China’s export controls are set to backfire

Prices for microchips are likely to increase due to Beijing’s export restrictions on strategic materials. In the end, the strategy will disappoint China.

In a nutshell

- China has begun to respond in kind to Western high-tech sanctions

- It tries to leverage its near monopoly in exotic materials

- Restricting supplies will only briefly harm Western companies

China and the United States have been in a deepening technology trade confrontation since 2019. Washington has used various approaches to restrict or block altogether exports of critical technologies, especially advanced microchips, from the U.S. and other developed countries to China. Until now, Beijing has not responded with much discernible retaliation.

The exception was its listing of the U.S. company Micron Technology, a memory and data-storage solutions maker, in May 2023 as a “significant security risk.” However, in July, Beijing decided to change tack and began limiting the exports of China-produced strategic raw materials. This is bound to trigger a “shock resistance” reaction by Western countries.

China’s Ministry of Commerce has announced that as of August 1, 2023, Chinese chemical suppliers must apply for government licenses to export 38 products, including two materials critical for manufacturing semiconductors, gallium nitride (GaN) and germanium dioxide (GeO2). The export license applications must identify importers and end-users. Also, to specify how the materials will be utilized. Beijing does not rule out adding other materials to the licensing system, such as indium compounds, also employed in semiconductor production.

Timing and targeting of Beijing’s export controls

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Mao Ning insisted that China’s export controls are lawful and do not target any country. However, Wei Jianguo, vice president of China Center for International Economic Exchanges, argued publicly that the measure is weighty, well thought through by Beijing and sure to “not only panic some countries but … also hurt some countries.”

Mr. Wei emphasized that “this is just the beginning of China’s countermeasures, and there are many more means and types of sanctions that China can use. If the high-tech restrictions on China continue to escalate, China’s countermeasures will also escalate.”

Germanium and gallium do not naturally occur in the earth’s crest; they are by-products of refining other metals. The two materials have military and civilian applications.

The timing of the export curbs makes the target clear: it was announced very shortly before U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s Beijing visit to meet China’s new economic policy team and tame the spiraling tensions between the world’s two biggest economies. Meanwhile, the Dutch government said on June 30, 2023, that it would require ASML Holding, the world’s largest producer of chipmaking equipment, to apply for an export license for shipments of its Deep Ultraviolet (DUV) lithography systems that enables the manufacture of cutting-edge chips. The requirement will come into effect on September 1.

Before the Dutch ban, the Japanese government restricted the exports of 23 types of chip manufacturing equipment from July 23, 2023. Also, in March of the same year, the European Union introduced its Critical Raw Materials Act, which calls for securing the supply of rare minerals needed for green technologies, including gallium and germanium (both fall into the “strategic” category considered essential to the EU’s green and digital transformation).

Read more on China-West rivalry

China’s challenge to the West in 2021 and beyond

The growing importance of raw material supplies

Beijing does not like that policy. One day after China’s export curbs on chipmaking materials were published, it unilaterally postponed the visit of Josep Borrell, EU high representative for foreign affairs and security, initially planned for the following week.

China’s strategic rationale

Germanium and gallium do not naturally occur in the earth’s crust; they are by-products of refining other metals. Like semiconductors and microchips, the two materials have military and civilian applications. Germanium has a variety of uses, including in solar products and fiber optics. The metal is transparent to infrared radiation and can be used for military equipment, such as night vision goggles.

Gallium is also a key raw material to cutting-edge technologies. Gallium nitride is used to produce the latest-generation integrated circuits for power grids, electric vehicles and telecommunications base stations. Due to their ability to operate in high temperature and frequency environments, gallium nitride microwave RF chips are used in missiles, radar and electronic countermeasures designed to deceive radar detection.

A 2020 report by the Institute of Mineral Resources of the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences showed that the world’s total gallium reserves at about 230,000 tons, with China leading the world in gallium metal production, accounting for about 80 to 85 percent of the world’s total reserves. A 2016 statistic released by the U.S. Geological Survey has the world’s proven germanium holdings at only 8,600 tons, of which the U.S. accounted for 45 percent, followed by China, which accounted for 41 percent of global germanium reserves.

According to China’s customs data, in 2022, Japan, Germany and the Netherlands were the largest importers of Chinese gallium products. The leading importers of its germanium products were Japan, France, Germany and the U.S.

China’s near-monopoly position on germanium and gallium mirrors the case of rare earths. China became dominant in gallium in 2012 after flooding the virgin gallium market with an underpriced surplus. It is known for exporting state-subsidized processed minerals at a low cost that competitors in other countries, burdened with stiff environmental requirements, cannot match.

