How the EU may respond to a new sovereign debt crisis

If rising borrowing costs push some eurozone countries to the brink of another sovereign debt crisis, a simple repetition of harsh austerity measures is not in the cards.

In a nutshell

- Easy money and lavish public spending failed to fix the EU’s growth problem

- Now, inflation may lead to a sovereign debt crisis in overextended countries

- The ECB and EU governments will try to avoid austerity measures

Rising interest rates are beginning to awaken concerns about debt sustainability in several overextended eurozone nations. Steering them away from a fatal path may soon become the European Union’s next big challenge.

However, a remake of harsh austerity measures implemented in Greece and some other EU countries during the previous decade’s financial and sovereign debt crises will not happen, given the undeniable failure of these policies. What remains possible is a “hybrid” approach that could combine the eurozone’s further monetary tightening with even looser fiscal policies by member governments.

From a free lunch to public debt

In early 2015, the European Central Bank (ECB) launched its first large-scale quantitative easing (QE) programs. Ever since, the euro area economy has been drowning in cheap money. Moreover, interest rates stayed near zero for years. Between September 2019 and July 2022, they even went negative – clearly, a debt-friendly context.

Back then, the vertiginous rise of debt was not a concern for the ECB; its priority was to combat critically low inflation. Strangely enough, despite trillions of euros pumped over time into the eurozone, the central bank’s 2 percent inflation target remained out of reach.

When the pandemic hit in March 2020, forcing governments to lock down their economies, inflation fell even lower. As the specter of deflation was looming, policymakers and economists urged governments worldwide to “spend as much as they can … and then spend a little bit more.” Eurozone governments took the advice quite literally. Many let their debts and deficits balloon to unseen levels – substantially higher than those observed during the 2010s when a systemic sovereign debt crisis had threatened to destroy the euro.

Scenarios for Georgieva’s leadership of the IMF

And yet, elite economists, mainly those close to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), insisted that “we must think differently about the sustainability of public debt.” As long as growth rates exceed interest rates, governments should not worry about debt too much, the argument went.

Undeniably, a more lenient attitude toward debt helped mitigate the real economy’s damage caused by the pandemic. However, to some particularly spendthrift governments, the IMF’s famous “spend, spend, spend” motto may have sounded like an invitation to take on ever more irresponsible debt.

Governments had been reassured that they could count on the ECB as a lender of last resort if their debt came under pressure on sovereign bond markets. And indeed, early in the health crisis, the ECB had acquired the habit of buying the debt notably of southern eurozone states. As a result, its total asset curve rose sharply, peaking at nearly 8.9 trillion euros in July 2022. Still, inflation did not pick up – until it did, and 2022 finally became a wake-up year to reality.

Sovereign debt specter returns

By late 2021, a rising inflation trend was perceptible in the eurozone. A few months later, it would hit double-digits. Also, it turned out to be persistent, not transitory (i.e., pandemic-related), as the ECB had pretended for over a year. And then, on February 24, 2022, the Ukraine war took the world by surprise.

The war exacerbated Europe’s emerging inflation problem by creating an unprecedented energy shock. The timid post-pandemic recovery was wiped out within weeks, and a new recession was looming. Globalization was in retreat. Europe found itself in a perfect storm of adverse, deeply entangled geopolitical and macroeconomic factors. In this exceptional context, eurozone governments continued on their path of fiscal activism, this time to help households (and, to a lesser extent, firms) get through the energy crisis.

The doom loop

However, the threat of stagflation forced the ECB to change course and tighten its monetary policy. Between July 2022 and February 2023, it proceeded to six interest rate hikes, pushing borrowing costs to the highest levels since late 2008. Moreover, asset purchase programs were closed, leading to a progressive slimming of the ECB’s balance sheet. By January 2023, its total assets had already fallen to 7.894 trillion euros (from the peak of 8.828 trillion euros in July 2022).

The time seems ripe for closer attention to public debt and deficits. In a setting of low (possibly negative) growth perspectives, rising interest rates generate concerns about debt sustainability in several eurozone nations. Steering those countries away from disastrous debt paths might soon become the EU’s next big challenge.

