Could Italy look to China for financial rescue?

Italy’s trade and investment links with China remain limited, but the financially strapped EU country could offer strategic assets that are of great interest to Beijing.

In a nutshell

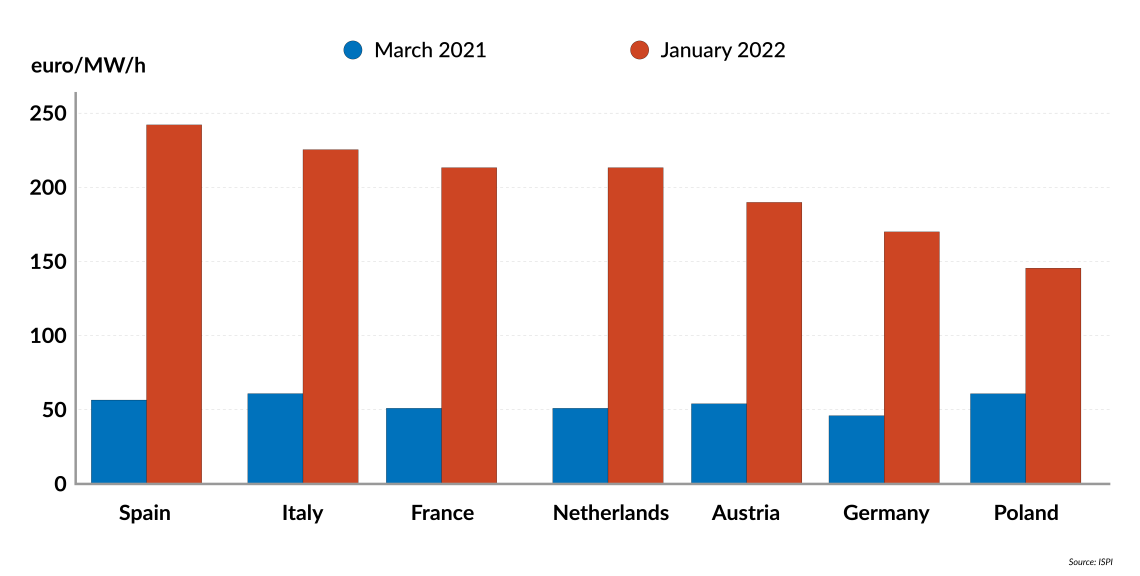

- The energy crisis and financial tightening threaten to destabilize Italy

- The country’s political class has failed to address economic and financial woes

- If the EU refuses to bail out Italy again, Rome may turn to China for help

Historically, Russian leaders repeatedly singled out Italy as the “soft belly” of the Western bloc. Russian President Vladimir Putin continues this approach, and his choice is not entirely unjustified. For example, Italy’s financial and military support for Ukraine has been modest, while the pro-Russian mood of Italian public opinion runs relatively high. Also, Italy moved to tighten its links with China; the economic fruits have been small thus far, but there is a rescue scenario here that the European Union should start worrying about.

The center-right coalition dominated by Ms. Giorgia Meloni has won the latest elections. Matteo Salvini, the leader of the Lega party, and Mario Berlusconi of Forza Italia are parts of that coalition. They have both aired proposals to lift the sanctions on Russia and explore options for a soft agreement with the Kremlin over Ukraine. Moreover, the Italian economy is fragile: its gross domestic product (GDP) has been stagnant since 2008, productivity has failed to rise for the past 25 years, and its public debt is above 150 percent of GDP (the EU average is 88 percent).

Vulnerable Italy

The upshot is that Italians are restless: increasing taxation has de facto cut households’ incomes, while inflation is taking a heavy toll on fixed-income earners and pensioners. The energy crunch and the financial context do not bode well, either. Italian companies are highly dependent on gas and debt. Thus, they are particularly vulnerable to the winter energy crunch and the increasingly hawkish mood now prevailing in Frankfurt. Many companies will be shutting down during the next few months. As a result, public expenditure and unemployment will rise.

Facts & figures

Electricity prices in Europe

Italy’s current strategic vision is also uncertain. In early 2019, the government led by then-Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte and his deputy Luigi Di Maio announced Italy would strengthen its ties with Beijing; soon after, both welcomed a huge Chinese delegation to Rome. Despite criticism from the rest of the European Union and the United States, Mr. Conte’s government opened Italy to Beijing’s Belt and Road initiatives and engaged in efforts to attract Chinese foreign investments to Italy.