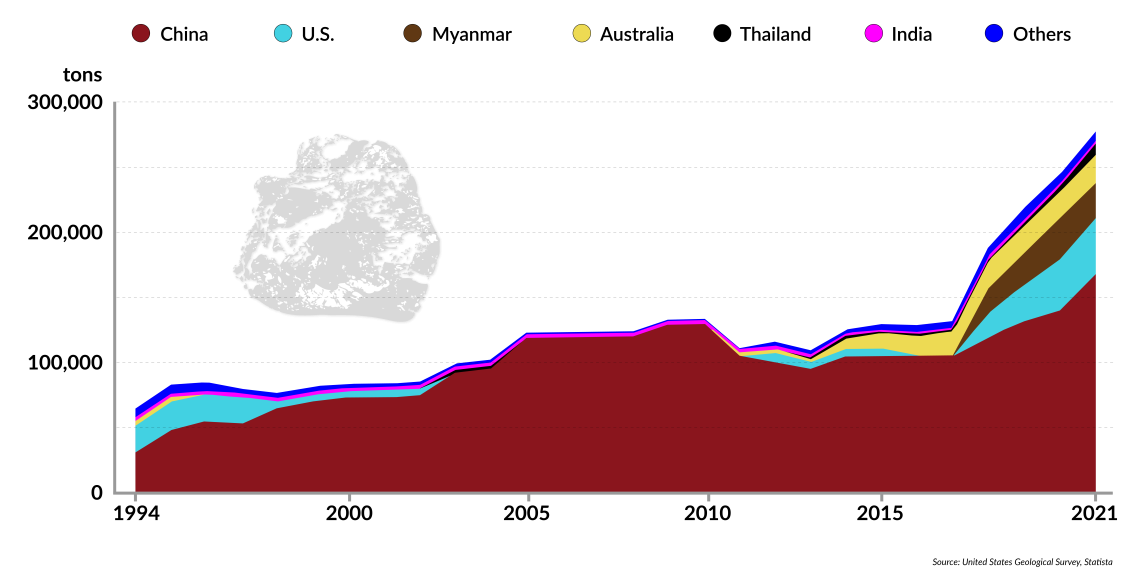

Over time, China has acquired the world’s largest aluminum oxide production capacity and gallium extraction technology. Today, it accounts for more than 95 percent and 67 percent of global production of gallium and germanium, respectively.

Facts & figures

Beijing twice tried to press Japan

China has a track record of using its dominant raw materials position in disputes with Japan. It restricted the rare earths exports in the 1990s to pressure Japanese companies, which were highly dependent on Chinese supplies. In 2010, China suspended rare earth exports to Japan in response to a collision between a Chinese fishing boat and a Japanese coast guard vessel near the Senkaku Islands (over which both sides claim sovereignty). China’s 2010 export controls triggered a search process for alternative supplies. Subsequent increases in rare earth elements production in Australia and the U.S. caused China’s share of global mineral production to dip from 98 percent in 2010 to 70 percent in 2022.

China’s dwindling rare earth monopoly

Other countries are also able to produce China-sanctioned materials. Belgium, Canada, Germany, Japan and Ukraine can all produce germanium. Japan, South Korea, Ukraine, Russia and Germany also make gallium. But only a few companies worldwide have acquired the capacity to produce gallium at the required purity. One is in Europe, and the rest are in Japan and China.

After more than 30 years of intensive globalization, the Western industrial countries have become used to leaving environmentally harmful tasks to China. And China took advantage of its large production and low cost to squeeze out foreign competition. For example, Germany stopped primary production of gallium in 2016, and Kazakhstan ended it in 2013. Such business decisions allowed China to establish its near monopoly.

At first glance, Chin’s approach to sanctioning the West is a tit-for-tat, but Beijing’s leaders have a longer-term design.

Today, according to the European economy’s Critical Raw Materials Coalition, China produces 60 percent of the world’s germanium and 80 percent of the world’s gallium. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Alliance (CRMA) confirms this.

Data from the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR) shows China as the supplier of 27 tons of gallium to Germany in 2022, accounting for 55 percent of Germany’s total imports, and 3 tons of germanium, accounting for 75 percent of total imports.

China’s intent behind the countermeasures

At first glance, China’s approach to sanctioning the West is a tit for tat, but Beijing’s leaders have a longer-term design. Their measure aims to raise the cost of manufacturing chips in Western countries, thereby creating time and space for Chinese companies to catch up in the crucial technological race. By restricting the export of its strategic raw materials, China can depress the profits of U.S., South Korean, Japanese and European chipmakers, thus weakening their competitiveness.

This approach also targets the Western countries’ military industries. According to the U.S. Department of Defense, the country has a strategic stockpile of germanium but is short on gallium reserves. As a result, China’s export controls could crimp the efficiency of U.S. military production.

Beijing expects this situation to persuade the bosses of Western multinationals to lean on their governments to roll back the trade restriction against China. Apple CEO Tim Cook, Tesla CEO Elon Musk, former Microsoft CEO Bill Gates and other big-wig U.S. business executives frequently flock to China. The ruling team of Xi Jinping reasons that since China is the world’s largest semiconductor market, with about one-third of global chip sales, many Western multinationals will want to discuss the wisdom of the chip bans with government leaders.

Scenarios

The success of China’s countermeasures depends on whether they achieve the abovementioned goals. Whether Beijing’s approach will help China’s semiconductor industry will be seen in four or five years. The trend does not look good, and Beijing’s leadership knows in their hearts that the U.S.-China relationship will not return to its halcyon days, at least not under President Xi Jinping’s rule.

What will Beijing’s new export rules achieve instead is convincing the West that it should get serious quickly about securing its own supply chain and rebuilding its once-strong domestic mining and refining industries.

Beijing’s move toward tit-for-tat trade sanctions will have some impact on the West in the short to medium term. Rises in raw materials prices are inevitable. No country can quickly replace supplies from China. A Chinese germanium producer revealed that they had received several inquiries from buyers in the U.S., Japan and Europe after Beijing’s export restrictions were announced, and demand for the product shot up overnight.

Even though Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) stated that, after evaluation, it did not expect “the restrictions on gallium and germanium, the raw materials, to have a direct impact on TSMC’s production,” an increase in the cost of the chips the world leader makes is also inevitable.

However, history shows that as China imposed export controls or sought to raise the prices of its strategic materials by limiting exports, it prompted importing countries to look for alternative suppliers or resume domestic production, inevitably restoring a measure of supplier competition. That happened in the case of rare earths. Beijing’s latest export restrictions will likely lead to the same outcome in a few years.