civilian space launch vehicle is remarkably similar to that used in an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM).

The warhead challenge

The last looming question is whether Iran can build a nuclear warhead to pair with a delivery vehicle; this remains unclear. On the one hand, it lacks an under- or above-ground nuclear test to assist warhead development and prove its engineering concept. Though risky, on the other hand, simulations on the latest-generation supercomputers may render such testing potentially unnecessary.

Iran eventually will decide if it wants to become a nuclear power or not. The decision is going to have far-reaching consequences.

If Iran has a functional warhead design, the current assessment is that it would need up to one year to assemble a test-ready or (potentially less reliable) deployable nuclear weapon, assuming it has amassed the necessary fissile material.

The development and deployment of a nuclear weapon is a singular scientific and engineering undertaking. But Iran is apparently acquiring the know-how, experience and materials needed to accomplish it.

Scenarios

Iran eventually will decide if it wants to become a nuclear power or not. The decision is going to have far-reaching consequences.

Less likely: No nuclear breakout

Despite well-grounded concerns about the direction and final objective of Iran’s program, Tehran may, in the end, opt not to join the nine generally understood nuclear states. Presently, five countries are designated as such under the NPT and eight have publicly announced having detonated atomic devices.

Iran could decide to limit its nuclear program to the production of LEU to feed its current and future nuclear reactors, eliminating the need to import it from abroad, for example, from Russia.

Considering the country’s oil and natural gas wealth, that may seem an expensive strategy. However, domestic LEU production would free Iran to export more fossil fuels, bolstering government revenue and the economy while relying more on nuclear power for its electricity consumption.

Also, continuing its nuclear program as a civilian rather than a clandestine, military-purposed activity could allow Iran to improve its relations with the international community.

Realistically, however, due to the authoritarian nature of the Shia regime, its perceived ambitions in the Muslim world and its enmity toward its Sunni neighbors, the U.S., Israel and the West generally, this scenario is not very likely – barring a radical regime change in Iran.

More likely: Nuclear breakout

While it could merely be a pressure tactic to create a positional advantage in negotiations over a JCPOA follow-on agreement, the trajectory of Iran’s nuclear program is alarming.

Tehran is within striking distance of deploying a nuclear weapon, likely within a year, should it decide to do so. Outside assistance from a foreign country (such as North Korea, Russia or China) or a foreign entity could shorten that timeline.

Deploying a nuclear weapon would make Iran the first Muslim country in the Middle East with the bomb and one of two Muslim countries in the world with one, the other being Pakistan. Such an accomplishment would confer significant (if ill-gotten) prestige and status on Iran.

A nuclear arsenal would give Tehran greater freedom of action internationally, outsize the conventional military deterrence of its neighbors and deter the threats it perceives from Israel and the U.S.

It should be expected that this would cause significant instability in the Middle East, stoking an arms race and the possibility of further nuclear proliferation in the region, including by two regional powers, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

Military action against Iran’s nuclear program is certainly a possibility at some point before Iran builds a bomb. Such a strike would create shock waves across the region and around the world and cause turbulence in energy markets. While Iran’s nuclear program could prove limited to peaceful electricity generation, Tehran’s grand geopolitical ambition, its regional rivalries, expanding nuclear infrastructure and ballistic missile programs and international adventurism regrettably point to an altogether different story. Consequently, this scenario is the most likely of the two presented.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.