Although the commercial ties between China and Italy will remain strong, we posit that finance is key.

At the end of 2019, the Chinese presence in the Italian financial and energy industries was significant. About half of the companies involved were in Lombardy, the heart of the Italian economy. Things changed when Mario Draghi replaced Mr. Conte. Indeed, during the past two years, Mr. Draghi has made it clear that even though China was an important partner, Italy’s economic interests remained firmly anchored in the West. As a result, the government blocked several key acquisitions proposed by Beijing and the Italian fascination with Chinese investments cooled off. The way China dealt with Covid did the rest.

Barriers to growth

Mario Draghi remains influential in Italian politics, but he is not likely to play a role in future governments. It is hard to say which way the new government will go regarding China. Although the commercial ties between China and Italy will remain strong, we posit that finance is key. Three main overlapping areas will provide the economic playing field.

As mentioned above, one area is foreign direct investments, which Italy badly needs for at least two reasons. Overall investments in Italy are low: Italians are hesitant to engage in new entrepreneurial activities in their own country, and investors in other Western countries have other priorities. This is understandable. The Italian market is stagnant, and its economic environment – the quality of the labor force, taxation, regulations, bureaucracy and judiciary system – is not perceived as encouraging. Yet, investments are the critical ingredient for growth: large endowments of machinery enhance labor productivity and are the vehicle through which new technologies are transferred to production.

The second reason regards industrial organization. On average, Italian companies are unusually small. That may be advantageous when operating in market niches and contexts that require quick decision-making and flexibility. However, small companies find it challenging to finance research, absorb new technologies, take advantage of opportunities in global markets or manage the transition from one generation to the next. In this light, Chinese partners could open new venues for Italian exports, help increase their size and offer Italian firms better opportunities for obtaining low-cost semi-manufactured goods.

Limited mutual interest

Despite such prospects, the data shows that Italians are not too eager to invest in China, and the Chinese do not care much about producing in Italy. Thus far, Italians have bought or realized production capacity in China for only 11.5 billion euros, while the Chinese figure is 1.0 billion (2020 data).

These figures are unlikely to change much shortly, regardless of the potential geopolitical scenarios. There has been considerable unwarranted noise in this area; investment inflows and outflows have indeed been significant, but so have been disinvestments.

