Central Asia’s Middle Corridor gains traction at Russia’s expense

Nations in the southern Caucasus and Central Asia have been quick to take advantage of Russia’s problems and expand their alternative China-Europe freight route.

In a nutshell

- Shipping cargo between Europe and China through Russia has become problematic

- The shorter route through Central Asia is attracting new interest

- The U.S. and EU are increasing support for the Middle Corridor

Among the many significant geopolitical consequences of Russia’s war against Ukraine has been the boost in regional integration along the “Middle Corridor” – a fast-developing land and sea freight route from Europe to China that aims to become a viable alternative to the long-established northern route through Russia.

That development is likely to continue receiving increased support from the European Union and the United States, engagement from Turkey and, eventually, meet reluctant acceptance by Russia, China and Iran.

Facts & figures

The Middle Corridor

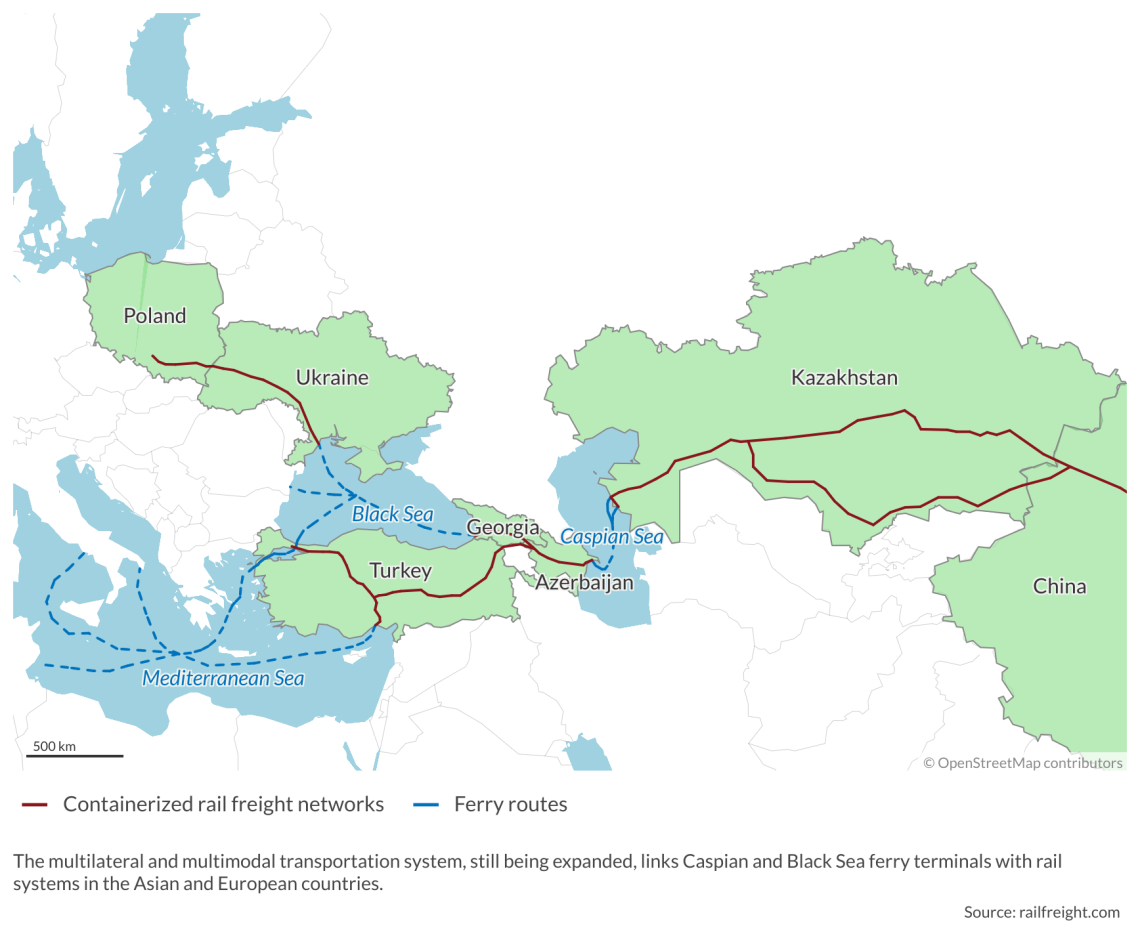

The Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), known as the Middle Corridor, is a rail freight and ferry system linking China with Europe. It starts from Southeast Asia and China, and runs through Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey before reaching southern or Central Europe, depending on the cargo destination. Geographically, this is the shortest route between Western China and Europe. On March 31, 2022, the governments of Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan and Turkey signed a declaration on improving the transportation potential through the region.

