The euro area could be at risk of a new sovereign debt crisis

The eurozone’s debt is starting to haunt European Central Bank’s policymakers and leaders who recklessly increased public spending.

In a nutshell

- The eurozone finds itself in a precarious situation due to interlocking global crises

- Excessive sovereign debt puts some countries and the common currency at risk

- Central bankers hope an “anti-fragmentation instrument” will preserve the system

Between 2009 and 2012, the euro area experienced a full-blown sovereign debt crisis that threatened to tear the monetary union apart.

At the time, problems came to a head when lenders in European financial markets lost faith in the fiscal sustainability of several member states and started demanding higher risk premia. As they were confronted with soaring borrowing costs, the affected sovereigns quickly found themselves unable to repay the debts they had built up during the Great Recession in the late 2000s. Eventually, investors’ biggest fears were close to becoming self-fulfilling prophecies. A downward spiral pushed Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Cyprus to the brink of euro exit. Domino effects between Europe’s so-called periphery and core put Spain, Italy, Belgium and France at risk as well.

One of the first policymakers to understand the risk to the common currency itself was Mario Draghi, then-president of the European Central Bank (ECB). He was the one who, in extremis, had ended the debacle by committing, during his memorable July 26, 2012, speech, to do “whatever it takes” to stabilize sovereign bond markets. Three words that saved the euro, it is often said.

Could such a frightening scenario repeat itself today, now that the eurozone has woken up to new major global threats, ranging from post-pandemic stagflation to a looming world war?

Central bankers and policymakers tend to present a reassuring picture of Europe’s present-day sovereign risk situation. However, significant challenges remain.

Debt overhangs

First, public finances are in a worse state today than at the peak of the previous sovereign debt crisis. For instance, Greece’s government debt-to-GDP ratio, which stood at 127 percent in 2009, ballooned to 211 percent in 2020. After the pandemic hit, the proportions for Spain and Italy climbed to 120 and 155 percent respectively. Public debt amounts are impressive, too. In June this year, Italy’s debt mountain reached 2.88 trillion euros. By comparison, back in 2009, Greek’s debt of 300 billion euros was enough to trigger panic among sovereign bond investors.

Current trends suggest that governments’ funding needs might even increase in the months or years to come. The health crisis, which left lasting scars on economies and public finances, is not over. More recently, long underestimated geopolitical risks resurfaced at Europe’s borders. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted the European Union to make costly decisions regarding sanctions, defense, refugee reception and alternatives to Russian energy. Finally, Europe’s lofty climate ambitions will be extremely expensive.

The sovereign bond yield spreads between peripheral and core member states widened dangerously.

Energy, food and other prices trending upward on all fronts could make it hard for some member states to avoid another recession over the next few months – unless they respond with more deficit spending. Luckily for such countries, the EU’s fiscal rules will be kept on ice until at least 2023. For some countries, the fact that no borrowing limits have been in place for several years is incentive enough to continue on the course of ever-larger government spending and debt.

