Shifting winds in the Far East

Challenged by China, Washington is scrambling to defend its Pax Americana by shifting trade policies and diluting commitments to provide security to American allies overseas – such as Japan. Now the country faces limited options and risky policy choices.

In a nutshell

- China is a ‘wounded civilization’ that is prone to steamrolling neighbors

- For most Asian nations, Washington’s new trade and defense policies are not helpful

- U.S. ally Japan faces a particularly large set of economic and security policy dilemmas

The geopolitical dynamics of East Asia are in turmoil due to China’s seemingly relentless rise and to the fading away of the Pax Americana in the region. Both these processes are unfolding and the outcome remains highly uncertain. Amid this volatile situation, the relationship between the People’s Republic of China and Japan is often fraught and complex.

China’s shadow

Like most other Asian nations, Japan is faced with Beijing’s attempts at establishing China as Asia’s hegemon. For the time being, the Chinese leadership is not averse to ratcheting up the tension. At present, China has strained relations with India and most Southeast Asian nations, in addition to tension with the United States.

It was always expected that, following China’s historic rise to the second largest (and possibly soon the largest) economy in the world, geopolitical or even military friction would eventually erupt between the two states. This has been in the nature of emerging and fading hegemonic powers since times immemorial.

Chinese President and Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping has a more forceful personality than his two predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin. However, the rise in Chinese self-confidence noted during the past decade would have occurred regardless of who took power in Beijing.

The geopolitical dynamics in East Asia are further complicated by the unpredictability of the U.S.

China is a “wounded civilization.” The humiliations and devastation the Middle Kingdom suffered in the 19th and the 20th centuries are not forgotten among its people and, especially, the ruling elite. It is doubtful that the growing assertiveness China shows toward its neighbors is a deflection from internal difficulties such as the Covid-19 pandemic or the tensions caused by the gradual slowdown in the Chinese economy. Beijing’s posture is simply part and parcel of the shifting dynamics in East Asia and the wider geopolitical landscape.

From the perspective of East Asia, the geopolitical dynamics are further complicated by the unpredictability of the U.S. under President Donald Trump. Washington’s allies feel they cannot rely on American support in case of crisis. This mainly results from Mr. Trump’s volatility when dealing with President Xi.

The American umbrella

There can be no doubt that Japan, like many European NATO members, agrees with President Trump when he complains about allies not contributing their full financial due to the common defense. When it comes to the monetary aspect, Japan’s position might not be quite as weak as that of leading European NATO members. However, in Japan’s case, it is the prevailing security mentality that attracts justified U.S. criticism. For too long, Japan has taken for granted that the American ally provides the nuclear and conventional weapons umbrella. At the same time, Tokyo uses its constitutional constraints as an excuse for not assisting the U.S. in its overseas military engagements.

Under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, relations somewhat improved, but the stubborn, substantial American deficit in bilateral trade leaves enough substance to Washington’s complaint that Japan has been what it calls a “freeloader.” The situation saddles Japan with two major challenges. First, Tokyo must find reliable partners and allies beyond the U.S. Second, it must stabilize its modus vivendi with the Chinese.

Facts & figures

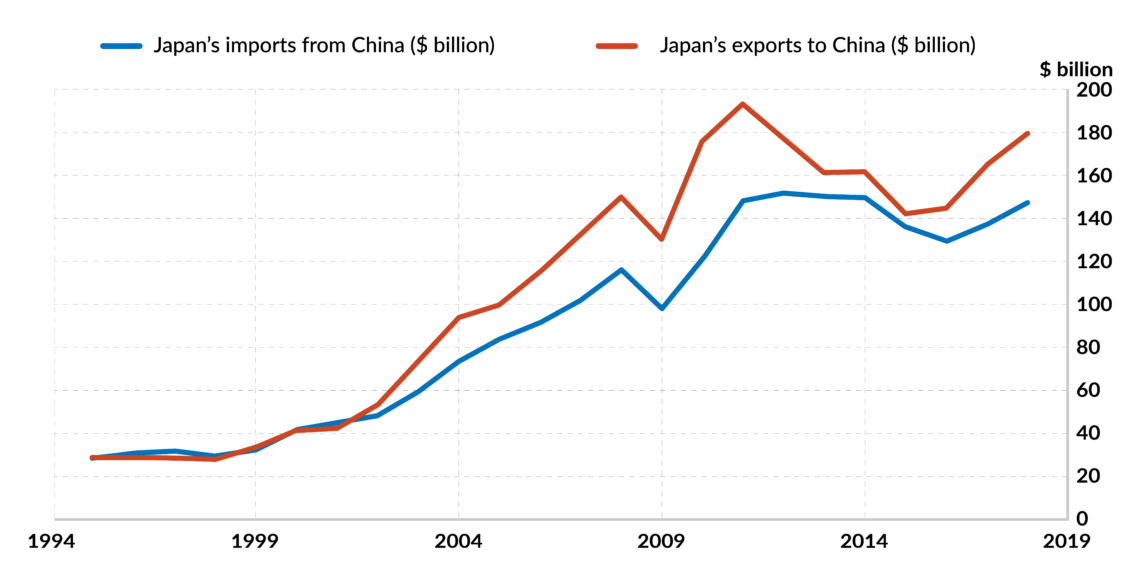

Japan’s current position toward China is wrought with ambiguity. On the one hand, stable economic relations between the two countries are desirable. Japan strongly depends on supply chains that include China. China is Japan’s second-largest trading partner after the U.S., and Japan is China’s third trading partner after the U.S. and Hong Kong.