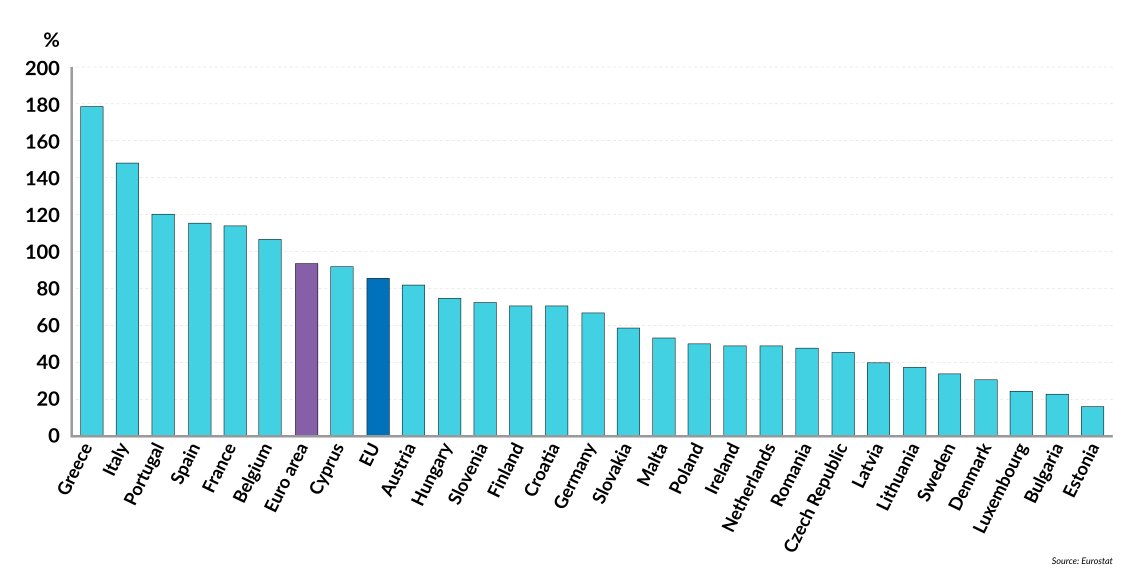

Facts & figures

Government debt at the end of the third quarter 2022

‘Austerity’ as a dirty word

The word “austerity” had been banished from European policymakers’ vocabulary long ago. Apparently, too many negative or punitive connotations can be associated with the term for it to still fit in the policy toolkit of a modern welfare state.

The United Kingdom, a former EU member state, recently broke the taboo by announcing significant tax hikes for the upcoming months, combined with no less drastic public spending cuts. Facing the consequences of years of excessive fiscal spending and a monetary policy running out of options, the EU may be tempted to follow Britain’s lead.

The pending reform of the bloc’s common fiscal rules for limiting public debt and deficits, grouped under the Stability and Growth Pact, suspended at the pandemic’s outbreak and not reinstated yet, could become the occasion to revive long-abandoned debates.

Reportedly, some voices in European policy circles already call for a return to the hardline austerity policies adopted in the EU during the financial and sovereign debt crises a decade ago. However, it is unlikely that these appeals will be heeded: the blatant failure of the austerity experiments conducted in the early 2010s is still vivid in policymakers’ minds.

The damaging rescue

In those turbulent years, to fend off a devastating euro crisis, European heads of government had agreed to bail out those standing closest to the precipice: Greece, Cyprus, Ireland and Portugal. A credit line was granted to Spain. In return, the beneficiary countries had to comply with highly stringent conditions, notably the structural reforms they were asked to carry out at home. “Cut as much as you can” was the leading motto back then.

Is the European Central Bank still in control?

The idea was that drastic reductions could be applied virtually to everything in the concerned nations’ economies – from the number of public companies to the salaries of public employees and all kinds of government services, including in critical infrastructure sectors such as healthcare and education. Bonuses, overpay, and pensions had to be capped, while the age of retirement needed to go up. Labor markets had to be reformed, and government hiring largely adjourned.

Existing taxes were to be increased substantially, and new ones were invented. The targeted member states also needed to rebuild their administrative capacity to collect and spend funds more efficiently. Some had overly complicated and ineffective tax collection systems that favored tax evasion, corruption and the development of large informal sectors. In some cases, entire institutional and regulatory frameworks had to be revised.

Many of the required reforms made sense. After years of profligate public spending (before and after the 2008 financial crisis), these countries had amassed structural deficits so colossal that many eurozone leaders believed outside coercion was the best way to bring their finances into order.