The freight route across Russia, which for decades served as the main overland link between Europe and China, has become problematic as Beijing and other countries try to shield their economies from the snags caused by the sanctions on Moscow.

Past obstacles

Until recently, obstacles to regional integration across the heart of the ancient Silk Road looked overwhelming. The post-Soviet space’s many issues bedeviled cooperation, including the ongoing conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the occupation of Georgian territory by Russia and the collapse of the government in Afghanistan after the hasty U.S. withdrawal. Also, the continued antagonism of the West with Russia, China, and Iran led to the long-held perception of the area as featuring elevated strategic risk and uncertainty.

China’s effort to develop a freight corridor through the middle of the region as part of the vast Belt and Road network met with mixed results. Many regional partners became skeptical of joint projects with Beijing, having witnessed the limited success of the Pakistan-China Economic Corridor and having grown distrustful of Beijing’s intentions. The Chinese tended to control and dominate the construction, often using their own workforce and materials.

Facts & figures

One significant project that matured despite the many concerns over regional stability was the Southern Gas Corridor, linking gas fields in Azerbaijan with a pipeline across the Caspian Sea to Georgia, Turkey and across the Mediterranean to Italy. This project proceeded despite regional challenges, as well as opposition from Germany and Russian efforts to thwart the initiative by funding environmental and political groups to bring challenges against it. The final leg of the system is now operational, in part thanks to U.S. lobbying of Italy.

In addition to the pipeline, regional logistics hubs continue to develop. The projects include the modernization of the port in the Georgian city of Poti and the redevelopment of the port of Baku in Azerbaijan.

The war’s aftermath

In the wake of the Western sanctions on Russia and Europe’s expanded effort to improve energy security by diversifying sources, the EU signed a deal in July 2022 to obtain gas via the Southern Gas Corridor. Though the volume is a fraction of the amount needed to replace Russian gas supplies, the deal is considered strategically important.

The Southern Gas Corridor has renewed the West’s interest in the Caucasus and Central Asia as potential energy sources, part of global transport and logistics, and manufacturing and trade partnerships in the longer run. Other factors have changed the state of play, including Azerbaijan’s success in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War.

While raising regional tensions, Russia’s protracted war in Ukraine also exposes the reality that win, lose or draw, it will take Russia years to rearm and upgrade before it could contemplate further significant expansion in the post-Soviet space.

Read more on regional players:

Turkey has the right to protect its national interests

New realities in the South Caucasus

At the same time, a new nuclear deal with Iran looks increasingly unlikely. If the regime in Tehran remains under significant sanctions, it will be less likely to interfere with its northern neighbors.

China seems less engaged in the Caucasus and Southern Europe as Beijing focuses on expanding its opportunities in Latin America and Africa.

Space for independence

Altogether, these developments leave more geopolitical space for countries in the Caucasus and Southern Europe to chart more independent policies. Their interest in engagement with the U.S., Europe and, to some extent, South Korea and Japan, is growing.

Japan, for example, has tested the Middle Corridor’s freight potential by shipping goods to ports in China, transporting them by rail across Central Asia to Azerbaijan and shipping them over the Caspian Sea to Europe. The U.S. is considering a regional hub with its International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) in Tbilisi, Georgia.

Aside from Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan appears the most forward-leaning country in Central Asia, seeing the Middle Corridor as a strategic advantage and an opportunity to expand its role in energy, logistics and manufacturing.

Azerbaijan also sees the corridor’s strategic importance and prioritizes regional integration.

Turkey has been a significant investor and supporter of regional efforts. It revitalized the Turkic Council, which includes Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey and Uzbekistan.