Centrifugal forces

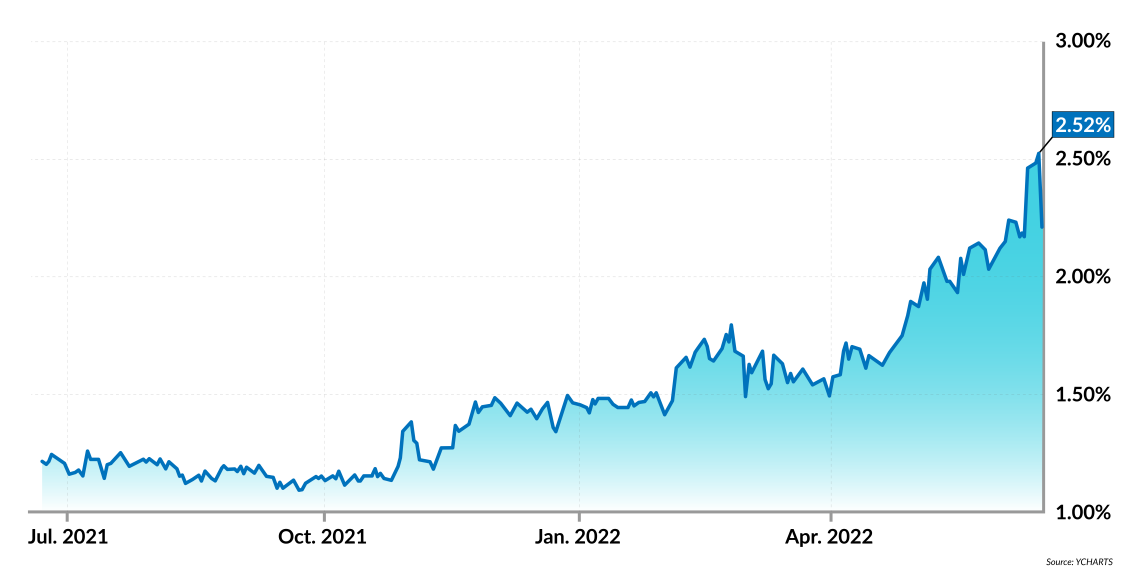

The second challenge involves borrowing costs for eurozone governments. In early spring 2022, after years of relative stability, interest rates that markets required of governments for repayment of outstanding public debt surged several times to multiyear highs before falling just as sharply a few days later. It is noteworthy that, during these short episodes, the sovereign bond yield spreads between peripheral and core member states widened dangerously. The spreads between Italian and German 10-year bond yields, often used to gauge investors’ fear/confidence, reached 2.52 percentage points on June 14.

Facts & figures

Italy-Germany 10-year bond spread

On March 12, 2020, at the coronavirus pandemic outbreak, there was another such “self-fulfilling cross-border flight-to-safety” episode, but of much greater amplitude. It occurred after ECB President Christine Lagarde had bluntly stated that her institution was not there to “close spreads.”

The turmoil in financial markets makes clear that what the economists Ignazio Angeloni and Daniel Gros labeled “the centrifugal forces between core and peripheral countries” can flare up at any moment and put the cohesion of the currency union at risk. This danger is due to a fundamental design failure of the eurozone that has never been overcome.

In May 2022, markets eventually calmed down, but observers agree that southern European sovereign bonds remain vulnerable to fire sales. More so as some nations, such as Greece, Italy and Spain, remain heavily exposed to the infamous “sovereign-bank doom-loop” risk. This negative spiral, by which one protagonist can drag down the other, was at the heart of the previous debt crisis. Back then, two scenarios interacted. On one side, overindebted governments pushed over the cliff banks that held too many of their bonds. On the other, ailing banks could take down the governments that tried to rescue them.

Today, banks’ so-called “home bias,” i.e., their propensity to pile up domestic sovereign bonds, seems stronger than ever. Moreover, as Mr. Angeloni pointed out elsewhere, the “real condition” of the financial system in certain at-risk countries may come to light soon. Indeed, during the health crisis, the banking sector’s inherent vulnerabilities were temporarily hidden under a “protective blanket” that Covid-19 debt moratoria and public guarantees had laid on banks. “The burden on bank balance sheets will be greater in countries that face more demanding reforms, due to their structural backwardness, and which still have unresolved banking problems,” Mr. Angeloni wrote.

How to avoid a replay of adverse feedback loops between banks and public finances? Here indeed lies one of the main difficulties for the euro area today. Despite 10-year efforts and endless discussions between the EU and member states, the long-awaited Banking Union has still not been completed. Also, regrettably, cooperation with and among fiscal authorities leaves much to be desired.

Rising debt costs

About a year ago, another looming challenge appeared on the horizon: inflation. On the one hand, persistent inflation benefits governments, as it erodes their debt over time. On the other hand, it leads lenders to demand bigger risk premia from highly indebted nations. For this reason alone, the borrowing costs of these nations will now rise inexorably.

These rate hikes will make borrowing more expensive. Combined with declining growth, they could negatively affect sovereign debt sustainability.

The situation could quickly get tricky, as the ECB recently announced that it would tighten its monetary policy to keep inflation at bay. In May 2022, eurozone inflation rose to 8.1 percent, which is four times above the ECB’s 2 percent target. Even the most dovish among the ECB’s Governing Council members currently call for action.

In a statement of June 20, 2022, ECB President Lagarde confirmed that the first rise in short-term interest rates can be expected in July. One or two more rises of 25-basis points each might follow later this year. The ECB’s deposit facility rate has been negative since 2014 and currently it stands at -0.5 percent. Most market analysts predict it could reach +0.25 percent by 2023. For Robert Holzmann, one of the Governing Council’s hawks, this should happen already this year. Of course, these rate hikes will make borrowing more expensive. Combined with declining growth, they could negatively affect sovereign debt sustainability.