On the other hand, Tokyo would like to reduce its economic dependence on China. However, this will remain difficult to accomplish as long as India’s economy does not live up to its potential and question marks continue to hang over U.S. trade policies.

East China Sea quarrels

Then, there are the shadows of past and present disputes between China and Japan. Most troubling is the situation around the Senkaku Islands (in Chinese, Diaoyu Islands) in the East China Sea. Since the spring of 2020, there have been unusually frequent incursions of Chinese military aircraft into the Senkaku Islands’ airspace. Simultaneously, Chinese fishing boats have entered the territorial waters around these uninhabited islands. The area has abundant fisheries and it is suspected to harbor valuable raw materials below the seabed.

There is a constant threat that things might slip out of control, by design or accident.

The Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands are contested between Japan, the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan). Historically, China has a strong claim. During the imperial Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the Senkaku Islands were Chinese and have been shown as such on ancient maps. Then, in 1895, Taiwan became a Japanese colony (after China’s defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895).

After the World War II capitulation of Japan in 1945, Taiwan returned to the Chinese Republic of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. The U.S. occupied Japan until its sovereignty was restored in 1953, under the Treaty of San Francisco. However, Okinawa and the Senkaku Islands remained under American administration until 1972, when they were returned to Japan.

Rightfully, the Senkaku Islands should have been returned to Taiwan. Needless to say, Beijing has never recognized Japan’s sovereignty over these islands and backed up its position not only with written protests but also with incursions into their territorial waters and airspace.

There is a constant threat that things might slip out of control, either by design or by accident. If a Chinese surveillance aircraft is brought down by a Japanese fighter aircraft defending the Senkaku Islands’ airspace, things could easily descend into open conflict. Furthermore, there is room for escalation.

China has also laid claim to the Okinawa archipelago, where one of the most vital American overseas bases is located. Today, China’s nationalists’ leading voice, the “Global Times” tabloid newspaper, gives prominent support to the Chinese claims for Okinawa.

President Xi’s visit

Before the Covid-19 outbreak, the Chinese leader was supposed to visit Japan in April 2020. The pandemic made this impossible and no new date has been set up. In the meantime, the Chinese intervention into Hong Kong’s security legislation prompted many in Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party and the opposition to demand the event be canceled for good.

Visits of Chinese leaders in Japan are highly political affairs. The last official call by a Chinese president (at the time it was Hu Jintao) took place in 2008. Before that, Jiang Zemin came to Tokyo in 1998. Significantly, President Xi did not pay a visit to Japan during his first term in office (2013 to 2018).

Tokyo will be attempting to ease its economy’s dependence on China.

When and if President Xi visits will carry a great significance for the short-term evolution of Sino-Japanese relations. Undoubtedly, a large part of the Japanese industrial and foreign policy establishment does not want to upset the slight improvement in bilateral relations. Diplomatic circles in Tokyo think the Chinese leader will eventually come. Some see November as an opportune moment. Of course, the coronavirus outbreak will continue to affect the timetable.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario for the coming months is that the management of bilateral relations will be ambiguous or even duplicitous. There will be a tendency in Beijing and Tokyo to keep a steady course that enables a favorable climate for economic exchange. While U.S. policies for the Far East remain volatile, neither Beijing nor Tokyo has an interest in far-reaching geostrategic shifts – at least not before the outcome of the November presidential elections is known.

Diversification

All the same, Tokyo will be attempting to ease its economy’s dependence on the Middle Kingdom. A step in this direction was establishing a fund that assists Japanese companies in moving out of China. Significantly, this support is not only provided to companies repatriating production facilities to Japan but also to companies that relocate to third countries.

For some time, Japan has substantially increased its economic footprint in India and in Southeast Asia. This move is welcomed by the countries concerned. It provides a much-needed counterweight to the increasing economic and geopolitical reach of China, not least to its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

However, a degree of skepticism is warranted here. During the past months, both before and during Covid-19, Tokyo and Beijing were on good terms. The Chinese praised Japan for the assistance provided during the coronavirus crisis. In turn, Tokyo abstained from blaming China for spreading the virus – to the disappointment of the Trump administration. At the same time, however, China increased its military aircraft forays into the Senkaku Islands’ airspace.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has contributed to the improved relations. However, the end of his exceptionally long term of office is nearing and it is uncertain what position on China his successor may adopt. Tokyo’s reaction to the heavy-handed Chinese interference in Hong Kong’s rule of law has been restrained. There is a lot at stake for Japanese companies in the former British colony. Japanese business was not at all pleased by the continuous street protests there. Eventually, Japan will have to come to terms with Hong Kong being fully part of the People’s Republic.

New partners

The most likely scenario for Japan’s security policy in the years and decades ahead is the strengthening of ties with other Asian nations that could stem China’s expansion. While there might have been hopes that China’s rise would be peaceful, the growing concern today is that Beijing has opted for an expansionist course.

Under these circumstances, the search for possible allies and partners becomes more urgent. Tokyo has enhanced its security cooperation in the “Quad,” an informal Quadrilateral Security Dialogue consisting of Japan, Australia, India and the United States. Further options of security cooperation within Asia will be explored, particularly in the South China Sea.

The Indo-Pacific has emerged as one of the leading security theaters of the 21st century. For Tokyo, the main challenge in the new geopolitical chess game will be to keep relations with Beijing stable, even as Japan expands its military strength and regional security cooperation to try to contain Chinese hegemonic aspirations.