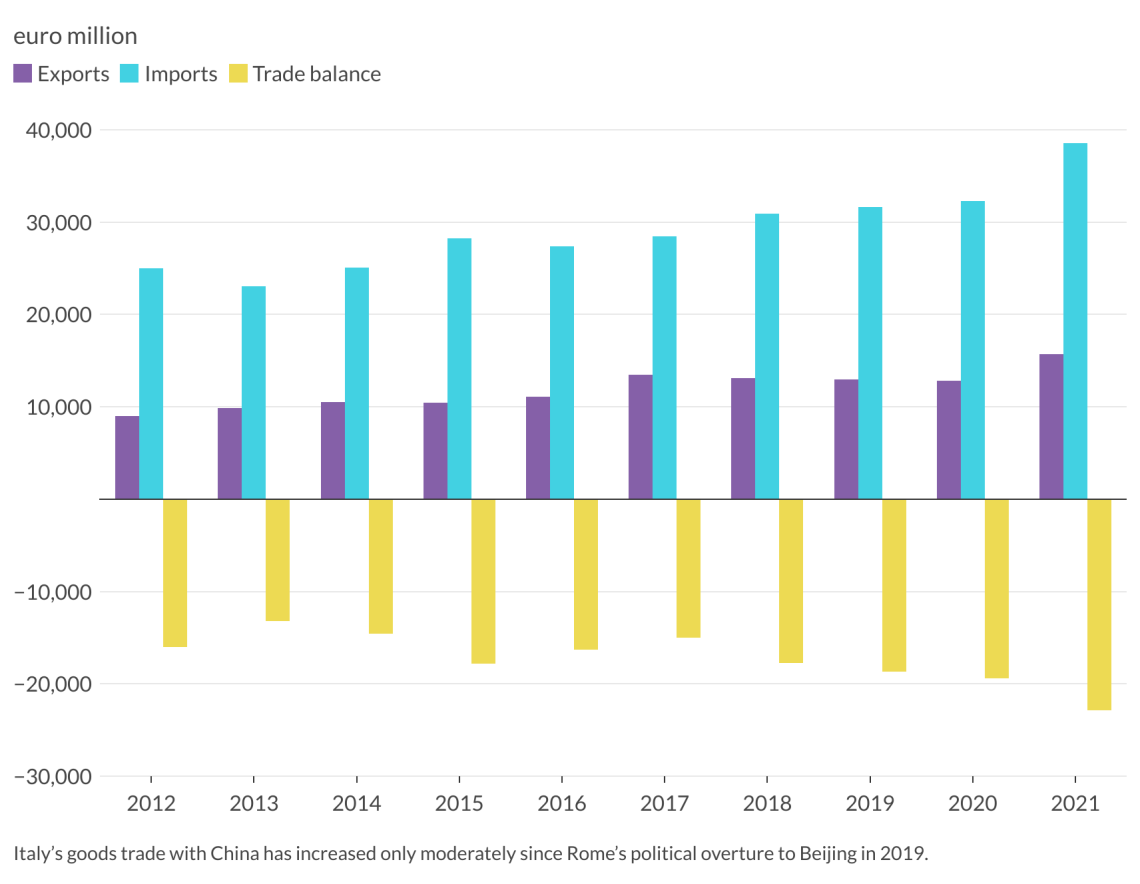

The size of trade flows partially confirms the picture sketched above. Although the value of Chinese exports to Italy has risen in the past three years, China (excluding Hong Kong) is sending only about 1.3 percent of its total exports to Italy. The figures for the U.S. and Germany are, respectively, 17.1 percent and 3.4 percent.

Facts & figures

Likewise, China receives only 1.1 percent of its total imports from Italy. In a nutshell, Italy is not a significant trade partner for Beijing. By contrast, even if China receives only 3 percent of the total Italian exports, it is Italy’s fourth-largest supplier (the figure is 8.3 percent for Italy’s imports).

These supplies are relatively diversified; the top two items are cell phones and computers. Once again, Italy is vulnerable to international economic crises, but China would hardly be one of its top direct concerns.

A lifeline from China?

The third area of interest is public finance. As mentioned earlier, the Italian public debt is out of control, and the cost of debt servicing in 2022 will be about 100 billion euros (about 5.5 percent of GDP). The country would already be bankrupt if the European Central Bank had not intervened and bought massive quantities of Italian treasuries at a rather high price. Italy would default if the European authorities stopped financing its public debt.

China could offer Italy much-needed financial help, or Italy could ‘persuade’ Western governments to come to its financial rescue once again – thus preventing China from playing the white knight.

The cost of debt servicing is indeed threatening. Opposition to blind acceptance of Italian profligacy is quietly mounting in Brussels and Frankfurt. Markets seem less and less eager to buy Italian bonds: their inflation-adjusted yield is deeply negative, and the country’s growth outlook does not suggest that things will improve. Italy’s political situation, too, is confusing, to say the least.

Within this context, China could offer Italy much-needed financial help, or Italy could “persuade” Western governments to come to its financial rescue once again – thus preventing China from playing the white knight. Of course, Beijing would not do it for free.

Scenarios

The EU had better prepare

The figures show that the Chinese interest in establishing significant production capacity in Italy is limited. Instead, they buy shares in potentially profitable businesses and select high-tech niches. However, China has repeatedly displayed a strong interest in having a foothold on the Italian Adriatic coast, particularly in Trieste. That might be the price the Italians need to pay to persuade China to fund their public-finance profligacy.

To summarize, although the current economic ties between China and Italy are far from negligible, they remain modest for both sides. That does not mean that international tensions would not produce repercussions. For example, supply problems between China and the U.S., Germany and France would affect Italy too.

Nonetheless, one should not overestimate the direct impact of the Chinese crisis on the Italian economy. That is good news. The bad news is that Italy is in poor shape. Its political elites are unlikely to engage in what it takes to begin fixing its major problems and might soon look for external help. Will Brussels and Frankfurt oblige once again?

China has the resources and the strategic vision to extend a helping (if predatory) hand. Italian leaders might quietly give in. Mr. Putin may have dug himself into a deep hole in Ukraine, yet Western leaders had better decide how to deal with Italy if the economic situation continues to deteriorate.