Moreover, the ECB is going to substantially lower its bond buying throughout 2022, at least compared to 2020 and 2021. As expected, net purchases under its 1.85 trillion-euro Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) ended in March 2022. After an early June meeting, the Governing Council announced in a surprise move that net purchases under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) will also end as of July 1, 2022. The perspective that there might soon be less monetary support to southern European debt nations could also contribute to reviving investors’ angst.

In essence, a reduction in net purchases means that the ECB will stop buying all the new debt issued by eurozone governments. According to an analyst consulted by The Financial Times, the central bank will buy less than 40 percent of it this year, down from over 120 percent during the pandemic’s peak. Another commentator, a former IMF deputy director and private sector economic strategist, wondered what would happen if the ECB ceased to be a major buyer of Italian government bonds. Who was going to help the country raise the additional hundreds of billions of euros it will need next year to cover its gross borrowing needs, the commentator wanted to know.

What appears to worry observers most is the next Italian general election, due to be held before summer 2023. Many are concerned that if Italy’s Prime Minister Mario Draghi were to leave the government, the country could plunge back into its politically chaotic past. Since February 13, 2021, when the 74-year-old former ECB head took charge, Italy has been enjoying a period of stability unseen for a long time despite its deep-rooted problems. With Mr. Draghi at the helm, investors seem to have improved, at least temporarily, their perception of the government’s creditworthiness. With his departure, their trust could vanish anew.

Narrow path

Over the coming months, the ECB will have to navigate a narrow path between continuing to support bond markets (through quantitative easing) and gradually withdrawing monetary accommodation to fight inflation (through quantitative tightening). Regardless of how this dilemma will be dealt with, the future will be challenging for the central bank.

The time when three simple words uttered by the ECB’s president were enough to stabilize markets in turmoil is long gone. According to Mr. Angeloni, a member of the ECB’s Supervisory Board during the Draghi era, Mr. Draghi’s whatever-it-takes statement was an emergency response applied to very particular conditions. Today, it just will not do to repeat it over and over again.

For years, the ECB’s leadership frequently used the famous phrase as a pledge or a reassuring promise in times of market disturbance. But to have any effect, it needed to be backed up by ever-larger stimulus packages to ensure that credit in the eurozone remained cheap. Put differently, ever more needed to be done to achieve ever less. A year before the pandemic hit and long before anyone thought of a comeback of inflation, OECD secretary-general Angel Gurria warned that the central banks “have run out of ammunition.”

‘Flexibility’ has become the magic word, allowing the ECB to continue to cap spreads on well-chosen eurozone sovereigns.

Nonetheless, according to a global financial data provider, the management of the assets in the ECB’s colossal balance sheet and, most notably, the reinvestments of long-term government bonds purchased under the APP and PEPP, are important options left. They will still help the central bank keep bond spreads as low as possible over a long period.

Unlike for APP reinvestments, the ECB is not bound by capital keys (i.e., market neutrality principles) when reinvesting PEPP proceeds. In a press conference on December 16, 2021, Ms. Lagarde suggested that “under stressed conditions,” her institution can freely decide when, where and how to reinvest them. “Flexibility” has become the magic word, allowing the ECB to continue to cap spreads on well-chosen eurozone sovereigns.

Wonder-weapon needed

In recent months, there has been increasing talk about a mysterious new policy instrument that could be adopted in case yield spreads started widening again after the ECB has made its first-rate hikes. The purpose would be to actively support debt-ridden governments when they face sharply rising borrowing costs due to tighter monetary policy.

Here again, one may wonder whether this would not be some European-style yield-curve-control that does not say its name. The practice of yield-curve-control is forbidden by EU Treaties, as it amounts to a hidden form of deficit financing or debt monetization. Ultimately, this leads to central bank complacency and fiscal dominance.

For the moment, the adoption of such a new tool has not been confirmed officially. Nonetheless, President Lagarde said in her June statement that a proposal for an “anti-fragmentation instrument” could soon be put forward for consideration by the Governing Council. The very fact that it is under discussion should be proof enough that there still is a systemic sovereign debt risk in Europe today.