Oxymoronic policy

At the time, the bet was that the painful efforts and sacrifices would inspire “business-boosting confidence” among foreign investors. Hence, economic growth would be at the end of the tunnel for the eurozone’s problem children. That assumption was at the heart of a policy model optimistically named “expansionary austerity.”

Alas, the plan backfired badly on the nations under duress. Investors largely stayed away, and companies went bankrupt in droves. Unemployment exploded, and productive capacities declined. Growth was fading. Public debt-to-GDP ratios and, with them, the risk of sovereign default did not necessarily decrease. Social unrest was brewing, giving rise to anti-European sentiments. A profound divide between the eurozone’s north and south emerged, and the bloc’s already fragile cohesion was at risk of a breakdown.

According to some critics, the bailout programs implemented in the 2010s were not even lawful. The terms had been so severe that their application pushed several countries into a fiscal trap from which some have yet to fully emerge.

The spiral of economic contraction (some referred to it as “austerity on steroids”) forced upon societies not only deepened their depression and delayed economic recovery but pushed large parts of populations to the brink of poverty. Notably, Greece was driven into a genuine humanitarian emergency.

Groping for creative solutions

Overall, these “austericidal” policies had disastrous economic and political consequences that continue to haunt Europe up to the present day. In hindsight, many asked: How could seasoned policymakers fall prey to what American economist Paul Krugman called the “austerity delusion”? How could they reasonably believe that growth would come back after desperate and indebted governments were compelled to impose on their already depressed economies the strictest fiscal austerity measures ever seen in the economic and monetary union?

Today, EU policymakers face a nasty dilemma. Hardline austerity was a failure, a remake is not an option. But the opposite stance, aggressive fiscal stimulus, has reached its limits too.

The political corruption of monetary policy

An option to consider: selective austerity

Some economists predict a “regime shift” that marks a rupture between monetary and fiscal policies. The ECB’s monetary policy may shift toward ever more tightening to fight inflation, while member states’ fiscal policies might become ever looser. Budgetary spending is already exploding in sectors such as healthcare, defense, and the green and digital transitions. Big government is here to stay.

Beyond an emerging conflict between monetary and fiscal policies, there are hints supporting even more hybrid scenarios.

For example, in July 2022, the ECB adopted an emergency QE program dubbed the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). Even in the current context of quantitative tightening, this new monetary policy tool will allow the ECB to implement selective QE by purchasing all the new debt issued by eurozone countries in distress.

In a way, TPI is a bailout mechanism in all but name, except that (unlike what was going on during the 2010s austerity era) very few conditions are attached for countries to benefit from it. Even though it has not been put into practice yet, the newly created rescue program has been criticized for incentivizing fiscally fragile governments to continue assuming more and more excessive debt without engaging in serious structural reforms.

As part of an ideological road map, selective austerity might become a way to fine-tune redistribution within European welfare states. But it can also backfire.

EU policymakers seem aware of the problem. The European Commission is currently exerting pressure on precisely those governments whose debt-to-GDP ratios are excessively high, urging them to implement cost-containment measures, notably in pensions.

Spain is a case in point. By now, the national social security fund is well shy of being able to cover the payment of pensions. In 2022, over 224 billion euros was needed, but only 152 billion euros was available. Year after year, the difference is financed by public debt. Currently, Spain’s public debt-to-GDP ratio stands at an explosive 115 percent. According to forecasts, if nothing changes, it could balloon to 191 percent by 2050.

Three reform options are currently being discussed: decreasing pension amounts, raising the retirement age and increasing mandatory contributions to the system. So far, no consensus is in sight for any of them, much to the discontent of Brussels. France, too, is committed to conducting an ambitious pension reform needed to restore the state’s fiscal balance. And that is supposed to be accomplished in a climate of social unrest.

If a government forces people to work longer and then pays them lower pensions, this can be seen as a selective austerity measure, as a particular group in society is affected. In contrast, other (discretionarily designed) groups are granted tax credits or specific welfare cheques – austerity for some, stimulus for others.

As part of an ideological road map, selective austerity might become a way to fine-tune redistribution within European welfare states. But it can also backfire. The current pension reforms do not consider the demand contraction to which they can lead after an increasingly large part of the population sees their purchasing power melt away.

Especially in European consumption-driven economies, this could adversely impact growth and, once again, affect the sustainability of public finances. The fact is that policies that consist of pressing the brake and accelerator at the same time are likely to create many new challenges for the eurozone’s future.