Good prospects

Energy will be a significant driver as Europe seeks to diversify energy resources.

Turkey will likely play an increasingly important regional role. In addition to its current bilateral efforts, Ankara may well seek to develop closer ties with Georgia, a strategically important country for connectivity along the Middle Corridor. With its prospects for NATO and EU memberships looking less likely in the near term, Georgia may turn to Turkey for the security guarantees and economic engagement it currently lacks.

While the prospects for an east-west transport corridor are looking more promising, the north-south avenue (Russia through the Caucasus to Iran) has become increasingly less feasible due to Russia’s and Iran’s continued political and economic isolation.

The east-west corridor has progressed through public-private investments and management, mainly without Chinese funds and influence. However, obstacles remain, such as unresolved customs and border controls or data management matters. Another big problem is the lack of modernized infrastructure. These issues thwart efficient integration, making the east-west freight route less economically competitive than the northern corridor across Russia or southern maritime routes. Nevertheless, the global demand for transport amid supply chain disruptions makes the Middle Corridor attractive as an alternative means to get some goods to market.

As a result, the route will continue to develop. However, a dramatic downturn in demand due to a global economic slowdown would negatively impact future efforts.

Facts & figures

Factbox: The Middle Corridor (TITR) in 2022

- Cargo transshipment through Central Asia and the Caucasus is expected to grow sixfold in 2022 compared to 2021, to 3.2 million metric tons.

- On May 10, Finnish company Nurminen Logistics started running a container train from China to Central Europe using the Trans-Caspian route.

- Also in early May, railway experts from Georgia’s state railway met in Ankara with counterparts from Turkey, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan to discuss further the Middle Corridor project.

- Georgia is working with businesses from Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan to develop a new shipping route employing feeder vessels between Georgia’s Poti and Romania’s Constanta ports.

- The TITR currently has only about 5% of the Russian route’s capacity, but Central Asian countries have been spending heavily to develop modern infrastructure.

- For example, Kazakhstan invested approximately $35 billion over the last 15 years to build more than 2,000 kilometers of railways, 19,500 kilometers of roads, 15 airports and port capacities along the Caspian Sea.

- In 2022, Kazakhstan announced a $20 billion investment package for diversifying transit and freight transport routes and integrating logistic solutions.

- The EU is Kazakhstan’s most significant trade partner, representing 40% of its external trade and an important supporter of regional development in Central Asia.

- Currently, Kazakhstan’s exports to the EU consist almost entirely of energy and raw materials.

Source: TITR Association, Caucasus Watch

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is that the Middle Corridor will continue to develop as an economic region with increasing interest and support from the U.S. and the EU. These two partners see the potential for increasing the resilience of supply chains and energy supplies. In addition, both will seek strategic benefits in a more stable and prosperous region, buffering the global competition with China, Iran and Russia.

Russia’s soft power

Since these three powers are overstretched strategically, and the corridor is unlikely to be used to isolate or contain any of them, they will most probably opt for cooperation and acceptance rather than competition.

That said, there is every expectation that Russia, China and Iran will continue to apply soft power and “gray zone” tactics to influence the political alignment of the region to their advantage. Kazakhstan, for instance, will likely remain highly susceptible to Russian pressure, and Moscow will continue to use its partnership with Armenia to sway Azerbaijani policy.

However, stable, effective and focused local governments that are willing and able to cooperate could significantly influence the paths of regional progress.

The wild cards

Kazakhstan and Georgia are among the wild cards. Another is global inflation and recession, which could significantly diminish the need for the Middle Corridor as a logistics route. Still another potential factor is the Three Seas Initiative in Central Europe, a public-private infrastructure development body that looks to extend beyond EU-member states. It could bridge projects across the Caspian Sea if it manages to grow to a “four seas” initiative.

Finally, there is the issue of climate policy, which affects oil and gas development. Hydrocarbons are crucial to generating the prosperity needed to advance national and regional development in the region. The war against Ukraine, the energy crisis and spiraling prices in Europe have prompted reconsideration and moderation of some of the most aggressive anti-fossil fuel policies. The region could be adversely affected if policies return to a more strident form.